Nathanael Greene Monument, sculpted by Herman Packer, Guilford Courthouse National Military Park, Greensboro, N.C.

When Major General Nathanael Greene arrived in Charlotte, North Carolina, on December 2, 1780, as the new Continental Army Southern Department commander, he was taking over a theater that had seen few Patriot victories over the past year. But a series of swift and masterful maneuvers, augmented by audacity and sheer luck, shifted the balance in just four months.

The situation Greene inherited was dismal. Charlestown, South Carolina, besieged by British forces under Lieutenant General Sir Henry Clinton, had surrendered on May 12, 1780. This catastrophe included the surrender of more than 5,000 Continental soldiers and southern militia troops. The victory also allowed the British to quickly overrun the state’s backcountry and establish several garrisons at Camden, Ninety Six, Cheraw, Georgetown and other posts. And although Clinton returned to New York City in late June, he left behind several thousand men commanded by Lieutenant General Lord Charles Cornwallis, who had seen extensive service in America by that time. His Lordship wasted no time marching his troops into the interior of the state in an attempt to gain British control over the American rebels.

Meanwhile, by the end of July, the Continental Congress and several southern states had cobbled together a new army in North Carolina, supported by militia companies. The new force, however, lacked adequate arms, food, clothing and equipment. Major General Horatio Gates, the “hero of Saratoga,” was given command of the department, against General George Washington’s better judgment, and quickly moved his weary troops toward Camden, South Carolina, where Cornwallis had concentrated a veteran army of about 2,000 soldiers.

Gates’s approximately 5,000 troops arrived tired and famished several miles north of Camden by August 14. It was coincidence that both sides chose to move after dark the next evening. After an engagement that night in the piney woods north of Camden, the British attacked Gates’s lines at dawn, routing the Americans and earning a “compleat victory” in the hour-long struggle.

The Patriot troops fled to North Carolina, and, in early October, Washington, with the authority of Congress, chose Greene as a successor to Gates. Leaving West Point, New York, almost immediately, he and his staff rode south toward the Carolinas, meeting with state governors and legislatures along the way to implore them to send more troops and supplies to the army at Charlotte. Greene arrived at the outset of December and assumed command the next day, as Gates departed the army’s encampment.

Cornwallis, meanwhile, was not idle, advancing into North Carolina and occupying Charlotte after a brief skirmish on September 26. But in the second week of October, disaster struck the British when a mounted force of American frontiersmen surrounded and annihilated Major Patrick Ferguson at Kings Mountain. The stunning victory for the American cause forced Cornwallis to withdraw to Winnsboro, South Carolina, where his worn-down, fever-ridden soldiers recuperated until early January.

Greene took stock of his new army’s deplorable condition: His soldiers were poorly clad and shod and ill-fed, and many were without proper arms and accoutrements. To ease the logistical problems he faced, Greene made a bold choice with his outnumbered force, moving east along the Pee Dee River, where he hoped to find it easier to supply them. A smaller force of dragoons and light troops remained in the area south of Charlotte to threaten British posts west of the Catawba River and gather more militia. This detachment was led by Brigadier General Daniel Morgan, a dynamic leader and experienced officer capable of independent command, who had arrived at Charlotte in October.

Now rested and expecting reinforcements, Lord Cornwallis resumed his campaign to conquer North Carolina in mid-January 1781. To eliminate Morgan’s threat to the South Carolina backcountry, Cornwallis dispatched a fast-moving column of infantry, artillery and dragoons — about 1,000 British Redcoats and Loyalists led by Lieutenant Colonel Banastre Tarleton, a young, hard-hitting cavalryman with a reputation for ruthlessness and impetuosity.

