Approximately three million... that's how many horses and mules traveled with the Union and Confederate armies during the Civil War, some carrying the most well-known military minds on their backs. During this tumultuous period, horses provided mobility, power and support to soldiers on and off the battlefield. As the primary mode of transportation for cavalry and artillery units, these draft animals were the first on the field from Bull Run to Appomattox Court House, allowing units to be swiftly deployed and positioned strategically. They transported supplies, equipment and wounded soldiers, giving armies the ability to sustain their operations and maintain their fighting strength.

Strong and fast steeds also were a means for relaying make-or-break communication during the war. Dispatch riders galloped across the front lines, delivering crucial messages and orders between commanders and troops. In an era without the convenience of modern communication, their presence enabled timeliness and accuracy on the chaotic battlefield.

During the largest cavalry battle ever fought in North America, the Battle of Brandy Station on June 9, 1863, nearly 20,000 horsemen clashed just northeast of Culpeper, Virginia. For 14 hours, pistols, sabers and war horses decided the fate of Gen. Robert E. Lee’s invasion of Pennsylvania. Considered a Union defeat, the battle still proved to have a positive impact on the morale of the Northern horse soldiers. In the words of Confederate Maj. Gen. J.E.B. Stuart’s chief aide, “Brandy Station made the Federal cavalry.” The story of these war horses and their riders is certainly an element of the upcoming Culpeper Battlefields State Park that future visitors can look forward to in June 2024.

But, in considering the great impact that horses had during the Civil War, it begs the question: Who were the steeds carrying those larger-than-life figures that history books will never forget, from Ulysses S. Grant to Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson?

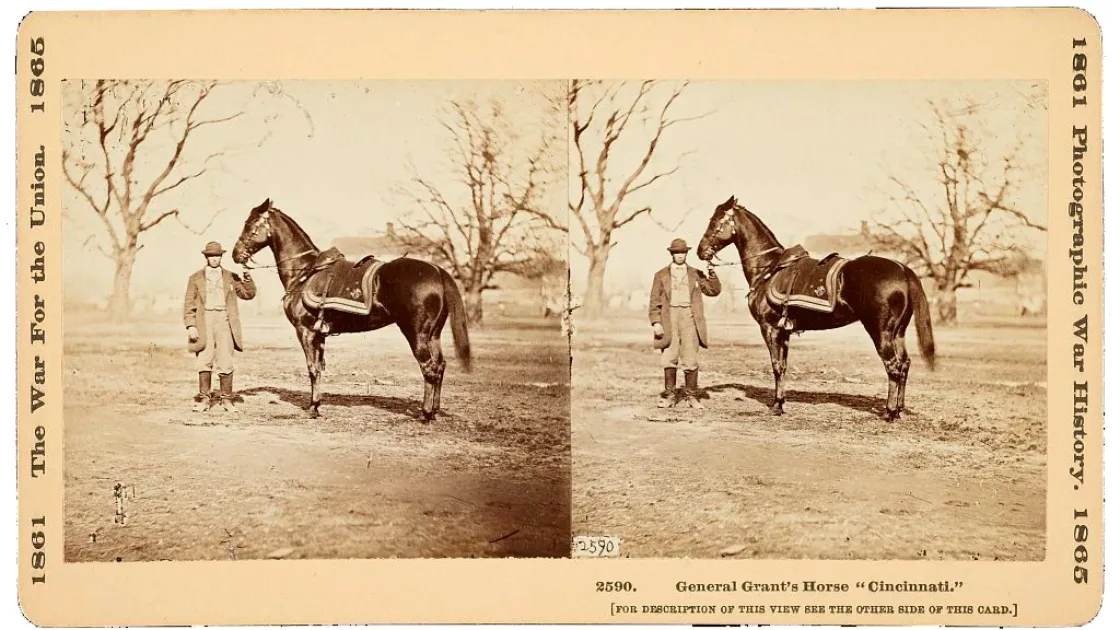

Cincinnati

Shortly after the Battle of Chattanooga, Ulysses S. Grant was gifted a chestnut-colored horse to whom he took an immediate liking. Named Cincinnati, he deemed the horse his favorite by the time of the 1864 Overland Campaign.

