Naval Operations in the Mexican-American War

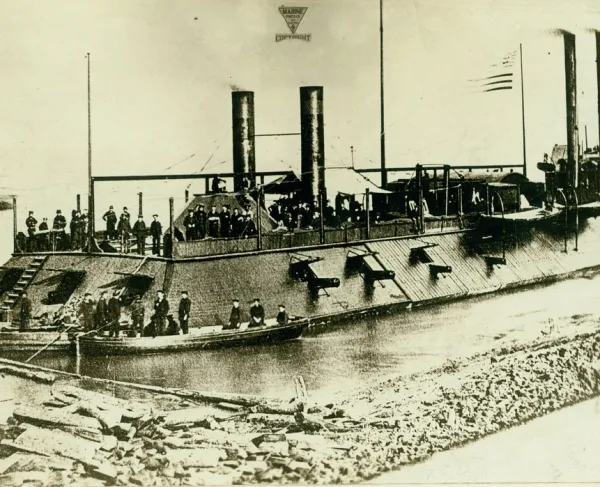

Commodore Matthew C. Perry’s flotilla securing the coastline and rivers of Tabasco in 1847.

When hostilities commenced between the United States and Mexico in April 1846, most believed the conflict would be predominately fought on land. Fighting erupted over the disputed common border in Texas while Americans already coveted Mexico’s northwestern lands. Despite most participants focusing on ground combat and armies' progress, the Mexican-American War quickly became one where naval power was crucial for achieving war aims.

After the declaration of war, the United States Navy struggled to implement ongoing industrialization. Of America’s 73 warships, revenue cutters and supporting logistics vessels, only eight were steam-powered paddle-wheelers, with engineering machinery exposed to enemy fire. Naval officers were professionally trained through a system of mentorship at sea, not in a formal academic setting. Most sailors had years of training afloat, but little combat experience. Despite these shortcomings, the American Navy was a professional force with decades of experience deploying globally, and it significantly outmatched Mexico’s fleet.

Mexico also possessed a professional navy, though it was smaller than that of the United States. All its 14 ships were sail-powered and often more lightly armed than American warships. Despite these comparative shortcomings, Mexico’s sailors had spent decades fighting for independence, crushing internal rebellions and guarding both their Atlantic and Pacific coastlines.

The United States Navy’s first goal focused on blockading Mexico’s coast. This proved troublesome, due to the American’s fleet limited size and Mexico’s vast coastline. Commodore David Connor’s Home Squadron assigned warships to watch Mexico’s principal ports in the Gulf and Bay of Campeche: Tampico, Veracruz and Alvarado. By April 1846 when the war began, Connor already had four frigates, four sloops and three brigs patrolling these ports with sailors “kept constantly exercising with small-arms.” The warships maintained a precarious logistics situation, however, sailing to Pensacola, Florida, to resupply.

After land hostilities began, Connor also supplied and supported Major General Zachary Taylor’s army near Matamoros, on the Rio Grande. USS Potomac assisted in capturing Tampico, while Commodore Matthew C. Perry commanded a flotilla led by the steam frigate Mississippi that secured the Grijalva River in Tabasco by using a “landing party of marines and sailors” determined to “fight the enemy wherever he could find him.” In April 1847, most of Mexico’s Atlantic fleet was scuttled to prevent capture after being trapped in the Alvarado Lagoon, giving the United States naval supremacy in the Gulf.

