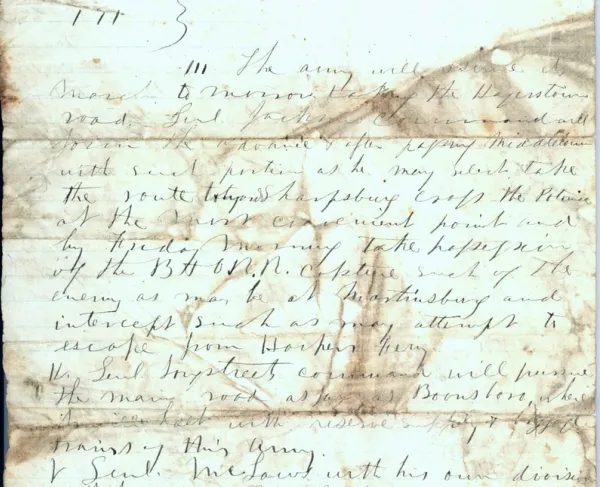

Stonewall Jackson's Triumph at Harpers Ferry

Dennis E. Frye, for Hallowed Ground

Civil War students adore facts. We read voraciously to discover them. We work aggressively to memorize them. We boast gleefully when we challenge friends and stump them. So, here are some not-so-well known facts to add to your personal arsenal:

Fact: The largest surrender of United States forces during the Civil War occurred at Harpers Ferry.

Fact: The biggest engagement of the Civil War in present-day West Virginia happened at Harpers Ferry.

Fact: The Battle of Antietam never would have transpired without the preceding Confederate victory at Harpers Ferry.

REVELATIONS?

When not reveling in facts, Civil War aficionados glory in debate. We never cease discussion on “the turning point” of the war. We endlessly argue about who was the best and worst general. And we hopelessly explore the enduring question – what would Stonewall Jackson have decided on the first day of Gettysburg?

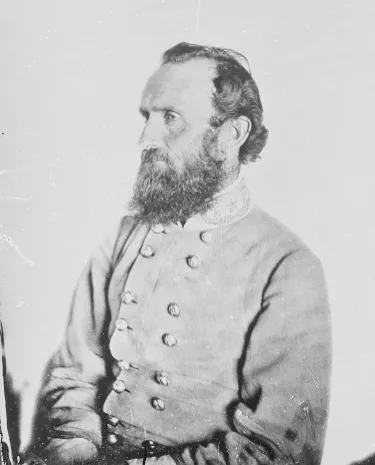

Speaking of Stonewall Jackson, let’s add to the debate. Consider this – Stonewall Jackson’s most complex and most complete tactical victory occurred at Harpers Ferry.

Blasphemy, you shout! What about Chancellorsville? What about First Manassas? What about Second Manassas? What about … Before dismissing Harpers Ferry as Jackson’s greatest battlefield triumph, ponder these questions: First, where else did Jackson face such natural obstacles? Second, where else did Jackson face a stronger enemy position than his own? Third, where else did Jackson achieve greater battlefield results?

One reason you’re perplexed is this – Harpers Ferry has received little notice from military historians during the first century plus two score years following the Civil War. Remembered primarily for its John Brown notoriety, Harpers Ferry virtually has vanished into the shadow of Antietam. In the earliest Maryland Campaign study, written by Francis Palfrey and published by Scribner’s in 1882, Palfrey devotes a paltry four pages to a three-day operation at Harpers Ferry. Conversely, Palfrey dedicates fifteen pages to the one-day Battle of South Mountain and 94 pages to the one-day action at Antietam.

No explanation exists for Palfrey’s prejudice against the Harpers Ferry story. Perhaps the former Union officer was embarrassed by the Federal disaster, and chose not to write about Stonewall’s brilliant victory. Or perhaps he was influenced by an 1862 United States military commission that declared the Harpers Ferry commander’s “incapacity, amounting to almost imbecility, led to the shameful surrender of this important post.”

Branding the Union commander with incapacity and imbecility has veiled Jackson’s extraordinary accomplishments at Harpers Ferry. Some have argued the Federal commandant was drunk, while others contend that the disenchanted and disenfranchised post commander committed treason against his disrespectful country. These brash claims further diminish the tactical brilliance of Jackson at Harpers Ferry. The accepted platitude, unchallenged by historians for generations, is that Jackson faced a weak and irresolute enemy who simply crumbled before the presence of the Mighty Stonewall. Nothing is further from the truth.

