Ten years before the North American colonies were in full rebellion against Great Britain, several decisions made by the British Parliament unknowingly chipped the first cracks in the relationship between the Mother Country and Her Subjects in America. Following the expensive Seven Years’ War (French & Indian War), the British Crown was heavily in debt. Parliament decided to enact new taxes on the colonies in order to bring in the needed revenue. But the sudden expectation that the colonists owed taxes to a distant governing body was miscalculated by British officials, and the seeds of discontent were planted, and a road to revolution had suddenly emerged.

King George III came to power in 1760, and unlike his predecessor, he immediately took an interest in Britain’s North American colonies. Whereas British colonial policy had long been lax, and what taxes were on the books were largely ignored or under-enforced, the new king was among those who came to see America as a rich landscape that benefited from British protection. It was long-past time they paid for such protection. At the close of the Seven Years’War in 1763, London’s territories in North America nearly tripled to encompass virtually everything east of the Appalachian Mountains and large portions of eastern Canada. The Proclamation of 1763 specifically forbid colonists from western expansion, a deal struck between British officials, Native American groups, and French diplomats. But colonists, as they ever were, continued to move westward and expanded their presence, thus expanding individual colony claims to new lands, and damaging relations with Native Americans. British Major General Thomas Gage was in charge of keeping the peace throughout the entire landscape, a tall order for a commander with troops spread out over thousands of miles. With these territorial moving parts, colonial assemblies and governing bodies remained the legislative structures in American affairs.

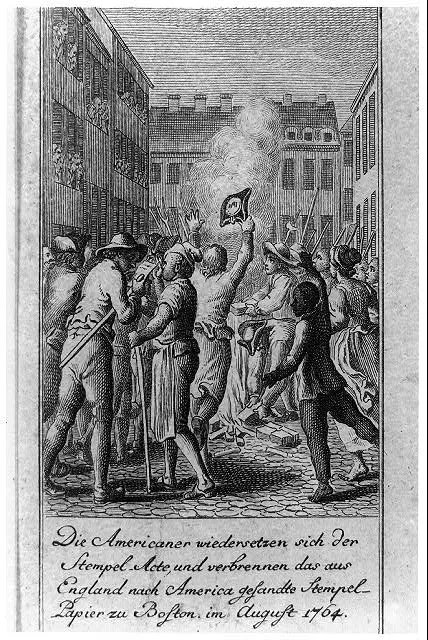

In 1764, Parliament acted on the new impulse to raise revenue from the colonies and passed the Sugar Act, an effective tax on all sugar imports from the Caribbean to North American ports. In reality, this was an updated enforcement of the Molasses Act of 1733, which had been neglected for decades due to rampant smuggling by colonial merchants. Satisfying no one, Parliament soon pushed for a more ambitious tax. This time, revenues would be raised by imposing a tax on stamps and other paper items. Effectively, no goods could be accepted or transported without using these new stamps that came with a fee, i.e. the new tax. Almost immediately, colonial merchants protested. Boston, the largest and most commercially profitable port in North America, became ground zero for pushback on the Stamp Act, scheduled to take effect on November 1, 1765.

The Stamp Act’s early genesis seemed to be of no concern for British Prime Minister George Grenville or the several colonial agents representing the colonies in London. A meeting on February 2, which included all four agents and Grenville, showed no desire on the behalf of Parliament to burden the colonies, and there was no protest among any of the agents. The debate over the proposal occurred on the floor of Parliament on February 6 and is revealing of how many among the British aristocracy viewed Americans. Charles Townshend spoke of these sentiments with,

“Now, will these Americans, children planted by our care, nourished by our indulgence until grown to a degree of strength and opulence, protected by our arms, will they grudge to contribute a mite to relieve us from the heavy weight of that burden which we lie under for their defense?”

Townshend’s words echoed a great miscalculation among the British elite. The American colonists did not see themselves as subordinate to native-born English citizens. They were English citizens. Townshend, like others, saw the Americans as second-class citizens who had long been bilking the resources of the British Empire without being asked for much in return. However, Grenville was realistic and cautious in how the measures would be received across the pond. Several exchanges between colleagues weighed how the new taxes would go over in America, including a rebuke from Isaac Barre and speeches by Edmund Burke. Nevertheless, Grenville was committed to the Stamp Act and received no serious pushback from dissenting views in London. Estimating that it would only yield about sixty-thousand pounds in one year, Grenville concluded the Americans would accept a menial tax.

In response, several colonial assemblies rallied to file petitions of grievance to London. In some cases, these assemblies produced works and words that went far beyond calling for redress. In Virginia, in a speech before the House of Burgesses, the newly-elected delegate Patrick Henry threatened the king with retaliation if the taxes were not immediately revoked, words that briefly found him liable for treason. Virginia would lead the initial charge by publishing five redresses that denounced the Stamp Act. However, two discarded measures were subsequently printed and circulated throughout the colonies. Written by Henry, one of these stated that Virginians were not bound by any laws that did not come from its own legislative body. Unintentional as they were, the published measures reverberated throughout the colonies. With only a slim number of attendees, the Virginia body was the first to reject the Stamp Act. In Massachusetts, merchants and dockworkers immediately formed the group that would become known as the Sons of Liberty in anticipation of fending off British tax collectors and enforcement.

