In the spring of 1864 Major General William Tecumseh Sherman prepared for a campaign to capture Atlanta. Sherman’s success depended largely on his ability to supply his armies. The Union commander relied on the railroads that ran across Tennessee and into Georgia. One, the Nashville and Decatur, stretched south from Nashville to Decatur, Alabama. There it joined the Memphis and Charleston Railroad and ran east to Stevenson, Alabama. From there the line traveled to Chattanooga and points south.

Responsibility for protecting the Nashville and Decatur line fell to the head of the District of Tennessee, Major General Lovell Rousseau. Rousseau directed the construction of fortifications along the railroad. These defensive features dotted the landscape of Limestone County in north Alabama. A fort stood on the outskirts of Athens, Alabama, along with a fort and blockhouses six miles north of the town where the railroad spanned Sulphur Creek.

The Athens fort “was an earth-work, 180 by 450 feet, surrounded by an abatis of brush and a palisade 4 feet high and a ditch 12 feet wide, was 18 feet from the bottom of the ditch to the top of the parapets”, wrote Lieutenant Henry March, Assistant Inspector of Railroad Defenses. “The embankment was strong enough to resist any field artillery; in fact, it was one of the best works of the kind I ever saw”, he remembered.

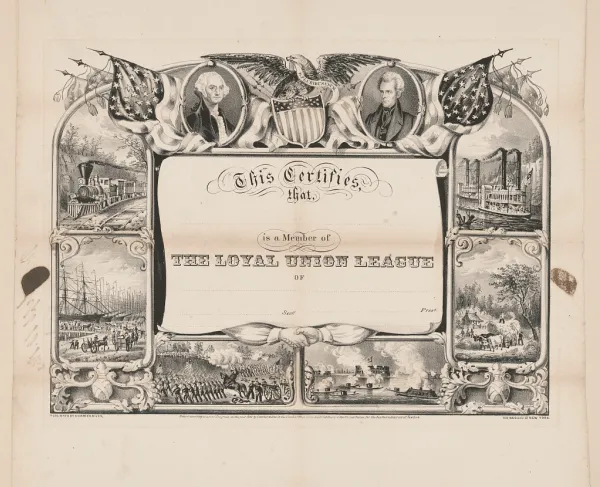

Former slaves likely constructed the Athens fort. Many may have enlisted in the 2nd Alabama Regiment of African Descent, eventually reconstituted as the 110th United States Colored Troops (USCTs). Along with the 106th and 111th USCT the 110th occupied the Athens fort that summer. The 110th’s colonel, Wallace Campbell, commanded the garrison.

Sherman accomplished his objective and captured Atlanta on September 2, 1864. Still, Confederate raids against his supply lines continued. Two weeks after the city’s fall, acting under orders from Lieutenant General Richard Taylor, Major General Nathan Bedford Forrest left Verona, Mississippi with his cavalry command, bent on wreaking havoc along the Nashville and Decatur.

Forrest drew rations at Cherokee, Mississippi and then set his sights on Athens. He dispatched his brother, Lieutenant Colonel Jesse Forrest with his own 20th Tennessee Cavalry and Lieutenant Colonel Raleigh White's 14th Tennessee Cavalry to a point between Decatur and Athens on the night of September 22. These regiments served as Forrest’s vanguard for the advance on the town.

Campbell received word of the Confederate presence around 3 p.m. the next day when a railroad worker reported Forrest’s troopers south of town. The Union commander put a small force aboard a train to investigate and quickly ran into Forrest and White. After a brief engagement, Campbell pulled back toward the town to protect his stores and the fort. The Federals arrived in Athens to find the remainder of Forrest’s cavalry arriving on the field to engage the garrison.

Upon reaching the outskirts of Athens, Forrest sent the 2nd Tennessee Cavalry to cut the railroad and telegraph lines north of town. He deployed Col. Tyree Bell’s brigade to the east with Col. David Kelley’s brigade on Bell’s left. Brigadier General Abraham Buford’s division assumed a position to the west.