ROBERT E. LEE SUMMONED JACKSON to discuss a critical mission. The Confederate army had settled near Frederick, Maryland, at the outset of the second week of September, 1862, only forty miles northwest of Washington. Here Lee faced an unexpected problem – not from the Union capital, but to his rear where 14,000 Union soldiers at Harpers Ferry and Martinsburg threatened his avenue of supply and communication back into Virginia. “I have no doubt they will leave that section,” Lee confidently informed President Jefferson Davis on September 5. Four days later, however, not one bluecoat had departed from the Shenandoah Valley.

Nor would they. General-in-Chief Henry W. Halleck determined to maintain a strong Federal presence in the northern Valley. “Our army is in motion,” Halleck wired the Harpers Ferry commander on September 7. “It is important that Harpers Ferry be held to the latest moment.”

Frustrated by the Union army’s failure to cooperate, Lee turned his full attention toward Harpers Ferry. Further delay in opening his supply route was intolerable. The Federals holding the Valley must be moved or eradicated. Harpers Ferry, never intended as a target in Lee’s first invasion of the North, suddenly became the target.

To eliminate the Harpers Ferry problem, Lee developed a plan. He would divide the army into four columns – three would converge upon Harpers Ferry, seizing the three mountains surrounding the town. The fourth column would move to Boonsboro, 15 miles north of Harpers Ferry, where it would await the return of the Harpers Ferry expedition.

Lee labeled his divide and conquer plan as Special Orders 191. Although splitting and scattering his army, the Confederate commander anticipated minimal danger from the enemy. The Federal army had been acting defensively since the invasion of Maryland, spreading like an amoeba to cover all approaches to Washington and Baltimore. Lee expected his foe to remain cautious and non-aggressive, permitting ample time for his army to complete the Harpers Ferry operation and to reunite.

To execute the Harpers Ferry investment, Lee selected Stonewall Jackson.

No other officer in the Confederate army could surpass Jackson’s knowledge of Harpers Ferry. In the spring of 1861, with the war in Virginia less than two weeks old, Jackson’s first field assignment was commander of the post at Harpers Ferry. Applying the studious and methodical approach he had developed as a West Point student and later practiced as a professor at VMI, Jackson analyzed and memorized the Harpers Ferry terrain, and theorized about attack and defense. In fact, “Old Jack” had tested his theories while directing a sortie against Harpers Ferry during his famous Valley Campaign in late May, 1862.

To accomplish his mission – eradicate the Union presence in the rear of the Confederate army – Lee assigned six of his nine divisions to the Harpers Ferry operation. Two thirds of the Rebel army, or approximately 26,000 men, began tramping toward Harpers Ferry on September 10. For General Lee, Harpers Ferry was not a sideshow, but the show.

Stonewall Jackson faced a complex challenge. He commanded three diverging columns, approaching Harpers Ferry from three different directions, with three separate targets (mountains) as his objectives.

Further complicating the plan was geography. Two of the columns had to re-cross the Potomac River, without bridges or pontoons. In addition, Jackson’s wing had to scale two mountains – Catoctin and South Mountain – en route to the river. Even upon reaching Harpers Ferry, the Potomac and Shenandoah Rivers truncated the Confederates. Special Orders 191 required an extraordinary level of coordination, communication, and convergence. Would it work?

Lee required Jackson to make it work. The future of the invasion depended upon success at Harpers Ferry. Failure was not an option.

Jackson exuded confidence. At 5 a.m. on September 10, his column of 14,000 men began marching west out of Frederick on the National Road. Three days later, after a circuitous trek of 57 miles over two mountains and the Potomac (via Boonsboro, Williamsport, and Martinsburg), the head of Jackson’s wing approached Harpers Ferry from the west, debouching on School House Ridge. Meanwhile, John G. Walker’s division had secured Loudoun Heights from the south, and by late afternoon on the 13th, Lafayette McLaws had gained control of Maryland Heights to the north. The Federals were trapped. Indeed, 14,000 Union soldiers were surrounded, but not surrendered.

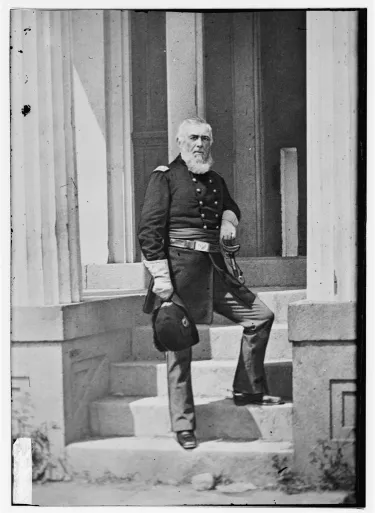

Colonel Dixon Stansbury Miles, the Harpers Ferry commander, had specific orders: “Be energetic and active, and defend all places to the last extremity,” demanded a September 5 dictate from Miles’s superior, Major General John G. Wool. “There must be no abandoning of post, and shoot the first man that thinks of it.”