Tarleton pursued Morgan through a cold winter rain, and finally drew close enough to attack the retreating Americans on January 16 at a large open area called the Cowpens. Morgan was ready for the dawn assault, his men arrayed in three lines to accommodate the typical weakness of the militia: a propensity to flee in the face of a bayonet-wielding enemy. Morgan put riflemen first, then the militia — each with orders to fire a few volleys, then retire to the rear. His most trusted units, Maryland, Virginia and Delaware Continentals, made a third line on a low hill, with mounted troops to the rear hidden by the ridge.

True to form, Tarleton charged ahead with only part of his detachment on the field. Morgan’s deployment worked to perfection, and almost all of Tarleton’s force was captured along with their artillery, although the brash commander escaped east with a few dozen troops back to Cornwallis’s camp.

Morgan could not rest on his laurels. With hundreds of prisoners in tow, he sped north, hoping to cross the Catawba River near Charlotte and avoid Cornwallis’s army. By the end of the month, with his troops across the river and the Cowpens captives moved into North Carolina, Morgan deployed his forces to guard several Catawba fords. Cornwallis, his pursuit inexcusably slow, even allowing for rain-swollen streams, finally reached Ramseur’s Mill on January 25 and ordered the army’s nonessential baggage burned to quicken the pace. With a forced crossing of the Catawba under fire from North Carolina militiamen at Cowan’s Ford on February 1, the 2,800 Redcoats were poised to strike.

General Greene had arrived at the flooded Catawba River on January 30 to join Morgan ahead of the main army under Brigadier General Isaac Huger, now marching west from their Cheraw, South Carolina, camps. Greene prudently ordered Morgan to cross the Yadkin River at Trading Ford near Salisbury, then move to the tiny hamlet of Guilford Courthouse 60 miles to the northeast. They were soon joined by Huger’s troops and the Continental dragoons under Lieutenant Colonel Henry “Light Horse Harry” Lee by February 7.

Cornwallis’s army had pursued Greene but halted at Salisbury on February 4, unable to cross the Yadkin as the Americans had taken all available boats. Rather, the British crossed the river upstream at Shallow Ford, then marched quickly to the Moravian village of Salem, 25 miles from Guilford Courthouse. This movement placed the British on the same side of the Yadkin and dangerously close to the American army of about 2,000 men. Greene had to put another river between his troops and the enemy, so after discussing the situation with his officers — less Morgan, absent with debilitating medical complaints — Greene decided to move northeast toward safety and to resupply across the Dan River.

But where to cross? The closest point was Dix’s Ferry, just inside Virginia, but the British at Salem were equidistant to this point and could threaten the movement. Instead, Greene chose to use two crossings farther downstream, Boyd’s and Irwin’s Ferries, near present-day South Boston, Virginia, on a section of the Dan where the Americans had previously collected boats for transport. He had to be careful, however, because getting to the ferries and crossing before Cornwallis could overtake them was not guaranteed.

To execute the maneuver known to history as the “Race to the Dan,” Greene employed a ruse to help keep the British off his tail, splitting his army again. On February 10, Greene led the main body northeast toward Virginia from Guilford Courthouse, while a smaller rearguard detachment of dragoons and light troops, commanded by Colonel Otho Holland Williams of the Maryland Continentals, fooled Cornwallis into following their march for Dix’s Ferry.

For the next four days, Redcoats chased the rebels across a largely unsettled Piedmont region of sandy roads and tall pines. Often, Tarleton, leading his dragoons in the British pursuit, closed within a hundred yards of the fatigued Americans, who were subsisting on less than three hours sleep and little time to eat their bacon and ground corn. Early on the morning of the 14th, Greene ordered Williams to shift his route to the main body’s path as the army approached the ferry sites. Although Cornwallis doggedly chased his prey, Greene and his troops managed to cross the Dan River on boats collected there weeks before, just hours in advance of the British appearing on the south bank. Williams called the “race” one of Greene’s most “masterly and fortunate maneuvers.”

