Combahee River

Combahee Ferry, Tar Bluff

Beaufort/Colleton Counties, SC | Aug 27, 1782

While the events at Yorktown in October 1781 had drastically changed the winds of the war, now blowing in favor of the Americans, the war itself had not concluded. The Treaty of Paris was still being worked out overseas, and the British still occupied New York in the North and Charleston in the South. British General Alexander Leslie needed to get food for his army in Charleston, where the British retained a garrison. They were bottle-necked inside the peninsula as the Americans had been two years earlier, with the Southern Army under American Major General Nathanael Greene surrounding him. Seeking a temporary cease-fire, Leslie asked Greene if he could buy food from local farmers, but Greene refused. Short on options, the British began making excursions into the Carolina Lowcountry for cattle and rice. Leslie ordered small fleets of galleys up the rivers from Charleston to raid the plantations for food. Wanting to stop these raids, Greene set up posts along the rivers and at ferry crossings to prevent British ships from bringing supplies back to Charleston.

On August 26, a fleet consisting of a sloop of war, three galleys and three brigantines filled with British soldiers, along with ten empty sloops and galleys headed up the Combahee River to seize provisions brought by farmers to the various landings. The British troops landed undetected near Combahee Ford. Greene received word of these initial movements, and dispatched a mixed army of light infantry and cavalry under the command of Brigadier General Mordecai Gist to build a breastwork at Cheeha Neck to bombard British vessels as they backed down the river. But Gist soon discovered that the British foraging party under the command of Major William Brereton had already beaten his men to the Combahee Ferry. Gist sought to employ his 300 Continental light brigade troops to march to the relief of the rice plantations and issued orders to “strike at them whenever you meet them.” A British covering force of 140 men of the 64th Regiment and a few volunteers from the 17th Regiment formed to protect the rest of the expedition alighting to their boats. Gist’s men could not cross the river and get the British soldiers because of the enemy vessels anchored in the river. The British could not get to the supplies on the north bank due to Gist’s men. The two sides were at a stalemate.

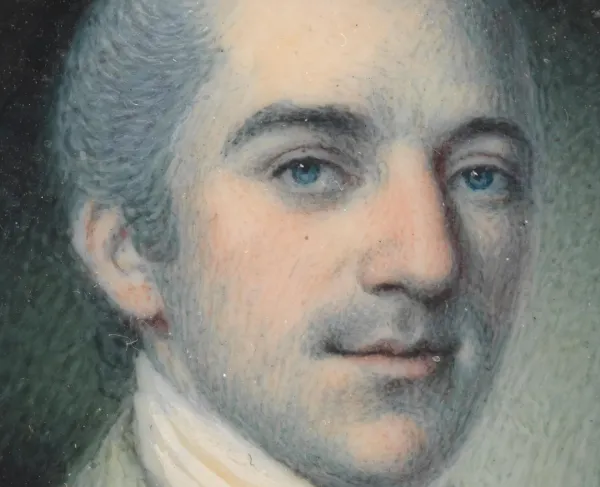

Lieutenant Colonel John Laurens, sickly bedridden near Charleston, headed to the Combahee Ferry. He had recently arrived to serve in Greene's army, having stormed Redoubt 10 at Yorktown and been head of the negotations to surrender that followed. He arrived on August 26 and requested command of the detachment Gist was planning to send across the river to intercept the British with while he remained along the water to guard the rear. Gist gave Laurens command of the small force, and sent him to Cheeha Neck to take his Light Infantry and set up his single howitzer at Fields Point, more than a dozen miles below Combahee Ferry. With Laurens were Captain William McKennan and fifty Delaware Continentals, some Virginia cavalry, and a howitzer under the command of Captain James Smith. British Major William Brereton had been informed by spies of the Patriot’s intention to place the howitzer at Cheeha Neck. He landed a force of infantry from the 17th and 64th Regiments, along with a detachment of Provincials, to ambush Laurens and his men. Back near Combahee Ferry, Gist’s advance lookouts detected the British leaving at 4:00am on August 27, to which Laurens was unaware. Gist hurried to Cheeha Neck with 150 infantry and cavalry and sent a warning to Laurens that the British were moving.

