The strategy employed by the British government and its military forces during the American Revolution was thoroughly flawed from start to finish. It was difficult to prosecute a war on land and sea in the age of sail when the primary strategists were 3,000 miles removed from the theater of war. King George III, most members of his cabinet, and most members of Parliament were out of touch with their colonists across the Atlantic. And most had never set foot on a continent where they now intended to undertake major military action.

When the war broke out in the spring of 1775, the area surrounding Boston was the epicenter of the rebellion. This was not unknown to the British government, which had closed the port of Boston following several riots, the assault on the schooner Gaspee (moored near inland Rhode Island), and the infamous Boston Tea Party of December 1773. Plans were to isolate the rebellion to the New England colonies, but how to achieve this was met with confusion and incoherence on the part of the King’s ministers. Lord North, the King’s chief minister to Parliament and disciple of British governance, was not a strong wartime leader and often struggled to provide a clear and concise blueprint for action. On the other side of planning was George Germain, Secretary of State for the American Department. Germain, an overly confident former military officer, was less a military strategist as he was a personality to dislike. Germain did not take criticism lightly and was at odds with other members of Parliament who questioned his planning. Nevertheless, King George III held his confidence in these men.

One of the British government's primary blunders was its inability to create a coherent plan for eliminating the rebellion before its provocations spread throughout the other colonies. In hindsight, this may have been a futile endeavor, for the colonies, though clearly different in many regards, did share similar feelings regarding their status as British subjects. Where they differed was with a desire to be recognized as autonomous participants within the British Empire. This perspective was lost on many of Parliament’s members, and especially on the King. Had a plan been implemented to settle initial hostilities in Massachusetts before April 1775, perhaps the colonies would have remained committed British subjects. But it seems both an indifferent – and at times snobbish view – of Americans by mainland Britons, and an uncorked sense of continental liberalism by Patriots were increasingly at odds with how British North America had been managed and allowed to exist in the prior decades. The seemingly passive nature of Parliament’s interest in governing its North American colonies prior to 1763 created that autonomous spirit within the colonists. Only after the King came to power in 1760, and the immense debt accumulated from the Seven Years War with France, did foreign policy prioritize how to manage and ultimately tax North American interests.

What complicated matters further played out in real-time once the British army was in North America. Command of the army was complex and divided in a way that made communicating orders difficult to the point of being detrimental to achieving set-forth objectives. Sir William Howe took command of British forces in North America in the fall of 1775. Howe, like most military officers of the time, exhibited a sense of leeway when making decisions in the field that were often counterproductive to the overall objectives of the British war machine. Howe did not always vigorously pursue the enemy, sometimes allowing parties or creature comforts to get in the way of the war. Howe, too, did not always agree with the strategy the King's cabinet laid out. Nor could he decide on his own strategy as evidenced by the three different plans he presented for the 1777 campaign season.

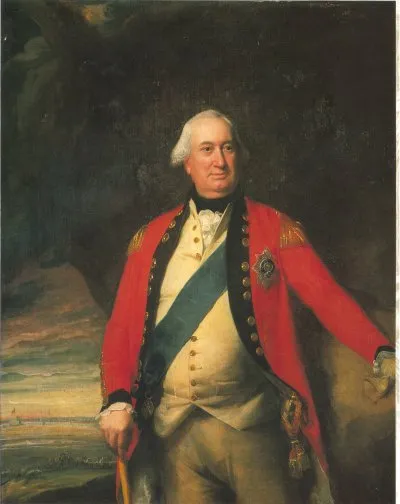

Howe was not alone. His successor, Sir Henry Clinton, also balked at the British strategy. He, too, recoiled at even commanding the British forces in North America after Howe resigned from the position. The same disagreements trickled down to subordinates such as Gen. Charles Cornwallis as well as Gen. John Burgoyne. To make matters worse, these commanders did not always get along with one another. While they may have tolerated each other because of their duty, it’s evident that many of the leading commanders did not hold a very high opinion of their fellow generals, which inhibited British success in some campaigns.

Appointments and elevated egos that challenged rivals within the army led to instances where orders were either changed, disobeyed, or flatly ignored. To complicate matters further, the British navy, perhaps more important to the war’s outcome than the army, reported and received orders from the Board of Trade, not Germain. The army and navy might have received initial orders that paralleled each other, but if a commanding officer or admiral abruptly changed course, the other would often find himself waiting to receive orders from London to verify this change. And London had not made this decision; it was done by the commander in North America on his own. At a time when trans-Atlantic communication was only as fast as the wind could carry a ship, we can see how maddening this could be for trying to achieve a military objective.

We must also recall how, at the outset of the war, British officers in North America were tasked with issuing pardons to colonists who swore allegiance to the King. Some, like Sir William Howe, even initiated diplomatic talks with American representatives. But these were one-sided; Howe had no real authority in brokering a peace treaty and was mainly there to show the American emissaries that London would not stand down. Short of them renouncing the rebellion and the Declaration of Independence, the Americans were not afforded a meeting to negotiate terms for separation. However, the threat of branding colonists as traitors did have the desired effect of seeing thousands of colonists declare their loyalties to the King. In other instances, colonists swore allegiance to whoever’s army was present at the time.