While the exhausted Americans rested and refitted on the north bank, Cornwallis moved his men south to Hillsborough by February 20. Once Greene pursued the British after recrossing the Dan, the two belligerents engaged in a period of several weeks maneuvering between Hillsborough and the Deep River settlements (near present-day High Point), including a few bloody skirmishes. As Cornwallis marched to the Deep Creek Friends (Quaker) Meeting House on March 13, Greene cautiously pursued him, then brought the army to Guilford Courthouse on the 14th. There, hundreds of militia companies and a contingent of newly raised Continentals from Virginia joined the American army, swelling its ranks to over 4,000 soldiers. That evening, he decided to attack the British at their encampment the next day.

In the pre-dawn darkness of March 15, 1781, Cornwallis roused about 2,000 troops and set them off on the New Garden Road to attack Greene’s army, only a dozen miles away. Once Greene learned from his scouts that the Redcoats were on the move, he took up a defensive position and deployed his troops in three lines, much as Morgan had done at Cowpens two months earlier. In the first line he positioned the North Carolina militia at the edge of an open field along the New Garden Road, situated at the woods’ edge behind a rail fence; they were supported by more reliable troops on each flank — riflemen and Lee’s Legion on the left, and Washington’s cavalry and a company of Delaware Continentals on the right. Two artillery pieces took up a position on the road.

In the second line in wooded terrain, Greene deployed the two brigades of Virginia militia, many of whom had seen prior service in the Continental Army. Behind them, several hundred yards away on a high ridge, Greene placed his Continentals — two regiments from Maryland and two from Virginia, supported by two more artillery pieces — along the Reedy Fork Road north of the small courthouse.

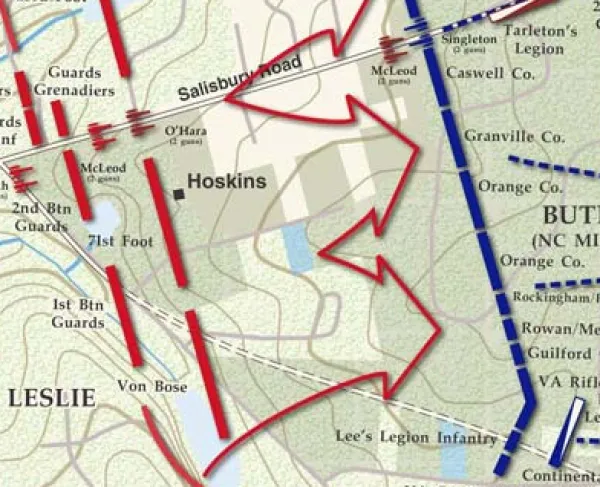

In the morning, a running cavalry fight along New Garden Road developed as the Redcoats advanced. Once near Greene’s lines, Cornwallis deployed his foot regiments on either side of the road, with artillery in the center, and Tarleton’s dragoons held in reserve to exploit any success. The British commander’s plan was simple: strike head on with relentless bayonet assaults.

Upon the initial British assault, the first line of North Carolina militia fled the field, some without firing a shot. The flanks offered some resistance, but soon the British reached the second line. Deadly fire from the Virginians in thick woods and brush caused Cornwallis’s attack to become disjointed, with elements veering off to chase retreating rebel troops. Eventually, the Virginians retreated under British assaults, and several regiments of Redcoats came upon the third American line, where the Continentals initially put up a stout defense. But when the British 2nd Battalion of Guards charged Greene’s left flank, they routed the newly raised 2nd Maryland regiment and threatened Greene’s rear. The fighting turned into a confusing melee and Greene, unwilling to risk a catastrophic defeat, left the field to the enemy. The Americans retreated north in good order as most of the militia dispersed immediately.

Cornwallis had won a Pyrrhic victory, losing about 25 percent of his men. Most of Greene’s troops had fought hard, acquitted themselves well and were fit to fight another day. Low on supplies and greatly reduced by his casualties, Cornwallis retreated to the coast, reaching Wilmington on April 7 after a slow, frustrating march. His invasion of the state had been defeated in a campaign brilliantly executed by General Greene.

Related Battles

1,310

532