USS Cairo (pronounced “kay-rho”) was the lead vessel of the City class of Union gunboats which were constructed for riverine service during the American Civil War. Ordered by the Union Army in August 1861, she was named for the city of Cairo, Illinois, a major Union supply base at the junction of the Ohio and Mississippi Rivers. Completed in less than six months, she was commissioned on January 25, 1862, and launched from her berth at Mound City, Illinois. She quickly entered the fight in the Western Theater, where she joined the Army’s Mississippi River Squadron, assisting Union forces in the capture of Clarksville and Nashville, Tennessee, and escorting Union mortar-gunboats during the bombardment of Fort Pillow. In an engagement with Confederate gunboats off Plum Point Bend on May 11, 1862, Cairo and her fellow ironclads staved off an attack by 8 Confederate gunboats trying to relieve Fort Pillow’s garrison.

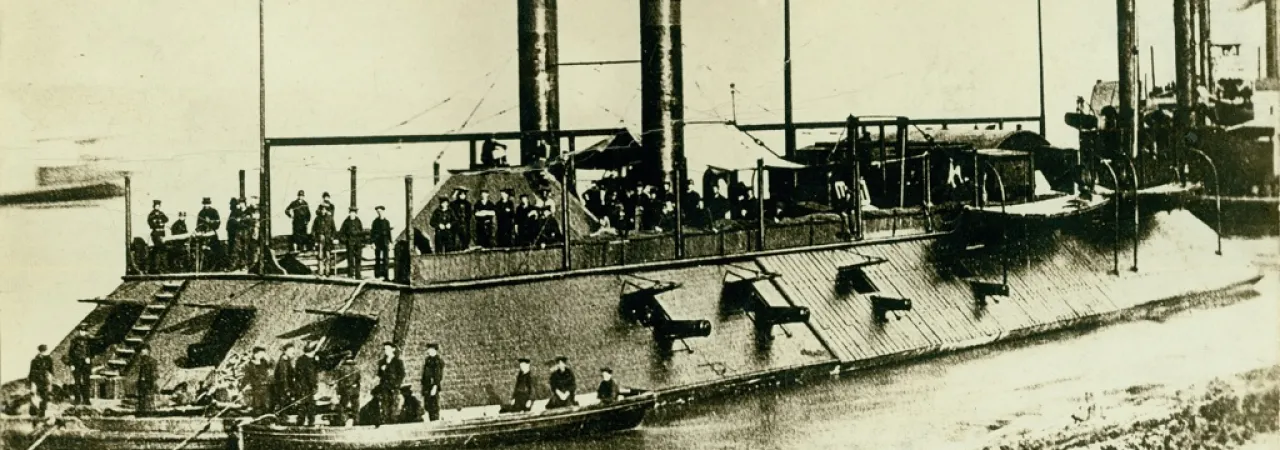

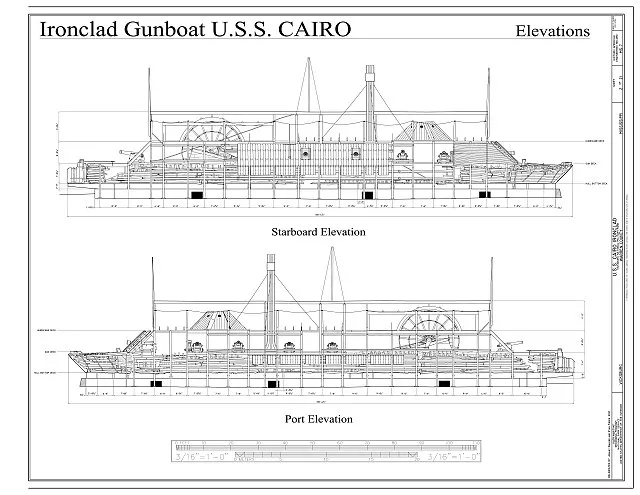

Cairo was armed to the teeth, carrying three 8-inch smoothbores (“inch” referring to the width of the shell), three 42-pounder rifles (referring to the weight of the shot), six 32-pounder rifles, one 30-pounder and finally a 12-pounder rifle. She was also clad with iron plate armor, ranging from 2.5 to 3.5 inches thick, providing adequate protection against the Confederate fortress guns she was tasked with destroying. Her rifled guns also had the penetrative power to smash through the armor of opposite Confederate ironclads in the anti-ship role. A steam engine powered by five boilers propelled a paddle wheel placed within the armored core of the ship. With this powerplant, Cairo was capable of outmaneuvering her opponents in more open waters. Her flat hull and shallow draft (that is, the area below the waterline) allowed her to operate with ease on the Mississippi River and its many tributaries.

