In November, 1861, Union ships sailed toward Port Royal Sound in South Carolina. Flag Officer Samuel F. Du Pont, eventually promoted to Rear Admiral, and Brigadier General Thomas W. Sherman planned an amphibious attack against Fort Walker, on Hilton Head Island, and Fort Beauregard, on Phillip’s Island. Both forts protected Port Royal Sound near Charleston, South Carolina. The people in the North wanted a short war. They hoped that a Union blockade along the Southern shoreline could eliminate, or limit, the movement of supplies moving in or out of the Confederacy. As part of this “Anaconda Plan,” a blockade could only be sustained if Union boats had a safe place to refuel, restock, and repair their ships along the Southern coastline. Port Royal Sound would be an excellent safe harbor.

Fort Walker and Fort Beauregard were not the only structures on the island, however, nor were the Confederate soldiers who manned them the only inhabitants. Hilton Head and Phillip’s Island were part of a chain of islands off South Carolina’s coast called the Sea Islands. With rich soil, easy access to fresh water, and plenty of sunlight, these islands were well suited for agriculture. Southern planters bought large swaths of this land and established plantations that grew cash crops such as rice, indigo, and cotton. Because of the remoteness and the humid, hot summers, most planters spent little time on the islands. They lived in the nearby capital at Charleston and left their plantation in the hands of white overseers. Some 10,000 African American slaves lived and worked on the Sea Islands. Few slaves were transported off the islands as the Civil War began.

On November 1, 1861, a fleet of 77 vessels, including 17 warships, set sail toward South Carolina from Hampton Roads, a body of water near Norfolk, Virginia. Two days later, after a gale damaged several vessels, a 60-vessel fleet emerged on Port Royal Sound. After several days of reconnaissance, DuPont and Sherman agreed that it was time to attack. On November 7, Union ships began to approach the two forts. Confederate soldiers at Fort Walker fired on the ships. With little help from Confederate gunboats and lacking enough guns for defense, Confederate soldiers abandoned Forts Walker and Beauregard. With fewer than 100 casualties, the Forts were under Union control.

With control of the Forts, the Union army began to set up a military base on the two islands. Unexpectedly, 150 African American slaves left there, now unsupervised, asked for aid from the occupying Union soldiers. By the end of November, those 150 African Americans had become “contraband” of the Union Army. By February 1862, the number had risen to 600 as more flocked to the protection of Union forces.

In August 1861, Congress passed the Confiscation Act of 1861 that stated that any property used by the Confederate militia, including slaves, could be confiscated by Union forces. These “confiscated” slaves, who usually self-surrendered to Union forces, were classified as “contraband” in Union correspondences and paid for work in the Union army.

Unfortunately, Union military bases encountered difficulties regarding how to house and employ these large influxes of contrabands. From February to October, 1862, more than 600 former-slaves lived in sub-standard housing near Forts Walker and Beauregard. Sanitation issues proliferated and tensions rose between Union soldiers and the contraband to a degree that Union leaders began discussing the creation of a separate “Freedman Village” outside of the Union base. Major General Ormsby M. Mitchel, Commander of the Department of the South, was tasked with the creation, layout, and organization of this new town. Because of his work, and his premature death on October 31, 1862, from yellow fever, the Freedman Village was named Mitchelville in his honor.

The government provided each family unit with one-quarter acre of land and the materials to build a house. Roads connected the parcels of land with dedicated public spaces that included churches, schools, and businesses. While the U.S. government provided the land, resources, and some direction, Mitchelville was predominately constructed and managed by Freedman, who held elections, enacted laws and maintained order. In addition, three churches, four stores, and a school were built for the community. The school was the first compulsory school system in the state of South Carolina for children age 6 to 15. Residents of Mitchelville worked as day laborers for the Union Army and could earn between four and twelve dollars per month from their labor. Family gardens fed the village and neighbors sold and trades goods with each other. After the creation of the United States Colored Troops (USCT) in 1863, USCT soldiers established Fort Howell to help protect Mitchelville from Confederate attack and fortify the town.

