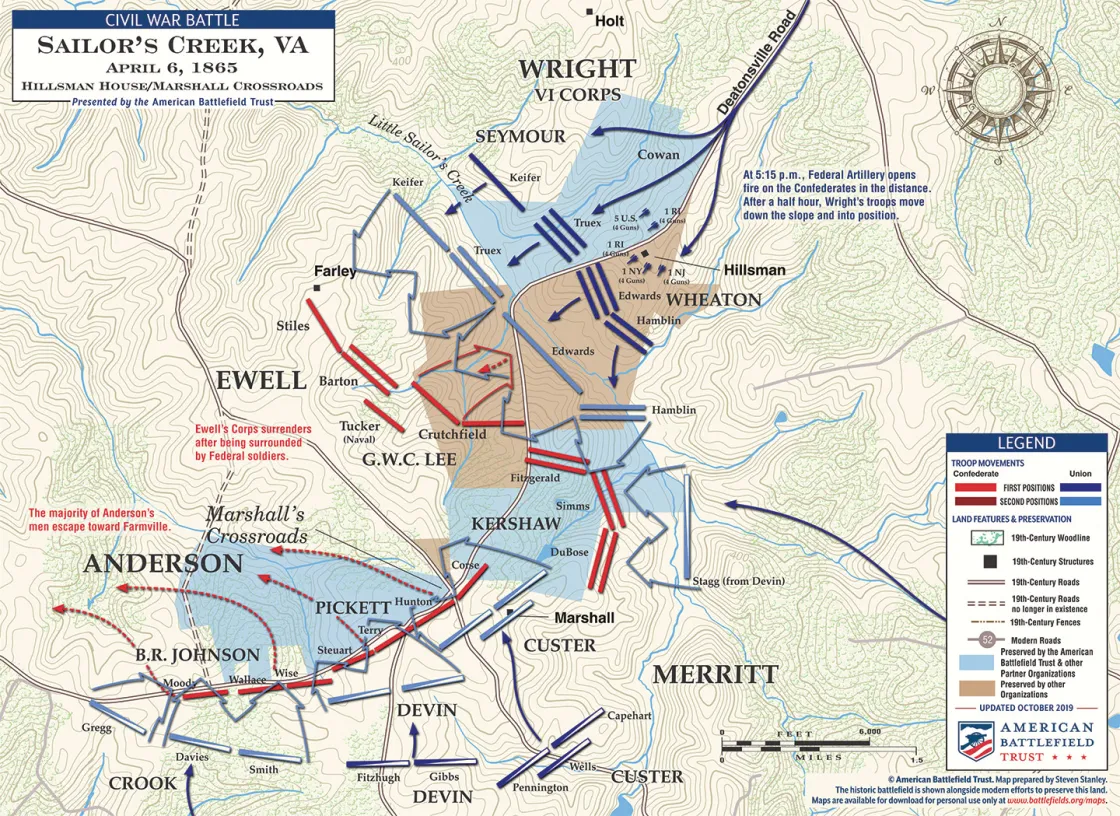

Sailor’s Creek | Hillsman House/Marshall Crossroads | Apr 6, 1865

On the rainy morning of April 6, 1865, skirmish fire announced that Gen. Andrew A. Humphreys' Union II Corps had spied Robert E. Lee’s westward movement and was now in pursuit. At the same time, Union General Phil H. Sheridan’s cavalry rode parallel to Lee's line of retreat, launching hit-and-run strikes on the Rebel column. Confederate troops commanded by Generals Richard H. Anderson and Richard S. Ewell halted at Holt's Corner to fend off the Federal attackers, thus creating a two-mile gap between Anderson and the nearest friendly unit. General George A. Custer thurst his horsemen into that gap, netting a number of artillery pieces in the vicinity of Marshall’s Crossroads. Making matters worse, Ewell caught sight of another Federal corps—Horatio Wright’s VI Corps—approaching from the east. With Yankee cavalry blocking the road to Farmville and infantry nipping at its heels, a sizable portion of Lee’s army was caught in a vice that was threatening to crush them.

Two divisions of Wright’s Corps—those of Truman Seymour and Frank Wheaton—arrived on the farm of James Hillsman at around half past four. Some 1,100 yards away, on the other side of the stream was Ewell’s force. Following orders from Phil Sheridan, Wright deployed twenty pieces of artillery in front of the Hillsman house and, at 5:15 PM, proceeded to shell the Rebel force. Unfortunately for Ewell, Confederate ordinance was in the wagon train with Gordon; the Confederates had no artillery with which to counter Wright’s bombardment.

After a thirty-minute cannonade, Wheaton’s division stepped off from the Hillsman farm and waded into the rain-swollen waters of Little Sailor’s Creek. Once on the other side, the Federals dressed their lines and continued their assault. Ewell’s defenders let loose a volley that staggered a portion of the attacking force, sending them bolting to the stream for cover. Confederate Col. Stapleton Crutchfield seized this opportunity and led an impetuous counterattack spearheaded by his heavy artillery battalions. These artillerymen acting as infantry became embroiled in savage hand-to-hand combat that claimed the life of Crutchfield, who was shot through the head. Union artillery came up in support and canister drove the Confederates back to their lines. By now Seymour’s Federals had also crossed the stream and were advancing on Ewell’s left. The pressure of Seymour’s and Wheaton’s attacks was too much for the Confederates to bear. After another brutal melee, Ewell’s men began to surrender.

At Marshall’s Crossroads, Anderson was faring no better. General Wesley Merritt’s Union cavalry pressed the Confederates on both flanks. Custer ordered a series of mounted assaults on the Confederate left division while George Crook’s dismounted attacks put pressure on Anderson’s right. Custer’s horsemen eventually broke through the Confederate line and Anderson’s men began rushing for the rear or surrendering. Watching the battle from a distant knoll, Robert E. Lee was heard to exclaim, “My God! Has the army dissolved?”

On the evening of April 6, Phil Sheridan wrote of his success to Grant saying, “If the thing is pressed I think that Lee will surrender.” When word of this reached Abraham Lincoln, the president responded, “Let the thing be pressed.”

Related Battles

1,150

8,830