Matthew Perry

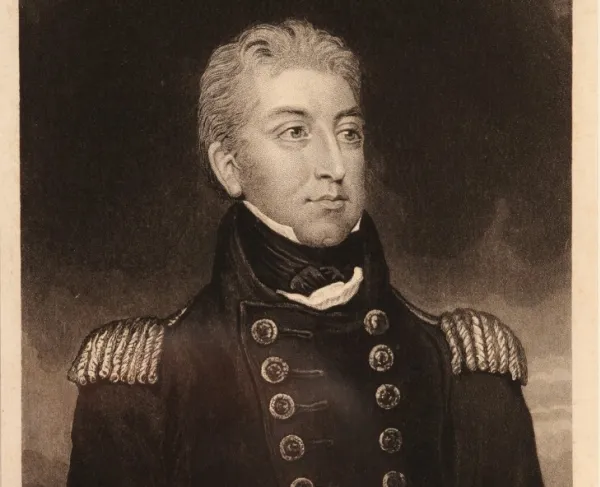

Matthew Calbraith Perry, the “Father of the Steam Navy,” was born in Newport, Rhode Island, on April 10, 1794. Continuing his family’s long maritime history, Perry enlisted in the U.S. Navy at the age of fourteen. He briefly joined the crew of the schooner Revenge under the command of his brother, Lieutenant Oliver Hazard Perry (the future hero of the Battle of Lake Erie), but after its sinking in a storm, he was reassigned as a midshipman on the USS President. On May 16, 1811, Perry was aboard the President when it engaged the HMS Little Belt, an incident that contributed to deteriorating Anglo-American relations.

At the outbreak of the War of 1812, the President attempted to intercept the HMS Belvidera, but a long chase ended only in a misfired cannon whose explosion broke Perry’s leg. Unlike his brother, Matthew Perry did not see much combat during the war. In the spring of 1813, Perry was promoted to an acting lieutenant but got stuck in New York due to the British naval blockade. During his time in the city, he met Jane Slidell. The couple married on Christmas Eve, 1814, and in the following years had ten children

Starting in 1819, Perry began nearly fifteen years of naval service around the globe, protecting American commerce and interests. Serving on the USS Cyane as first lieutenant, he escorted the first colonization mission to Liberia in 1820 and patrolled the West African coast to stop Americans engaged in the slave trade (the U.S. banned the trade in 1808). On the USS Shark, he returned the next year to help establish Monrovia. On his way back to the United States, Perry was tasked with establishing control of Key West after the acquisition of Florida that same year. Perry joined the USS North Carolina in 1825 and headed to the Mediterranean to patrol against pirates and grow trade with the Ottomans. With only a brief diversion to convey the U.S. Consul to Russia in 1830, Perry spent nearly eight years in the Mediterranean. On the seas, he gained a reputation as a strict disciplinarian, earning the nickname “Old Bruin.”

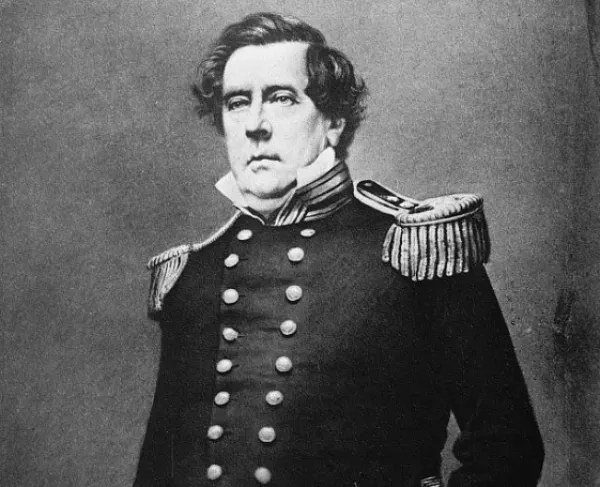

Finally returning home for an extended period in 1833, he became involved in naval reforms and innovations at the New York naval yards. Recognizing the need for sailors, he established the Naval Lyceum and the apprenticeship system. Perry also advocated for incorporating steam power into the navy, showing its value with the building of the Fulton. To care for these new steamships, he created a navy steam corps of engineers. After becoming a captain in 1837, he was promoted to commodore in 1841, commander of the New York Navy Yards.