Cincinnati hailed from a distinguished family. His father, Lexington, was recorded as the country’s fastest four-mile Thoroughbred. Cincinnati was well suited for combat; many observers remarked on the horse’s love for the sound of battle. During the war, only three men were allowed to ride Cincinnati: 1) Grant himself, 2) Grant’s childhood friend, and 3) President Abraham Lincoln. When Lincoln visited Grant’s headquarters at City Point, Virginia, the president rode Cincinnati to and from meetings.

Cincinnati was present when Lee surrendered his army at Appomattox AND carried the victorious Grant away to a grateful nation. Grant had to turn down several offers to buy his beloved horse; one such offer totaled $10,000 (which is the approximate equivalent of $188,000 today). When Grant was elected President of the United States, Cincinnati came to the White House with his owner. The pair remained inseparable until old age dictated that Grant send Cincinnati to the farm of his old friend Admiral David Ammen. Cincinnati lived out the rest of his days in Maryland until he passed away in 1878.

Lee’s Traveller

Perhaps one of the most famous horses of the American Civil War, Traveller was born in Greenbrier County, West Virginia. At birth in 1857, Traveller did not yet have his famous name; instead, he went by “Jeff Davis,” an homage to, at the time, the United States’ Secretary of War, Jefferson Davis.

As a colt, Traveller took first place at fairs in Lewisburg, Virginia, in both 1859 and 1860. This was unsurprising, given that Traveller’s father, Grey Eagle, had won some $20,000 at the Kentucky State Fair in previous years. When the American Civil War broke out the following year, Traveller was purchased from his original owners by Capt. Joseph M. Broun of Governor Henry Wise’s 3rd Infantry in Western Virginia. Broun renamed the horse “Greenbriar.” Soon, Robert E. Lee arrived to inspect the soldiers in the mountains; he was commander of all Virginia forces and a full Confederate general.

General Lee took a liking to the horse, and he soon purchased Greenbriar from Broun in the spring of 1862. For the entire war, Lee rode Traveller into battle until he rode away from the McLean house after surrendering his army at Appomattox. After the war, Traveller followed Lee into retirement at Washington College, later Washington and Lee University. Traveler died a year after his longtime rider and is buried just yards away from him in Lee Chapel.

