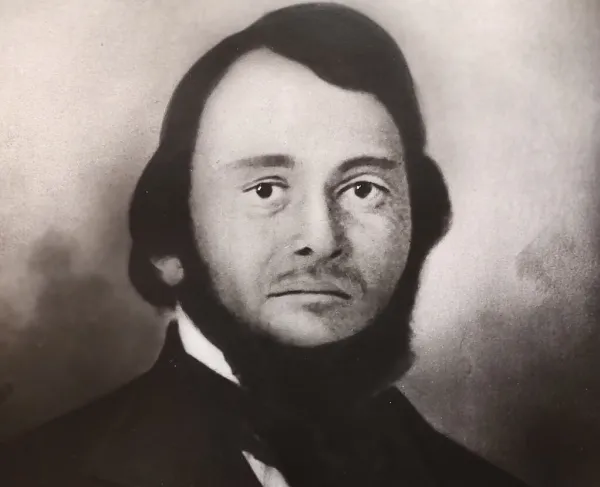

Kit Carson

Christopher Houston Carson, colloquially known as Kit Carson, was born on December 24, 1809, in Madison County, Kentucky. Less than a year later, his family moved into the newly acquired Louisiana Territory, settling near modern-day Howard County, Missouri.

Disliking his work as a saddler apprentice, Carson joined a scouting party headed to Santa Fe in August 1826. Over the next three years, he served as a cook, copper miner and interpreter on various expeditions to New Mexico. From 1829 to 1841, Carson undertook many journeys into the Rockies, California and Oregon Country that would make him famous for his mountaineering, survival and hunting skills. One such trip to the northern Rocky Mountains began in October 1833 and lasted eight years. In his autobiography, Carson described his negative encounters with Native Americans. Raiding back and forth, the mountaineers and Native tribes engaged in many skirmishes against each other, often ending brutally for the latter.

In April 1842, he returned home to Missouri where he first met Colonel John C. Fremont. The two undertook three expeditions together to survey the Oregon Trail. In a particularly dark episode, Carson and Fremont stopped a supposedly an incoming Wintu attack in California by massacring hundreds of Native Americans. The Sacramento River Massacre, as it would be called, was followed by a similar massacre further north in Klamath Lake.

Coming back from Klamath Lake to the Sacramento Valley in May 1846, Carson and Fremont discovered the United States officially declared war on Mexico. With local Anglo-American settlers in Monterrey, they sailed to San Diego and marched to conquer Los Angeles. In October 1846, as Carson headed east with messages to deliver to Washington D.C., he met General Stephen Kearny and agreed to guide his military force back to California. At the Battle of San Pasqual (near San Diego), Mexican forces outnumbered and flanked the Americans, so Kearny sent Carson ahead with requests for reinforcements. Kearny, finally reached the Pacific a few days later, securing control of Alta California for the United States. In March 1847, Carson returned to his duty of bearing information for the War Department in Washington. While meeting with President James K. Polk in June, he was appointed a Lieutenant of Rifles in the US Army and sent back to California with dispatches. Despite the Senate never confirming his appointment, Carson continued to fulfill his duties.

After the war ended, Carson settled on a ranch in Rayado, New Mexico, about fifty miles from Taos.11 In December 1853, he was appointed as Indian agent in the recently established New Mexico territory. 12 Under his new title, he dealt with affairs regarding the Apache, Mauche Utah and especially Ute. Often, these affairs turned violent as part of the long series of American Indian Wars.

As the Civil War broke out, Texans quickly moved into the New Mexican territory to secure it for the Confederacy. In May 1861, Carson resigned his post as Indian Agent, volunteering for the Union. In August, he was appointed the lieutenant colonel of the New Mexico Volunteers and, by October, the colonel. In February 1862, Carson commanded the first regiment of volunteers in the Battle of Valverde, where they acted as support for the regular infantry. After the battle, they stayed to guard Fort Craig. In late 1862, Carson and his troops were ordered to pacify the Mescalero Apache and force them onto a reservation. The especially bloody campaign was mainly carried out by Brigadier General James Carleton. Carleton then tasked Carson with doing the same for the Navajo in 1863, sending them to the Bosque Redondo reservation on the Pecos River. Having difficulty finding the tribes, Carson instead burned their villages and crops, attempting to force the Navajo to give in. On January 15, 1864, Carson succeeded, and the remaining Navajo surrendered at Canyon de Chelly, starting their long walk to Bosque Redondo. The reservation proved to have disastrous conditions, with disease and inhospitable weather killing many Navajo. In his final military engagement, Carson set out with Ute allies to protect the Santa Fe trail from Kiowa and Comanche attacks at Adobo Walls in November 1864, a battle ending inconclusively.

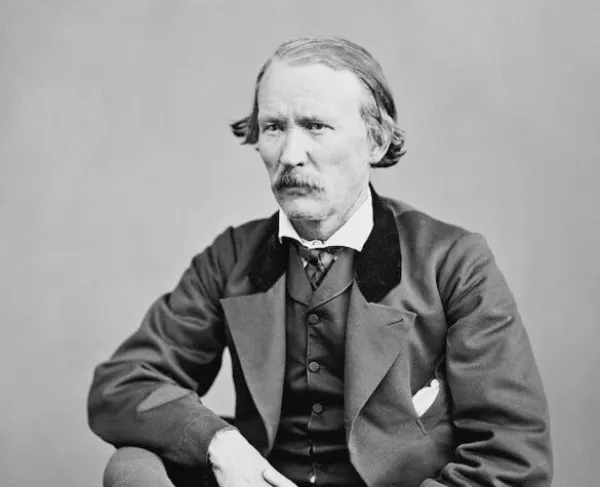

After the war, Carson was appointed a brevet brigadier general and commandant of Fort Garland in Ute territory. Later settling as a rancher in Boggsville, Colorado, his physical state began deteriorating due to an aneurysm. Carson died at nearby Fort Lyon on May 23, 1868. His body was buried near his home in Boggsville before being moved to Taos, New Mexico a year later.

Carson was married three times but only acknowledging his third wife in his memoir. The first two, Singing Grass whom he married in 1836, and Making-Out-Road in 1841, were Native women of the Arapaho and Cheyenne tribes, respectively. He married Josefa Jaramillo in 1843 in Taos, surviving her by eleven days in 1868. Overall, he had ten children: two with Singing Grass and eight with Josefa.

Both during his life and after his death, Carson was romanticized in American culture as the idealized frontiersman and mountaineer. He was the subject of paperback dime novels and later numerous movies and TV shows. Carson learned of his fame during an expedition against the Apache in 1849, where he encountered a paperback novel in which he himself was depicted as a frontier hero. More recently, however, his legacy has been subject to greater scrutiny due to his brutality toward many Native American tribes.

Related Battles

39

16

276

229