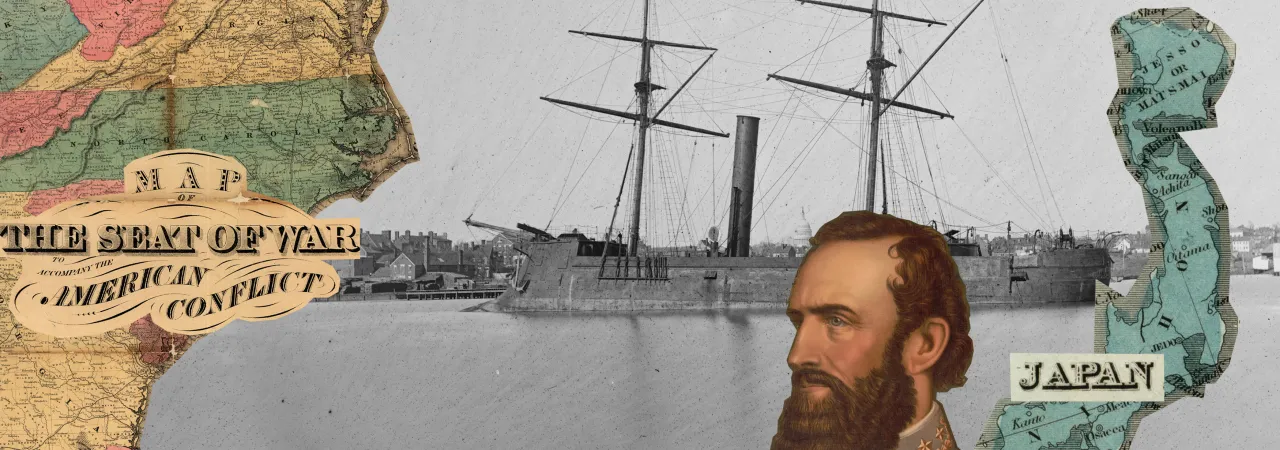

In the early days of 1865, French shipbuilder Lucien Arman sold the Confederate Navy one of the deadliest vessels ever built up to that point in history. The Confederates named the ship the CSS Stonewall, and their brief time at its helm marked the start of 23 years of service on the shores of three continents.

The Stonewall had its first triumph before even setting off for the Americas, when its new Confederate crew stopped in Spain for much-needed repairs after a storm. During the Stonewall’s seven weeks docked in Spain, Union representatives continuously lobbied the Spanish government to cease the repairs and assigned two ships to monitor the situation. Yet, when the renovated Stonewall was finally ready to cross the Atlantic, the Union ships, intimidated by the powerful vessel, reluctantly allowed it to pass without a fight.

Upon arrival in Havana, Cuba, the CSS Stonewall’s captain received some troubling news: the Union had won the war. He opted to sell the Stonewall to Spanish colonial officials for $16,000 – enough to pay his crew and see everyone home. The Spanish officials quickly sold the vessel to the U.S. government for around the amount they’d paid for it. The ship then sat in the Washington Navy Yard in the nation’s capital for several years before catching the eye of Japan’s feudal lords, the Tokugawa Shogunate, who hoped to hold onto power by upgrading their navy. The Shogunate purchased the Stonewall, but by the time the ship saw combat in Japan, it was actually serving under the Shogunate’s adversaries, who had successfully taken control of the country. The ship was renamed the Kōtetsu, then, later, the Azuma, and it served Japan’s new Meiji government until it was retired from the Japanese fleet in 1888.

So, what was it about the CSS Stonewall that inspired such fear and admiration? Here’s a breakdown of what made this ironclad so exceptional for its time.

The Armor

Perhaps the most innovative characteristic of ironclads (and the inspiration for their name) was the armor that protected them from enemy artillery. Well-constructed ironclads could withstand tremendous fire, rendering previously deadly weapons practically useless and upsetting the ancient naval axiom that forts are stronger than ships. The Stonewall featured iron plating with thickness ranging from 3.5 to 5-inches extending a full 5 feet below the waterline, as well as some 5-inches of iron armor in the front and back of ship that offered extra protection to artillery and crew.

The Ram

The Stonewall was born in a fleeting period when armored vessels had become the pinnacle of naval innovation and armor piercing shells hadn’t been invented yet. Rams, an ancient naval technology, made a brief comeback as designers realized the increased maneuverability of a steam engine combined with defensive armor meant one ship could get close enough to smash into and sink another – even another ironclad. In fact, it’s likely that the wood-hulled Union ships guarding the Stonewall during its stop in Spain declined to engage for fear of this prospect. The Stonewall’s ram created a menacing impression but also caused the vessel to handle clumsily when traveling at speed.

The Steam

The age of ironclads would not have been possible without innovations in steam propulsion to allow vessels to navigate with such heavy armor. The Stonewall itself was sail-assisted, allowing it to conserve coal over long distances by using sails when conditions were right. Twin screws and twin rudders allowed for precise steering, including rapid turning, in calm waters.

The Guns

While the Stonewall’s guns were not its most impressive feature, they were nothing to scoff at either. The vessel carried two 70-pounder Armstrong guns, fixed armored turrets containing muzzle-loading pivot guns that could be pointed out of any of several gun ports, and one massive, turreted 300 pounder. At the start of the ship’s tenure at the head of the Imperial Japanese Navy, the newly renamed Kōtetsu famously repelled a surprise attack at the Battle of Miyako Bay largely thanks to a Gatling Gun, a precursor to the machine gun.

Ultimately, Lucien Arman’s remarkable feat of engineering helped shape the fate of a nation – just not the nation it was originally designed for. The vessel was cutting edge even by Western standards, but as Japan’s first ironclad it proved a gamechanger and kingmaker, suppressing several rebellions and serving the Meiji Navy for nearly two decades. By the time this ship of many names retired in 1888, it had helped steam Japan right into the modern era, with all the progress and strife that era would bring.

If the story of the CSS Stonewall leaves you wanting more, watch this In4 video for more about naval technology in the Civil War, then learn more about Navies in America’s Wars.