Colonel Miles was no neophyte. A 42-year veteran of the army, the native Marylander was a West Point graduate who had earned three brevets during the Mexican War. He had ascended to colonel of the 2nd United States Infantry during the antebellum period, distinguishing himself as one of only ten regimental infantry commanders in the Regular Army, outranking Robert E. Lee.

George McClellan had assigned Miles command of the “Railroad Brigade” in March, 1862, after a court of inquiry had cleared Miles of drunkenness charges at the First Battle of Bull Run. Miles then established his headquarters at Harpers Ferry, where he performed the duties of a department commander, using his 6,000 – 15,000 men to patrol 380 miles of railroad, stretching from Washington to Baltimore to the South Branch of the Potomac. Miles also had combat experience, engaging in the defense of Harpers Ferry during Jackson’s Valley Campaign.

Although surrounded by Jackson’s men on September 13, Miles refused to wave the white flag. Confederate infantry had seized the crests of Maryland and Loudoun Heights, but Miles persevered – the high ground was lost, but the Potomac and Shenandoah rivers separated his command from the mountain tops, making it improbable that enemy infantry would attack him, and nearly impossible for Rebel small arms fire to reach him.

Still, Miles was concerned about his predicament. On the night of the 13th, he ordered Captain Charles H. Russell, 1st Maryland Cavalry, to pass through the Confederate noose and “try to reach somebody that had ever heard of the United States Army, or any general of the United States Army, or anybody that knew anything about the United States Army, and report the condition of Harpers Ferry.” Miles believed he could hold out for at least 48 hours – an occurrence not anticipated by Lee or Jackson in the execution of Special Orders 191.

Jackson faced a serious dilemma on the night of September 13 – 14. Although pleased with the success of McLaws on Maryland Heights and Walker on Loudoun Heights, Miles still held an advantage: Bolivar Heights.

From his position on School House Ridge, 1,500 yards west of Bolivar Heights, Stonewall studied his opponent. The disadvantages for the Confederates became apparent. Bolivar Heights towered 200 feet above School House Ridge, providing the Federals with the high ground opposite Jackson. Miles had positioned the bulk of his 14,000 men on Bolivar Heights, yielding

numbers nearly equal to Jackson’s force on School House Ridge. Miles had deployed most of his cannon on Bolivar Heights, where they could sweep more than three quarters of a mile of open ground toward School House Ridge. The Potomac and Shenandoah rivers formed the right and left flanks of Bolivar Heights, making it difficult to turn the position. Even if the Confederates utilized the river approaches, the steep, vertical bluffs of Bolivar Heights made access problematic. Finally, Miles had an interior line that permitted rapid communication and potential shifting of troops to pressure points.

“The position before me is a strong one,” Jackson admitted in a message to McLaws and Walker. In fact, Jackson never faced a stronger natural bulwark held by the enemy.

Yet Jackson could not despair. He must eliminate the Federal thorn. He must bring Lee victory.

An artillery bombardment developed as Jackson’s first solution. Stonewall reasoned he could make Bolivar Heights untenable with Confederate cannon crowning the crests of Maryland and Loudoun Heights. From these superior elevations, plunging fire could disrupt and possibly destroy Union battery positions. In addition, gravity would prevent Federal shells from reaching the mountain tops. Thus, Jackson’s guns could blast the enemy unimpeded.

One problem existed with this plan – carrying the cannon to the crests. Maryland Heights stretched 1,200 vertical feet above the Potomac valley. Loudoun Heights soared 900 feet above the Shenandoah shoreline. Hauling one-ton guns up these rugged, inhospitable slopes would be difficult at best. Time – considerable time – would be required. And although Jackson didn’t know it, he was running very short on time.

Unbeknownst to Stonewall, near noon on the 13th, about the time Jackson was aligning forces on School House Ridge, Major General George McClellan was examining a communiqué found on the outskirts of Frederick. It was Special Orders 191 – a lost copy! “I think Lee has made a gross mistake,” the jubilant Union commander declared in a telegram to President Lincoln. “I have all the plans of the rebels and will catch them in their own trap … Will send you trophies.”

As McClellan plotted to strike Lee’s divided and scattered army – including a rescue mission to Harpers Ferry – Jackson prodded his subordinates to hustle artillery to the crests of Maryland and Loudoun Heights.

“[E]stablish batteries wherever you can to take advantage, for the purpose of firing upon the enemy’s camps, and at such other points as you may be able to damage him,” Jackson instructed at 7:20 a.m. on Sunday the 14th. “I desire to remain quiet, and let you . . . draw attention from [Bolivar Heights], so that I may have an opportunity of getting possession of the hill without much loss.”