Campbell dispatched a contingent of USCTs along with dismounted troopers from the 2nd Tennessee Cavalry (Union) into Athens that night. The sortie temporarily drove some Confederates from the depot and the Union soldiers extinguished some of the fires set earlier before they withdrew. This action ended the fighting for the day.

“Just after daylight on the morning of September 24, they opened on the fort with artillery from three different sides, casting almost every shell inside the works”, Campbell wrote. Forrest’s barrage did little to soften the Union defenses and he was not willing to risk his men in a headlong assault. Additionally, Forrest could not afford to dither long in Athens as Union troops could be expected to reinforce Campbell.

The Confederate commander decided to hedge his bets and send in a flag of truce accompanied with a call for surrender. “I have a sufficient force to storm and take your works, and if I am forced to do so the responsibility of the consequences must rest with you”, Forrest wrote to Campbell. “Should you, however, accept the terms, all white soldiers shall be treated as prisoners of war and the negroes returned to their masters.”

Campbell refused the demand and sent back his own communication. Forrest responded by requesting a personal conference with Campbell to which he acquiesced. The two met between the lines. Forrest then engaged in a ploy of deception as the two toured the Confederate force. He managed to convince Campbell he was heavily outnumbered, and any further resistance was futile.

Campbell’s thoughts undoubtedly turned to the Battle of Fort Pillow earlier in the year. The garrison, made up predominantly of USCTs, refused Forrest’s request to surrender. Following a successful assault that captured the fort, the Confederate general lost control of his men. A period of brutality ensued and the USCT units suffered more than 30% higher casualties than the white regiment in the garrison.

Unwilling to needlessly risk the lives of his men following the inspection of Forrest’s line, Campbell decided to capitulate. “The soldiers were anxious to try conclusions with General Forrest, believing that in such a work they could not be taken by ten times their number” remembered 1st Lt. Robert McMillan of the 110th USCT. “When told that the fort had been surrendered, and that they were prisoners, they could scarcely believe themselves, but with tears demanded that the fight should go on, preferring to die in the fort.”

Just as Campbell laid down his arms, elements from the 18th Michigan and 102nd Ohio arrived on the field to the south. Forrest quickly shifted Kelley to meet the threat. Colonel Thomas Logwood’s 15th Tennessee Cavalry managed to dislodge the Union infantry from a position along the railroad. A counterattack drove Logwood toward the fort, prompting Forrest to commit the 21st Tennessee Cavalry to the fight. The added weight pushed back the Federals and dashed any hope for Campbell’s rescue.

Forrest pulled out of Athens that afternoon and headed to Sulphur Creek Trestle. The Confederates surrounded the garrison on September 25. Forrest deployed his artillery on high ground overlooking the fort and adjacent blockhouses. He then sent Kelley’s brigade in a dash toward the defenses. Kelly’s troopers assumed a position close to the Union works and the Confederate artillery opened fire. The bombardment went on for about two hours and silenced the Union guns. Forrest then demanded the commander, Lieutenant Colonel John Minnis, capitulate. Minnis met briefly with Forrest and agreed to surrender. Forrest moved on toward Pulaski, Tennessee. He fought a brief engagement outside the town and then rode on to Fayetteville and Tullahoma.

Union Lieutenant Colonel Alfred Wade reoccupied the Athens fort on September 28. Wade’s command consisted of elements from the 73rd Indiana, 10th Indiana Cavalry (Dismounted) and a section from Battery A, 1st Tennessee Artillery (Union). Shortly before 3 p.m. on October 1, Buford’s troopers appeared outside Athens. Forrest dispatched his subordinate a few days earlier to burn a bridge over the Flint River and “destroy the Memphis and Charleston Railroad from Huntsville to Decatur.” The Confederates drove in Wade’s pickets before a heavy thunderstorm developed. Both sides continued to exchange fire throughout the night.

Wade, however, was determined not to share the fate of Campbell. The Union colonel decided to innovate. “For two days…I had labored…constructing a temporary bomb-proof of rather a novel character, it being entirely outside of the fort”, he wrote. “This work consisted simply in covering the ditch, which was fifteen feet wide and six feet deep with logs, which with a slight covering of earth would undoubtedly throw off any shot that might strike. The entrance to this underground apartment which would be by a covered passageway under the gate of the fort.”