Eight other assemblies passed similar decrees to that of Virginia, and soon a meeting was called in New York to address the concerns of the several colonial assemblies. Virginia did not attend after its assembly was disbanded by the lieutenant governor. Georgia, North Carolina, and New Hampshire also did not attend. That left eight colonies who followed Virginia’s lead in assembling a coordinated response to the Stamp Act, which has become known as the Stamp Act Congress. Held at Federal Hall between October 7 and 24, among these early revolutionaries were John Rutledge, John Dickinson, and Caesar Rodney, all of whom would go on later to important roles during the Revolutionary War. There was also James Otis of Massachusetts, becoming one of the few who boldly raised the specter of British encroachment on the colonist’s liberties. Otis was much respected by the likes of Samuel and John Adams, but feared by Massachusetts Governor Francis Bernard, who elected Timothy Ruggles to preside over the Congress. While we do not know for sure what was said during the deliberations because no journals were kept, we do know that none of the delegates there were advocating for American independence. In fact, they were specifically arguing that in order to remain loyal, obedient subjects, Parliament had to understand that taxing them in this matter would actually create more issues for both sides. The final version of what became known as the Declaration of Rights and Grievances, a series of fourteen points that went beyond addressing the Stamp Act, laid out that while intending to remain subordinate to Parliamentary authority, the colonies expected the liberties understood within the English Constitution to be afforded to them too.

With this, the colonial body agreed to remain subordinate to Parliament in all legislative matters but addressed the discontent with the Stamp Act by separating taxation between internal and external taxes. The Sugar Act of 1764 established the confusion with new taxation within the colonies, and the Stamp Act further muddied the waters by wording the legislation in a way that allowed colonial assemblies to frame the argument between these two distinct forms of taxation. How it was argued is an understanding of internal vs. external taxation. The colonists viewed external taxation as necessary regulation, such as the regulation of British trade with other kingdoms and nations. Internal taxes were not viewed as regulatory because colonists were British subjects, and in this case, internal taxes that affected the colonies could only be levied by colonial assemblies and governing bodies if they were solely enacted by Parliament. This is why colonists who framed the new taxes as internal taxes vehemently opposed them. Because these new acts to raise revenue specifically targeted goods and trade between British subjects, i.e. colonial British subjects, colonial assemblies balked that they had not been included in the legislative process. Here we see the first appearances of the rallying cry, “no taxation without representation,” a slight at Parliament for excluding membership from anyone in the colonies. Even Benjamin Franklin, an agent of the colonies in London and the most famous American in the world at the time, was steadfastly rebuffed for his desire to become a member of the House of Commons.

The resolutions were adopted on October 14 but quickly floundered as a handful of leading delegates refused to sign them, fearing they were committing treason, and should instead be sent off to the individual colonial assemblies for consideration. Copies were eventually put on ships sailing for London. The Congress dissolved on October 24, and on November 1 when the Stamp Act was to become law, several bands of Sons of Liberty throughout port towns staged mock funerals showcasing liberty being extinguished by the new taxes. With such visible agitation across the eastern seaboard, arriving British stamps were roundly seized by local authorities and kept under safeguard from mobs or were indeed stolen and destroyed by unruly citizens.

The response by His Majesty and Parliament was one of shock, bewilderment, and anxiety. Grenville, above all, had tried to mend the warring forces by reassuring the king that the colonies were not coordinating to act against his authority. But the damage had been done. Grenville, never popular with the king, was replaced with Lord Rockingham. On his way out, Grenville stubbornly reaffirmed that the colonists must obey Parliamentary authority or else. Even as the Stamp Act faced bitter opposition from the colonies, by year’s end, London was now restless with how the entire episode had gone down. At first, Parliament tried to reject receiving copies of the Stamp Act Congress’s petitions, but there was far too much opposition within Parliament to keep it from being debated. Too many English merchants were on the hook to American businesses who hadn’t paid for imported goods because they’d outright refused the stamps. This led to inflation and layoffs around coastal England. The feckless Rockingham and Parliament had done little to quell the colonial unrest. New leadership sympathetic to American liberties would emerge under William Pitt, Rockingham’s successor.

In February 1766, Benjamin Franklin spoke before Parliament in an attempt to smooth things over. While waxing poetic about commonalities that should be mended, the American reassured them that the colonists were fine with paying taxes, just not this particular tax. More to the point, the issue of internal vs. external taxes was kept vague by both Franklin and hawkish members of Parliament. Nevertheless, with the support of Rockingham, Burke, and Pitt, Parliament capitulated and repealed the Stamp Act in late February 1766, though they added their constitutional right to tax the colonies however they saw fit with the Declaratory Act. By doing so, the British were emboldening the rebel voices, giving them a reason to doubt London was serving their best interests with any new form of taxation.

What is true is that the Stamp Act Congress was only the second time in British colonial history that the individual colonies banded together to address a situation that threatened them all. Unlike the Albany Congress of 1754, this second meeting specifically targeted representation within the British government, something that had never been challenged before. And more so, the response by the British government exacerbated suspicions among rebel voices in the colonies that Parliament scoffed at the legitimacy of American colonial governments.

It’s important for us to understand that the Stamp Act crisis of 1765 was the first line drawn in the sand and that neither side backed off insinuating the first crack in the foundation that was colonial loyalty to the British monarchy.

Further Reading:

- The Ideological Origins of the American Revolution By: Bernard Bailyn

- The Long Fuse: How England Lost the American Colonies, 1760-1785 By: Don Cook

- The Stamp Act Crisis: Prologue to Revolution By: Edmund S. Morgan & Helen M. Morgan

- The Radicalism of the American Revolution By: Gordon S. Wood