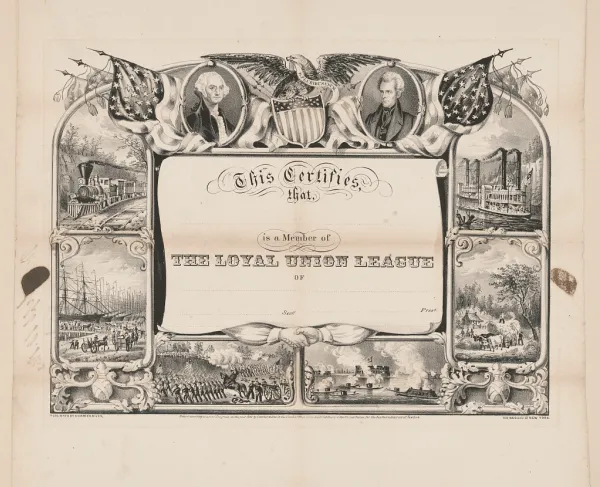

Mitchellville became a prototype for the Reconstruction-era. It was the first of several towns established under the Port Royal Experiment, one that aimed to determine whether former slaves could become average American citizens if given materials to build homes and an area to settle. These villages aimed to debunk Southern-propagated myths that African Americans were inherently inferior, unintelligent, and unable to be anything but slaves. While the Port Royal Experiment was a success, it was short-lived. The United States government did not institute these reforms on a national scale.

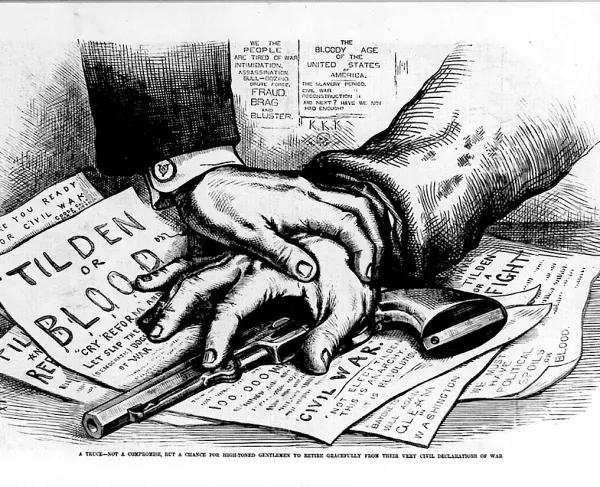

By 1865, Mitchelville had a population of 1,500 freedmen. On December 6 of that year, the Thirteenth Amendment was officially ratified and slavery was officially abolished in the entirety of the United States. For three more years, Mitchelville residents acted as day laborers for the military that still occupied Hilton Head and Phillip’s Island. By 1868, all military personnel had left and the land on which Mitchelville was situated wasn’t deeded to the residents by the United States government or the Union Army. Rather, as an act of goodwill by the government toward the South, land previously confiscated by the North was returned to its pre-Civil War owner. In 1875, Mitchelville was returned to the Drayton family that had previously used the land as a plantation. Fortunately, the Drayton family sold the land to Mitchelville residents. Unfortunately, after the expense of purchasing the land and the limited economic opportunities on the island, residents began to leave town and move to mainland South Carolina. This once bustling town shrunk until only one or two extended families remained. By the 1930s, Mitchelville no longer existed.

When the Union Army landed on Hilton Head and Phillip’s Island, they were expecting to gain a military advantage. They did not expect to face questions about the status of slaves and slavery in a war-torn country. Mitchelville’s story highlights the social and political decisions that dictated African American’s lives during and after the Civil War. This town was a testament to what Reconstruction could have looked like when African Americans were given resources to create a thriving community. However, this town also shows the financial difficulties faced by African Americans during the Reconstruction and post-Reconstruction eras. In the 1990s, renewed interest in Mitchelville resulted in the placement of historical markers near the now-disappeared town. In addition, archeological digs uncovered a rich collection of artifacts from the previous residents. Recreations of the town are underway to highlight and discuss African American lives during the Civil War, Reconstruction, and the post-Reconstruction era.

Learn more about Mitchelville here.