Buford’s artillery opened around 6 a.m. on October 2. When the barrage intensified, Wade moved his command to the bombproof but left his artillerists and a few soldiers to man the fort. Wade’s guns responded and the duel continued for two hours. The cannons fell silent at 8 a.m. and Buford decided to send in a demand for surrender. Wade summarily refused. Unable to capture the fort for a second time, Buford disengaged and withdrew.

While Wade’s men managed to hold on to the Athens fort, their predecessors faced a grim future, especially the men of the 110th USCT. Rather than treat them as prisoners of war, Forrest sent them to Mobile, Alabama where Lieutenant General Taylor put them to work on the city’s fortifications. The USCTs were repatriated when Taylor surrendered to Major General Edward Canby in May 1865. They returned to their regiment and served until February 1866. Upon their discharge, many returned to Limestone County and Athens.

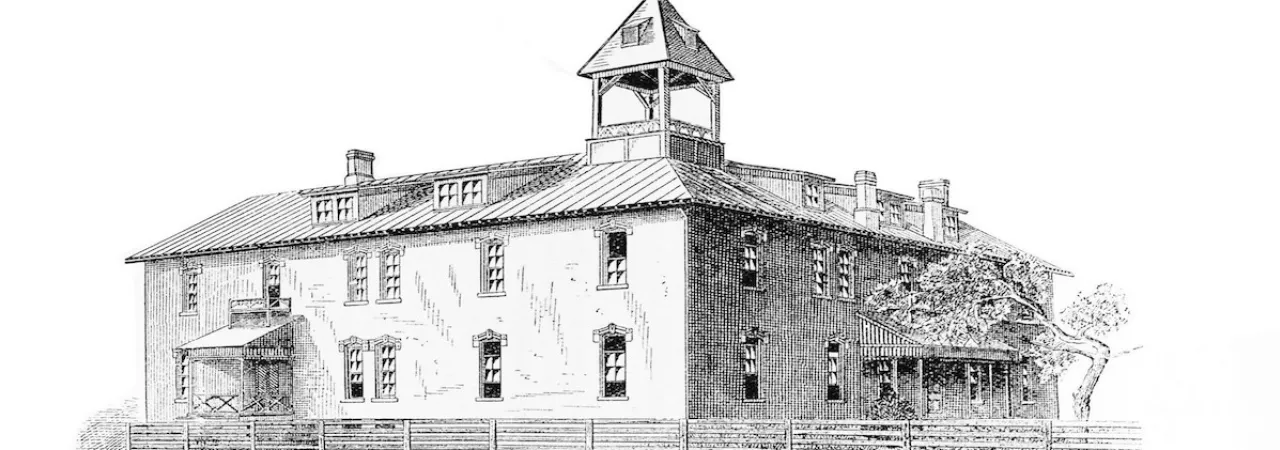

They found a home forever altered by war. One of the many changes to Athens impacted the former USCTs and their descendants for generations to come. Mary Fletcher Wells, a native of Michigan, arrived in Athens in the spring of 1865. A member of the American Missionary Association, Wells established Trinity School in the war damaged white Baptist church near the railroad depot to educate former slaves and African Americans. Wells continued her work in the community when she founded Trinity Congregational Church in 1872. With a strong emphasis on education and religion, Trinity alumni went on to teach and pastor churches across the United States. Throughout the Jim Crow era and Segregation, Trinity was the only institution in Limestone County that offered an education to African Americans.

Trinity burned in 1907. The following year, the school relocated to “fort field”. Now named Fort Henderson after Perry Henderson who surveyed the area in the early 1890s, it became Trinity’s home for the next sixty three years. Trinity closed in 1970 after the passage of Freedom of Choice. Still, its influence echoes through the generations. Today, alumni and their families gather annually for reunions at Fort Henderson and Trinity School.

In the spring of 2019, the American Battlefield Trust, in partnership with the Limestone County Archives and local historians, undertook an effort to interpret the Fort Henderson site. Spearheaded by the funding of Alabama native and Alumni Board member Paul Bryant, Jr. six new interpretive signs were installed at the site in August 2020.