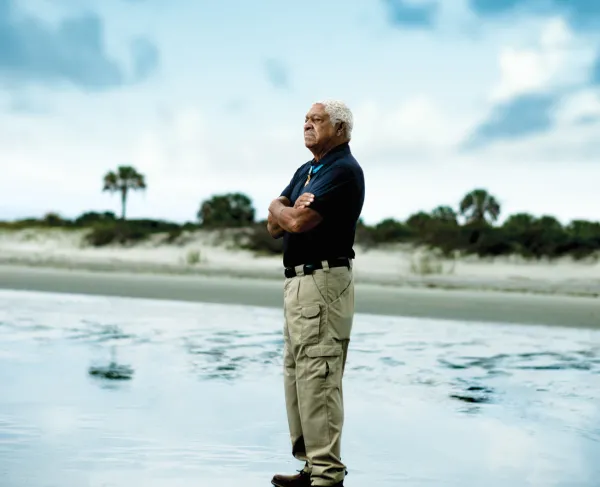

Medal of Honor Recipient Melvin Morris Visits Morris Island

Vietnam War Medal of Honor recipient Melvin Morris reflects on his connection to the first African American soldier to receive our nation’s highest honor.

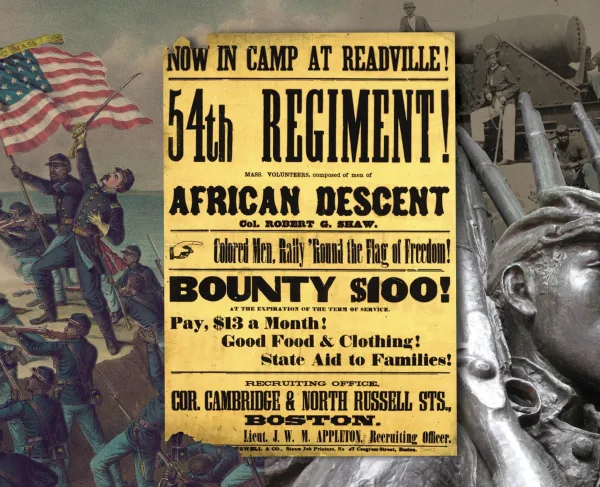

William Carney was born in 1840 as a slave. He managed escape with the Underground Railroad to Massachusetts and worked, made a life there. When he joined the 54th Massachusetts, he had a little education, so he was made a sergeant. William Carney must have felt that it was his duty to fight for the Union. In other words, “I have my freedom. But to ensure my freedom, I got to make sure that our country stays free. It is my honor to serve my country. My duty.”

It’s important for us to know that story because it shows the thought process of such men that “If we’re given the same rights and privileges, we’re willing to fight for our country. And we will fight hard.” That’s what he tried to prove. That’s what the 54th tried to prove. That alone was enough motivation for them to fight. Even though they were paid far less than the white soldiers, they got less clothing; they continued to march. They wanted to go into battle and win their freedom, and they performed there as best as any soldier could.

I come from Oklahoma, a place called Okmulgee, capital of the Creek Nation. There wasn’t much going on there in the ’50s, no work to speak of. My first was job was working at the bowling alley; I think I made 65 cents an hour. I said, “No, this isn’t going to cut it.” And my brother and I both went into the military, because the National Guard was recruiting minorities. I stayed there a year, and volunteered to go to the regular Army in 1960. I went Airborne and then volunteered for the Green Beret. That’s a two-year training, and you can fail out at any point.

When you walk point, you’re the lead man of a large element. You’re in the visual. You’re by yourself. You are actually what they call the spotter on the trail or the path. You have to be alert; if you fail and you get caught in an ambush, everybody gets killed. The most dangerous job in Vietnam was the point man.