Cairo’s crew of 159 officers and enlisted men were split into divisions which each operated one part of the ship. Firemen and boilermen kept the fires burning and steam flowing in the boilers, powering the ship. Gunners maintained and operated Cairo’s many cannons. Besides these two larger groups, smaller groups of men operated the pilothouse, steering the ship, another provided medical attention, and small groups or individuals performed administrative tasks such as purchasing supplies and paying the crew’s wages. This sophisticated division of labor allowed Union gunboats like Cairo to operate efficiently, even with the added strains of combat.

On June 6, 1862, two days after Fort Pillow surrendered, Cairo and six other Union gunboats defeated a Confederate fleet off Memphis, sinking or running ashore five of the eight Confederate ships present. These Confederate warships were “cotton-clads”, civilian riverboats with cannons installed and covered in cotton to shield them from small-arms fire. This was all the Confederates, too short of money and iron to manufacture armored warships from scratch, could muster. Two more Confederate ships were seriously damaged, and only one vessel was able to escape. This victory enabled Union forces to capture and occupy Memphis that same night.

Cairo patrolled the Mississippi for the next five months until November 21 when she received orders to join the Yazoo Pass Expedition. This was Union Gen. Ulysses S. Grant’s first attempt to encircle and capture the Confederate defenses at Vicksburg, Mississippi. Vicksburg sat atop a high ridge looming over a bend in the Mississippi River. Armed to the teeth with large cannons, even heavily-armored warships like Cairo could not safely attack Vicksburg head-on. Thus, Grant wanted to find a way through the swamps and Bayous of the Yazoo River delta around and behind Vicksburg; Union forces could then approach Vicksburg from the east, away from where the Confederate guns faced.

The bayou proved a match for Cairo and the Union riverboat flotilla. The natural impediments complimented by the placement of “torpedoes” (mines) by the Confederates rendered the route impassable to the Union vessels. That did not stop Union forces from trying to force their way through, however, by cutting down trees and removing obstacles to clear a path through the backwater. Cairo was assigned to one such mission, tasked with clearing Confederate mines from the Yazoo River. While conducting this mine-clearing operation in preparation for an attack on Haines Bluff, Cairo struck one of the mines, which was then detonated remotely via a wire by hidden Confederates watching from the riverbank nearby. The mine hit the unarmored hull of the ship rather than the armored gundeck. The explosion proved fatal for the vessel, which sank in 12 minutes, but the entire 159-man crew managed to escape.

No attempts were made to recover the ship during the war, and soon the ship’s location was forgotten. River silt buried and preserved the remains of the vessel and the artifacts inside. In 1956, National Park Service historian and World War II Marine veteran Edwin C. Bearss set out to find the USS Cairo. Studying period maps and with a magnetic compass, Bearss, assisted by Don Jacks and Warren Grabau, found the wreck beneath the silt. With the location now known, another expedition in 1960 recovered a number of artifacts, including the entire pilothouse and one of her 8-inch smoothbore cannons.

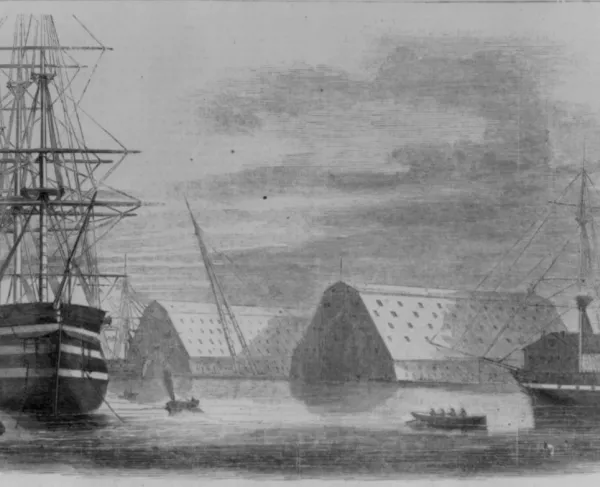

Not long afterward, the State of Mississippi partnered with the Federal Government and local authorities to raise the wreckage from the river. At first, attempts were made to raise Cairo whole, but she was damaged by the lifting cables. The decision was made to cut the ship into three parts and raise each separately. By December, 1964, 102 years after she sank, all three sections were above water and put on barges bound for Vicksburg. Restoration work was done at Ingalls Shipyard in Pascagoula, Mississippi, where her armor was cleaned and safely stored. In 1972, Congress passed a law allowing the Park Service to accept USS Cairo and put her on display in Vicksburg. Five years later, she was placed into a new concrete foundation near Vicksburg National Cemetery and a protective shelter was completed in 1980. One month later, an adjoining museum was opened to the public with artifacts recovered from the wreck on display.

Though she never fought at Vicksburg, USS Cairo remains a prime attraction at Vicksburg National Military Park, and the only surviving example of a City-class ironclad from the Civil War. Her sister ships played a critical role in the later stages of the Vicksburg Campaign, running the guns under which Cairo now rests. Now Cairo helps tell their stories and hers to many thousands of visitors each year.