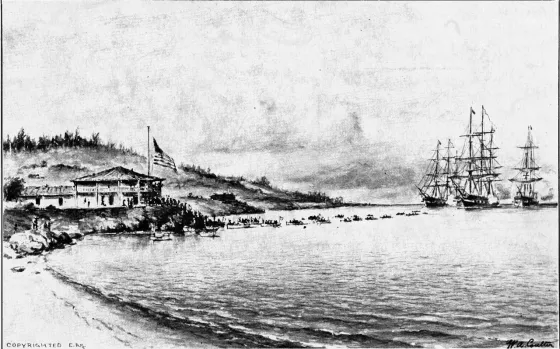

In the Pacific, American warships supported the conquest of Alta California. In July 1846, the frigate Savannah and sailing-sloops Levant and Cyane secured Monterey, California’s capital. Officers “left on shore a sufficient number of soldiers and seamen to hold possession” of the town. Savannah then secured San Francisco, while, Cyane, skippered by Commander Samuel Francis Du Pont, embarked a battalion of soldiers led by Lieutenant Colonel John C. Frémont. Du Pont anchored in San Diego, landing sailors and Marines, and took possession of the town, all while Frémont’s men engaged nearby fortifications. Du Pont reported “great joy prevailed among women and children” as Americans arrived.

In January 1847, Commodore Robert F. Stockton led an interservice force near Los Angeles. Stockton’s Pacific Squadron, including three frigates and a ship of the line, covered a landing of a division of volunteers, professional soldiers, and Marines who ultimately took control over the Los Angeles area. Stockton then acted as governor over Alta California until senior military commanders arrived.

Further down the Pacific coastline, the United States Navy implemented a blockade near Mazatlán and in the Gulf of California, with officers declaring “all munitions of war, and vessels sailing under Mexican colors, or the property of Mexicans … be considered as prizes.” Sailors and Marines also targeted Baja California Sur by assaulting defenses near Cabo San Lucas, which they occupied until hostilities ended.

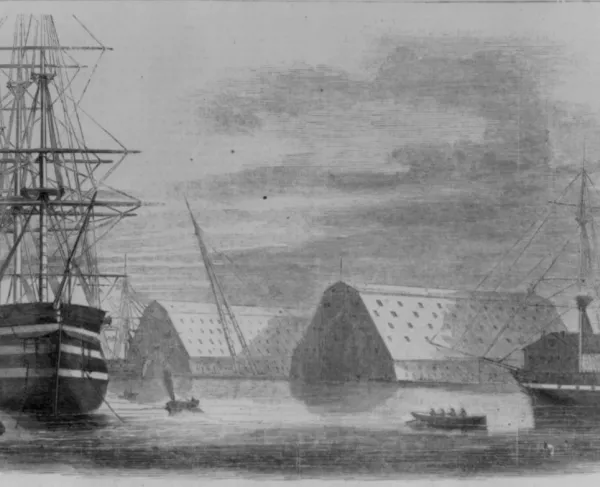

Back in the Gulf, American naval forces also supported Major General Winfield Scott’s military campaigning. Despite some officers considering Commodore Connor “too much afraid of risking his men” and lacking “moral courage,” the Home Squadron commander cooperated with Scott. Connor’s fleet, seven heavy warships backed by smaller auxiliary craft, transported Scott’s army to Veracruz. The Home Squadron then facilitated the landing of 10,000 soldiers ashore, resulting in a successful siege of Veracruz’s defenses. A siege battery manned by sailors and Marines joined military forces ashore, at one point engaging a Mexican battery also manned by sailors and resulting in a small skirmish ashore where “the two navies were opposed to each other.” Scott used the secured Veracruz as a base for marching inland while American sailors under Commodore Matthew C. Perry protected the flow of supplies, helping Scott ultimately reach and capture Mexico City, concluding hostilities.

All of Mexico’s naval forces were either lost in battle, captured by Americans, or scuttled to prevent their capture or as river obstructions. It was one element in Mexico’s larger defeat that led to significant debts and ongoing civil war in the 1850’s.

Conversely, the Mexican-American War proved a significant proving ground for the United States Navy. American officers demonstrated that their squadrons could facilitate a blockade of a weaker naval power, plan and execute amphibious activity, and support cooperative interservice operations ashore – even if most of these actions were on an ad hoc basis without formalized established doctrine. Just as with the military. From both an organizational standpoint and at the individual level amongst its officers and sailors, the United States Navy learned a great deal from the Mexican-American War that was later implemented in the Civil War.