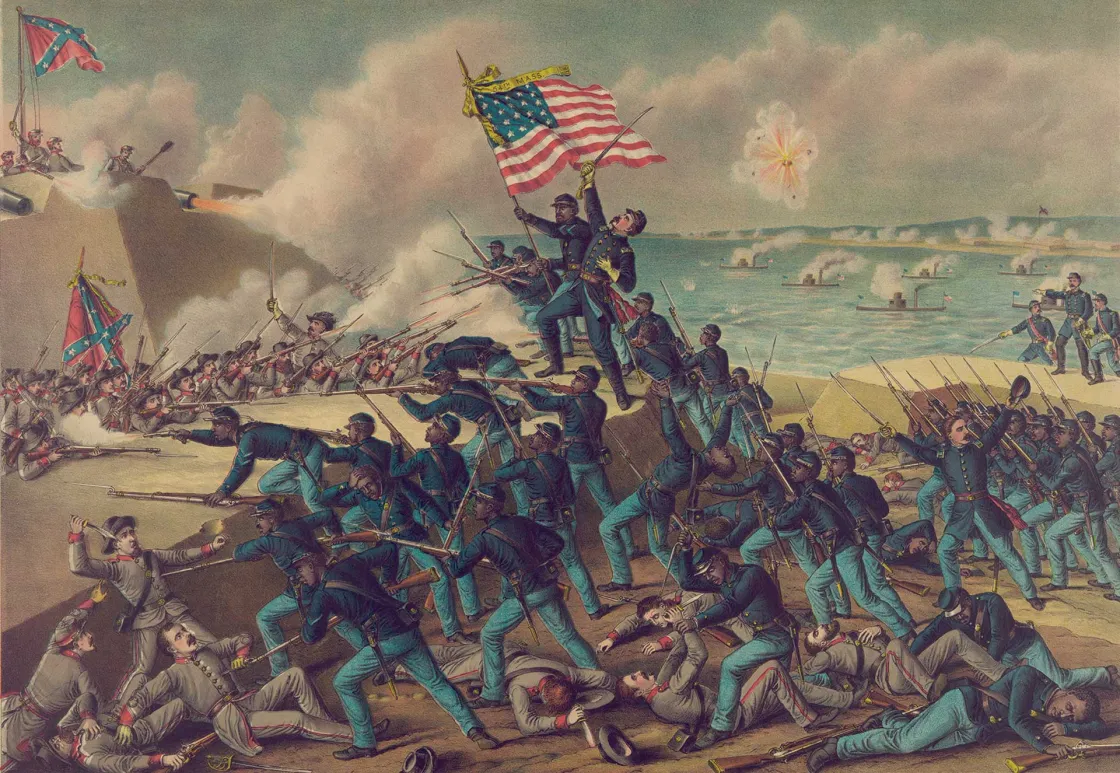

The most dangerous job in the Civil War, as I understand it, was the color bearer. He’s going to charge. He’s going to be upfront. He’s going to ignore everything around him. His duty is to maintain that color, keep it, move with it and plant it if the objective is reached. His job is to not let that flag hit the ground. Can you imagine it? If you made an assault, what’s up front? It’s the commanding officer and color bearer, and you can guess who is going to get shot first.

“Being here on Morris Island, my mind is constantly racing, trying to relive the whole event.”

And that’s what happened with the 54th. But Carney picked up the color and kept it moving. He was shot three times and yet, the way I understand it, it was said that flag never hit the ground. And that’s pure dedication. Can you imagine how Carney was crawling on one knee with that flag? Because he was shot in the leg, but he wouldn’t let it go.

In Vietnam, it was very different. Even in World War I, they still had linear assaults; now you don’t see that anymore. But in Vietnam, we still wanted to get the communist flag. When the North Vietnamese took an area, the first thing they planted was their flag. And that’s an insult to America. So, when you saw that flag, that just made your blood boil. It was the same thing with us, we wanted to take our flag and plant it, to show that “We beat you.”

Being here on Morris Island, my mind is constantly racing, trying to relive the whole event. Relive the charge, relive what it was like. I’m trying to imagine in my head the screams, the crying, the hollering, the barrage of bullets, the artillery. You gotta put all of that into perspective. The men who charged down that beach, knowing what’s in front of them — they weren’t going to be taken prisoner, they were going to be killed — they’re heroes. And being who I am, that makes me feel very proud.

Carney didn’t get his Medal of Honor until 1900 for an action that was in 1863. I didn’t receive a Medal of Honor until 44 years later. The government said it was because of racial discrimination that I didn’t receive the Medal of Honor earlier. But I didn’t ever question it; I was just satisfied with what I had. In fact, I went back into combat for another year, having the Distinguished Service Cross, the nation’s second highest decoration.

On March 18, 2014, I went to the White House and received the Medal of Honor from President Obama. And it was an exhilarating feeling, I just can’t describe. But I told myself that now, I’ve got a lot of work ahead of me because I have a message to share. Young children need to know that people are out there putting their lives on the line for them every day.

That’s what I do today; I go out and I give living history. I talk to students and the people about our heritage, about our military, and about why they should learn about history. We have to honor our heroes, regardless of their race, color, creed, ethnicity. I have made educating the people my life’s task.

Related Battles

1,515

174