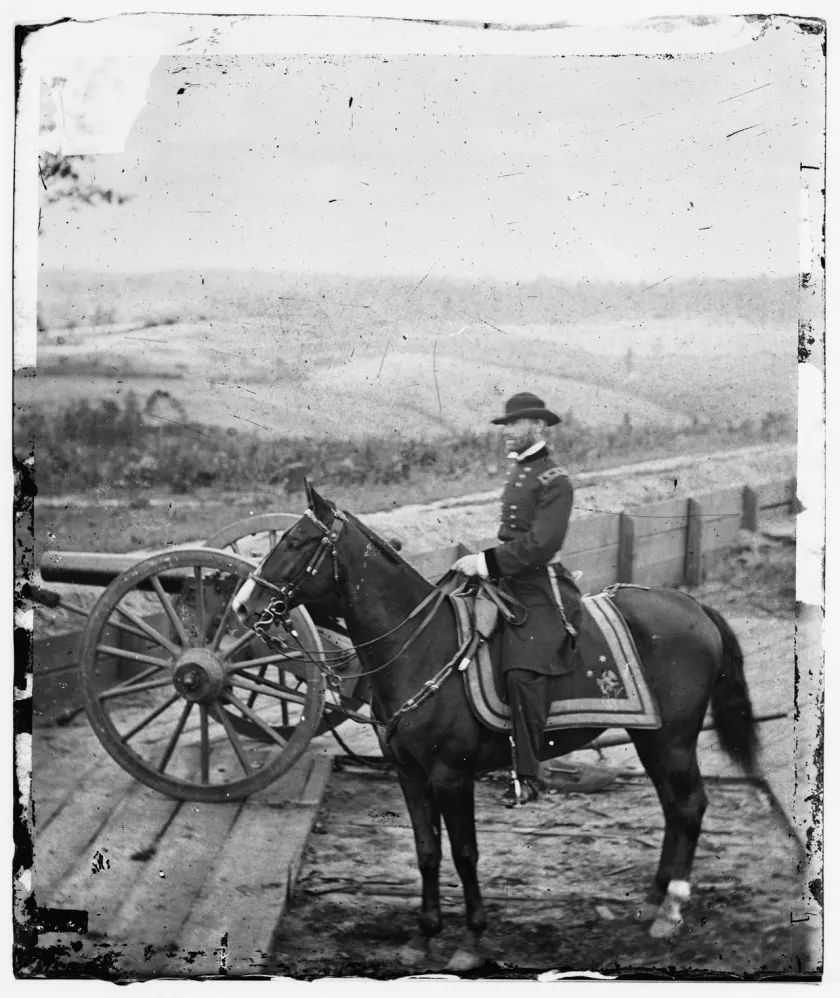

The Mystery of Duke

When an article published after the war took account of Gen. William T. Sherman’s horsemanship, they recorded that, “General Sherman was a nervous and somewhat careless rider. He wore his stirrup-leathers very long, seeming to be almost all the time standing in the irons. This appearance was intensified by his habit of rising in the stirrups on reaching a turn in the road or some advantageous point of observation. While always careful of his animals, Sherman did not appear to have that fondness for them that is so common among good horsemen.”

So who was the horse that carried the famous firebrand of the American Civil War? Thankfully, Sherman told everyone in a letter. In 1888, famous portrait artist E.F. Andrews wrote to Sherman to inquire who his favorite wartime horse was. Sherman replied that “...my favorite horse during the war was the one I rode at Atlanta, and whose name was ‘Duke.’ He was a bright bay, had a white star on his forehead, and one white foot (left hind foot). I have a good portrait of him by Trotter of Philadelphia now hanging in my office.”

Newbold Trotter’s portrait of Sherman riding Duke still survives, but not much is known about Duke’s life after, or even during, the Civil War. Duke was the horse that carried Sherman on his famous March to the Sea. A photo even survives depicting the two outside of Atlanta. After the war, Sherman was in command for a time in Mississippi and eventually rose to commanding general of the United States Army. While history doesn’t note the fate of Duke, it can be speculated that Sherman thought of his mount and the wartime experiences they faced together when he glanced to Trotter’s painting in his office.

Little Sorrel

When Confederate forces captured the Union garrison at Harper’s Ferry, West Virginia, in 1861, several horses were among the many supplies gained. After, the Confederate commander Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson came and purchased two horses: a larger horse called Big Sorrel and a smaller horse he dubbed “Fancy,” whom he planned to give to his wife, Mary Anna Jackson. However, Jackson took a liking to the small horse. He renamed him Little Sorrel — a name that would gain fame in the years to come.

Little Sorrel was born on the farm of Noah C. Collins near the small town of Sommers, Connecticut. He was a descendant of the original Justin Morgan horse born in Springfield, Massachusetts, in 1789. Morgans were prized horses — said to be calm under fire and built perfectly for army life. Little Sorrel was no exception. Several of Jackson’s staff observed the steed’s disregard for danger and apparent love of combat, much like his owner. Little Sorrel served Jackson for nearly his entire time as a Confederate officer; the mount saw battle at such places as the Virginia Peninsula, Antietam and Fredericksburg. It was Little Sorrel that Jackson rode between the lines at Chancellorsville when he was shot and mortally wounded by friendly fire.

After the Civil War, Little Sorrel moved to Mary Anna Jackson’s family farm in North Carolina. In 1883, she donated Little Sorrel to the Virginia Military Institute (VMI). For the next couple of years, the horse wandered the grounds of VMI, a living reminder of the school’s most famous instructor and one of the last equine links to the Civil War. Little Sorrell died in 1886 at an astounding 36 years of age, exceeding the average horse’s lifespan by six years.

Recognizing the Sacrifice

Of the roughly three million horses and mules that took part in the conflict, it’s estimated that half perished in the process. But their contributions have not gone without recognition. In places like Middleburg, Virginia, and Murfreesboro, Tennessee, memorials stand to pay tribute to the horses and mules who were casualties of war. Between battle and the grueling work of hauling heavy supplies and weapons, these creatures were pushed to their limits.

In Middleburg, the “Bridled Veterans” Horses and Mules Memorial was sculpted by Tessa Pullan in 1997. It acknowledges that of the approximately 1.5 million draft animals lost to the war effort, that “many perished within twenty miles of Middleburg” — during three impactful cavalry-heavy battles in June 1863. It sits outside the National Sporting Library and Museum.

Meanwhile, in Murfreesboro — upon the Stones River National Battlefield — there stands a statue commemorating the 32,000 horses and mules that served in the Battle of Stones River. Of this figure, it is said that roughly 3,000 were either killed, disabled or captured.

These four-legged creatures were a crucial thread in the complex fabric of the Civil War, and their fierce and determined spirits are far from forgotten.