“The Most Terrible Ordeal of My Life”: The Battle of Fort Pillow

With momentum created by his victory at Okolona firmly in hand Confederate Maj. Gen. Nathan Bedford Forrest prepared to launch an expedition from northern Mississippi in early March 1864. The Confederate cavalryman had two divisions under his command led by Brig. Gens. James Chalmers and Abraham Buford. Forrest hoped to upset enemy activity, recruit soldiers and gather supplies.

Although repulsed in their efforts outside Paducah, Kentucky, the Confederates enjoyed success at Union City and Bolivar, Tennessee. By the first days of April, Forrest decided to turn his sights on an enemy fortification on the banks of the Mississippi River, Fort Pillow.

Named for Confederate General Gideon Pillow, the work had been constructed to protect Memphis. When the city fell to Union forces in June 1862 it was abandoned and occupied by the Federals, who improved upon the defenses. Built in the shape of a half-moon and facing east, the fort consisted of three separate lines. Major Lionel Booth commanded the garrison which consisted of a section from the 2nd U.S. Colored Light Artillery, one battalion from the 6th U.S. Colored Heavy Artillery and the Unionist 13th West Tennessee Cavalry. The three units combined numbered almost 600 men.

Forrest planned to use Buford’s troopers as a diversion while Chalmers assailed the fortification. Around sunrise on April 12, three years to the day of the opening of hostilities at Fort Sumter in Charleston Harbor, the lead elements of Chalmers’ division approached Fort Pillow. Chalmers quickly drove in Booth’s pickets and deployed for battle. “Our garrison immediately opened fire”, remembered Lt. Mack Leaming, the adjutant of the 13th West Tennessee Cavalry. “The firing continued without cessation, principally from behind logs, stumps and under cover of thick underbrush and from high knolls, until…the rebels made a general assault on our works, which was successfully repulsed with severe loss to them.” During the assault, Maj. Booth, “passing among his men and cheering them the same…was struck in the head by a bullet killed.” Command devolved upon the 13th West Tennessee Cavalry’s Maj. William Bradford.

Forrest himself arrived on the field about 10 a.m. in time to see a second attack repulsed. Unable to make any headway, around mid-afternoon, he decided to send over a message under a flag of truce. “Your gallant defense of Fort Pillow has entitled you to the treatment of brave men”, the note read. Forrest demanded unconditional surrender with assurances that the garrison would be treated as prisoners of war. Otherwise, if Forrest was forced to take the position by storm, the battle’s consequences would fall on the shoulders of the Federal commander.

Lt. Leaming was designated to meet the Confederates. He rendezvoused with the flag party 150 yards from the earthworks and requested one hour to consult with the other officers. Leaming had barely reached the fort when a second message was communicated and he went out to receive it. Impatient, Forrest himself had ridden forward. Confronting Leaming, Forrest demanded the garrison’s surrender in the next twenty minutes. Leaming carried this new ultimatum to other officers who voted unanimously not to capitulate. When Leaming delivered this decision in writing, Forrest read the dispatch, quietly saluted and walked away.

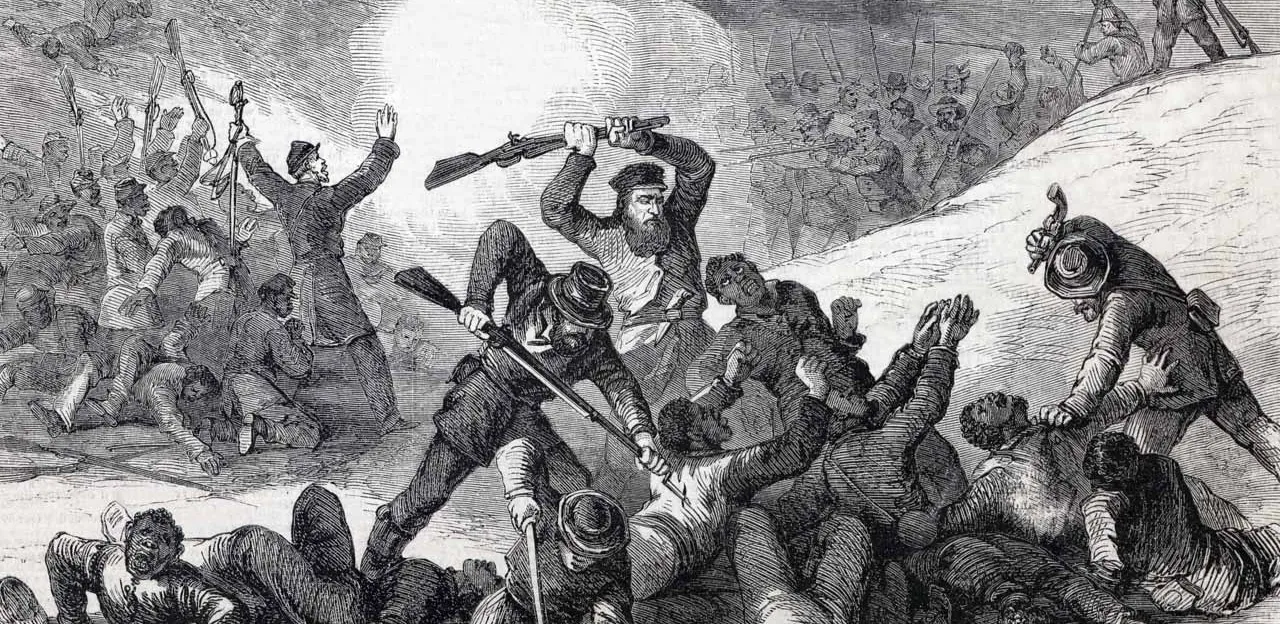

Forrest returned to his lines and promptly gave the order to advance. “The bugle then sounded the charge”, Chalmers recalled and “a general rush was made along the whole line, and in five minutes the ditch was crossed, the parapet scaled, and our troops were in possession of the fort.” “As our troops mounted and poured into the fortification the enemy retreated toward the river arms in hand and firing back”, Forrest wrote.

Organized Union resistance soon collapsed, however the Confederates were enraged to find they were opposed by black troops. Although the major combat had ceased, the killing continued. Many of the Confederate troopers clubbed or gunned down the African Americans, despite their pleas of surrender. This brutality was not just confined to the artillery units. The Confederates turned on the Tennessee troops who they considered to be turncoats. It was some time before the officers could restore some semblance of control. Among the dead was the fort’s temporary commander, Major Bradford.

When the firing finally came to an end, Forrest sustained casualties of 14 killed and 86 wounded. The Federals lost about half of their total strength with the black units losing 64% killed outright, more than 30% more than the white units. Today, 155 years later, historians still debate the details of Fort Pillow. It is clear there was a stage of orthodox fighting by both sides followed by a second phase of brutality. While Forrest did not give an order to wipe out the entire garrison, he lost control of his men and certainly could have done more to save the lives of the Union soldiers. At the same time, the garrison had outrightly refused an appeal to surrender. Still, had the black troops formally laid down their arms, there could not have been an expectation that they would all have been treated as prisoners of war.

Remembered as a “massacre”, Fort Pillow became a rallying cry in the North and a dark chapter of the American Civil War.