Laurens rose at 3:00 a.m. with the intent of taking the fight to the British. One of his attributes had been his willingness to put himself in harm’s way. He had shown bravery on the battlefield numerous times, receiving the wounds to prove it. His overzealous nature won him respect, but it also showed a recklessness to engage the enemy whenever he could. Accounts differ over how the skirmish began. It appears they had received Gist's warning of a possible ambush. Whether Laurens pushed to attack on his own command or was forced to attack from spotting the British troops in the high grass on his approach is unknown. However it began, Laurens called for a charge against the superior British force without waiting for the arrival of Gist’s nearby reinforcements. Captain McKennan later observed that Laurens “could not wait until the main body of the detachment would arrive, but wanted to do all himself, and have all the honor.” As the Americans scrambled forward, the first volley from the British proved disastrous. Laurens fell from his horse mortally wounded and Captain James Smith lay dying as well. Laurens had led his men in a double envelopment and half of his men were killed or wounded. The 64th Regiment captured the Patriot howitzer and its crew. The outnumbered Patriot’s force was easily repulsed.

Gist’s task force did arrive, and the British were driven back and took shelter in a log breastwork they had previously erected. The Patriots attempted to dislodge the British but were unsuccessful due to the firepower of the captured howitzer. Gist’s cavalry was unable to maneuver sufficiently. Under covering fire from their vessels, the British were able to withdraw, leaving Gist with nothing but a few horses. The British casualties were one man killed and seven wounded.

Gist’s mission to protect the rice plantations and drive the British away was semi-successful. The British moved to forage in the Lowcountry around Beaufort. Gist took his army and proceeded to Port Royal Ferry to block the British there. On September 2, they were successful in driving back the British foraging party, ending Brereton’s push through the swamps of the Lowcountry.

Greene made a report from his headquarters at Ashley Hill Plantation: “With a part of light infantry, gallantly attacked a body of the enemy, not less than 500, who had landed from their shipping in Cumbuhee River (sic); and it is with great regret I inform you, that before Gen. Gist, with the Light Infantry, could possibly arrive to his assistance, Lt. Col. Laurens’s party was repulsed, and Col. Laurens killed, together with two Officers and 24 non-commissioned Officers and Soldiers killed, wounded, and missing.”

Alexander Hamilton, who considered Laurens his best friend, wrote to Greene,“I feel the deepest affliction at the news we have just received of the loss of our dear and [inesti]mable friend Laurens. His career of virtue is at an end. How strangely are human affairs conducted, that so many excellent qualities could not ensure a more happy fate? The world will feel the loss of a man who has left few like him behind, and America of a citizen whose heart realized that patriotism of which others only talk. I feel the loss of a friend I truly and most tenderly loved, and one of a very small number.”

The site of Laurens's final battle was recently discovered through the efforts of our partners at the South Carolina Battleground Preservation Trust. On November 6, John Adams forwarded to Henry Laurens, the father of John Laurens, the resolution of the Continental Congress requiring Laurens’ attendance at the Revolutionary War peace negotiations. Adams enclosed word of John’s death, writing “I know not how to mention, the melancholy Intelligence by this Vessell, which affects you So tenderly.”

Similarly, George Washington wrote, "The Death of Colo Laurens I consider as a very heavy misfortune, not only as it affects the public at large; but particularly to his Family, and all his private Friends and Connections, to whom his amiable and useful Character had rendered him peculiarly dear."

If we are to learn one thing from this small skirmish, it should be that bravery and ambition do not guarantee success in the face of battle, especially in an operation that could have been better executed from the commanding officer. Skirmishes like the one on the Combahee River often get overlooked by Revolutionary War biographers because it took place after Yorktown; therefore the events seem moot in comparing them to the battles and skirmishes that led up to Cornwallis’ defeat. By all accounts, the assault was unnecessary and costly for the Americans, who gained nothing from the offensive operation, and who lost one of the war’s most promising junior officers in John Laurens. A rarity in the Continental Army at the time, John Laurens was young, ambitious, well-liked and ahead of his time in what would become known as an abolitionist in the years ahead. It was one of his greatest missions to arm slaves to the American Cause and inspire manumission amongst the South Carolinian plantation gentry, who roundly rejected his proposals. Who’s to say what kind of life Laurens might have led in the years following the war, and what impact he might have had on the direction of slavery in the country? What can be said by reading the reactions of everyone in the army at the news of his death is that most felt him a rising talent wasted by the theaters of war.

Related Battles

21

8