Another tactic used by British officials was to stoke the fears of slave insurrections throughout the colonies purposely. The best example of this was Lord Dunmore’s 1775 proclamation declaring that any enslaved person who escaped and joined the British army would earn their freedom. It is not known how many former slaves left their plantations and entered British lines, but we do know that many were not allowed to fight (and were given manual labor jobs instead), and several thousand settled in Nova Scotia and in western Africa following the end of the war. On the western outskirts of the colonies, British detachments were put there to gain the trust of Native American groups – many of whom looked upon the English favorably and viewed the Americans as hostile invaders.

British advantages in having the best trained and equipped military in the world were no match for realities on the ground. Weather and logistics played a huge factor in eighteenth-century military operations. It was unduly to expect a major engagement in the winter months because of the risk of exposure and the conditions of roads, which often were impassable with snow. Torrential thunderstorms and downpours could wreak havoc on flintlock muskets and powder stores. And the humid, intense summer heat could be more devastating to an army than a bayonet charge. The wool-coated soldier, who carried 70 pounds of equipment, on the march for miles before an engagement, was often the victim of the elements rather than enemy fire.

Other conditions required immediate attention. Firewood was often needed to keep soldiers warm in the winter months and to cook food daily. Both armies were guilty of clearing out thousands of trees over the duration of the war. In more desperate instances soldiers tore down fences, barns, and houses to retrieve whatever wood they could get. Disease, particularly smallpox, was rampant in both army camps. Inoculation provided some protection, but poor health and sanitation conditions were common in encampments, and killed more soldiers than battles. Supply routes were the arterial veins of the army’s sustainability. Both sides tried to disrupt and destroy these precious cargo roads during the war. However, the disruption came at an even greater cost for the British Army, whose supply lines were often longer.

The sheer size of the Atlantic Ocean created a logistical nightmare for resupplying British troops. It could take months for a fully-loaded ship to arrive off the American coast and several more for its contents to reach a British encampment embedded in the hostile countryside. The amount of food required to feed an army is staggering. Armies had several hundred, if not thousands, of horses and cattle for personnel and pulling supply wagons at any given time. These animals required hay, oats, water, and feed too. As a result, the British army turned to foraging or seizing livestock and homespun supplies from the local citizenry. In some cases, this proved to be a useful commodity as loyalist Americans were grateful for the King’s army’s presence. But cases of vandalism and rape by British soldiers often undid these moments of charity.

To complicate matters further, the Continental Army foraged, too, often within close proximity to the British as was the case during the winter of 1777-1778 near Philadelphia. Citizens were asked to contribute what they could to whichever occupying force knocked on their door. As the economy worsened in the ensuing years before the war’s end, resentment between citizens and soldiers, no matter their loyalties, made matters worse. Ultimately, the British army had the disadvantage of being a foreign occupier. The loyalism that remained in the American country was too little for British expectations, and foraging only exacerbated their ability to rely on American support.

Strategy is what dictates the tactics used to achieve a combatant's objectives. Though the initial British strategy was to isolate New England from the remainder of the colonies by way of seizing the Hudson River Valley, as the war evolved, it became clear this approach was failing. Thus, the British set their sights on the southern colonies of Virginia, North Carolina, South Carolina, and Georgia. It was hoped that by isolating the rich southern colonies, the British could sue for peace and walk away with at least a portion of their rebelling colonies. Leaders overestimated the resolve of the Loyalists in the region, which morphed into a brutal civil war. The British high command also made the mistake of not destroying the true heart of the American Revolution, Washington's Army, and convinced themselves that tactical battlefield victories equaled strategic success. They did not. Their overconfidence in relying on what had won them battles in the past was not effectively winning them the current war.

In some capacities, the American Revolution was a guerilla war. American forces had the tactical advantage of knowing the country better than their British counterparts. Washington accepted the Fabian strategy of deception and poking and prodding the enemy, and guerilla tactics were used to harass British posts and baggage trains wherever possible. Washington's strategy of exhaustion versus a strategy of annihilation proved to be the correct course of action. The British on the other hand, could not find the winning formula. A heavy-handed approach on land and sea was only as effective as far as the soldiers could march, ships could sail, or cannon could reach. The incoherent and sometimes listless projection of power cost the Crown dearly.

We must then conclude the strategy employed by the British high command was at odds with the realities on the ground. After the surrender of the British army at Yorktown in October of 1781, war-weariness set in across the Atlantic in the British Isles. Parliament halted major military operations on the North American continent and abandoned hard-won outposts in the backcountry, taking refuge under the cover of the Royal Navy in port cities such as Charleston and New York. The failure to conceive and employ a coherent strategy cost the Crown thirteen of its New World colonies.

Further Reading

- The Long Fuse: How England Lost the American Colonies, 1760-1785 By: Don Cook

- The British Army in the American Revolution By: Edward E. Curtis and Charles Lefferts

- The Men Who Lost America: British Leadership, the American Revolution and the Fate of the Empire By: Andrew Jackson O'Shaughnessy

- Appeal to Arms: A Military History of the American Revolution By: Willard M. Wallace

Related Battles

450

1,054

1,300

587

90

1,018

155

458

330

1,135

149

868

1,111

533

182

300