Perry returned to the open ocean in June 1843 when he became the commander of the Africa Squadron. Tasked with enforcing the Webster-Ashburton Treaty, Perry tried unsuccessfully to stop Americans still engaging in the slave trade. Returning to the U.S. in 1845, he helped Secretary of the Navy George Bancroft establish the curriculum of the new Naval Academy in Annapolis.

Just as the Mexican-American War erupted in 1846, Perry assumed control of the USS Mississippi. He led a small fleet to capture Frontera in October and would have captured Tabasco if General Juan Batista Traconis had not advocated for a ceasefire for humanitarian reasons. Perry would later capture the city in June 1847. In the meantime, Perry helped capture Tampico and Carmen. Returning to Norfolk, Virginia, to repair the Mississippi, he secured a letter from the Secretary of the Navy to assume command of the Home Squadron, which, under him, helped in the siege and capture of Veracruz in March 1847 and Alvarado and Tuxpan in April.

After the war, the United States’ new extensive Pacific coast drew greater interest in trade with Asia. President Millard Fillmore ordered an expedition under Perry to open American trade with Japan, which had been isolated for 200 years. Perry assumed control of the East India Squadron in January 1852 and began planning the mission, leaving the United States on November 24, 1852, with the largest naval force ever sent overseas.

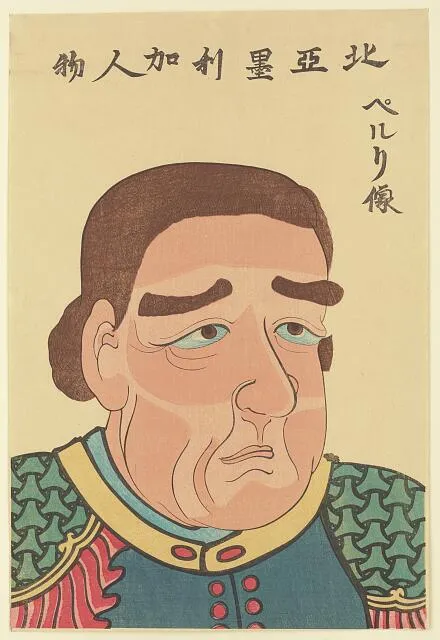

Commodore Perry sailed into Edo (Tokyo) Bay on July 8, 1853. Japanese attempts to stop the American ships were repelled. After attempts to diplomatically divert the Americans to Nagasaki––the only port open to foreigners––failed, Japanese officials acquiesced to Perry’s demands of delivering a ‘friendly letter’ from Fillmore to the emperor. On July 14, Perry disembarked his ship at Kurihama (near Uraga at the mouth of the bay) to American fanfare. He told the Japanese he would return the next year for a response to the letter.

The death of the Shogun and dysfunction in the Tokugawa regime left Japan unable to effectively respond to Perry upon his return on February 13, 1854. After a heated exchange, the Japanese negotiator, Daigaku-no-kami Hayashi, agreed to meet Perry at Kanagawa, near modern-day Yokohama. First meeting on March 8, the two men spent nearly three weeks debating particulars, exchanging gifts, and sampling each other’s cultures. The Treaty of Kanagawa, signed on March 31, opened the ports of Shimoda and Hakodate to American ships and gave the United States a favored-nation status in the Japanese courts, among many other provisions. Perry signed the Loochoo Compact in July with the Ryukyu to also open Okinawa to American trade.

Perry returned to the United States on January 11, 1855, to official celebrations for opening Japan. The public, however, not seeing diplomatic value in Japan, welcomed him with only lukewarm enthusiasm. It was not until the publication of his Narratives of the Expedition of an American Squadron to the China Seas and Japan the next year that Perry got public recognition. Unfortunately, after years at sea in inclement weather, his health quickly declined. Perry passed away on March 4, 1858, from rheumatic fever. He was initially buried in St. Mark’s Church in New York but was moved to Island Cemetery in Newport on March 21, 1866, where his widow commissioned a monument for him in 1873.