Then Jackson showed some Sabbath compassion. “So soon as you get your batteries all planted, let me know, as I desire . . . to send in a flag of truce, for the purpose of getting out the non-combatants, should the commanding officer refuse to surrender.” But “Cromwell” retired compassion in an instant. “Should we have to attack,” Jackson declared, “let the work be done thoroughly; fire on the houses when necessary. The citizens can keep out of harm’s way from your artillery. Demolish the place if it is occupied by the enemy, and does not surrender.”

Sunday the 14th was no day of rest for hundreds of Confederates dragging cannon to the mountain crests. Fortunately, abandoned roads formerly used for hauling charcoal on both Maryland and Loudoun Heights speeded the labor. By 10 a.m., Walker had five rifled pieces positioned on the peak of Loudoun Heights. Jackson welcomed the good news, but he ordered Walker to wait. “I do not desire any of the batteries to open until all are ready on both sides of the river,” Jackson signaled. “I will let you know when to open all the batteries.”

Then came word of trouble. Walker learned, in a signal message from McLaws, that the Union army was threatening McLaws’s rear. Walker relayed the concern to Jackson. Now aware of the unexpected Union thrust – and likely baffled by it – Jackson stubbornly clung to his coordinated ring of fire. “Do not open until General McLaws notifies me what he can probably effect,” he cautioned Walker. Old Jack, the former instructor of artillery at VMI, desired a textbook operation.

But Walker grew impatient. Concerned about his own division’s vulnerability, Walker ordered his five cannon to commence firing shortly after 1 p.m. Within minutes, Jackson’s batteries on School House Ridge were yanking lanyards; and by 2 p.m., four rifled pieces atop Maryland Heights were hurling shells from the north.

“The cannonade is now terrific,” wrote Lieutenant Henry Binney, Miles’s aide-de-camp. “The enemy’s shell and shot fall in every direction; houses are demolished and detonation among the hills terrible.”

For more than five hours, over fifty Confederate cannon launched missiles at the hapless Harpers Ferry Yankees. The eight-gun Federal battery nearest Loudoun Heights was silenced, and thousands of bluecoats hunkered in narrow ravines to escape the rain of iron. Yet at dusk, the stars and stripes continued to fly, frustrating Jackson further.

Stonewall gripped reality – artillery alone would not reduce the enemy. He must attack.

Thence Jackson displayed his tactical brilliance – perhaps his best tactical plan of the war. His plan called for three maneuvers: First, a flanking march and attack against the enemy’s left on Bolivar Heights; second, a feigned assault against the Union right center on Bolivar Heights as a diversion; and third, a flanking march and redeployment of ten cannon to the base of Loudoun Heights.

The rugged mountainous terrain of Harpers Ferry made each of these maneuvers difficult, perhaps even impossible. The black night of September 14 – 15 further complicated Jackson’s plans. But part of Jackson’s genius was the improbable midnight marching to places where neither soldier nor cannon dare go.

As the darkness of the 14th settled over the Shenandoah Valley, A. P. Hill’s division left its position on School House Ridge and skirted the Shenandoah, silently scaling vertical bluffs and slipping into positions behind the Union left on the Chambers’ farm. Coinciding with Hill’s flanking effort, the Stonewall Brigade launched a night demonstration from School House Ridge toward the Federal right and center, duping Miles to pull troops away from his left (Hill’s target). And perhaps most remarkable – the night flanking maneuver by artillery – transferred ten guns from School House Ridge, with horses and cannon first splashing across the Shenandoah, then scaling Loudoun Heights to a shelf overlooking the Bolivar Heights ravines.

Stonewall’s remarkable tactics dramatically changed the situation for Dixon Miles. During eleven hours of darkness, Jackson had decoyed his enemy; deployed 5,000 infantrymen and 20 cannon on his left flank; and positioned artillery at point-blank range to fire into the ravines. Jackson had out-generaled his opponent.

Shortly after dawn on the 15th, the Confederates opened a blistering barrage from their new positions. “The infernal screech owls came hissing and singing, then bursting,” recalled a New York soldier, “plowing great holes in the earth, filling our eyes with dust, and tearing many giant trees to atoms.”

By 8 a.m., Miles had had enough. Outmaneuvered, outgunned, and outnumbered, Miles and a Federal council of war unanimously decided upon surrender.

“Through God’s blessing,” Jackson scribbled in a note to General Lee, “Harpers Ferry and its garrison are to be surrendered.” When the commanding general received the message about noon on the 15th near the Antietam Creek, he made his decision to stand in Maryland and to reunite the army near Sharpsburg.

Jackson’s dramatic victory at Harpers Ferry reaped 73 captured cannon; 200 wagons; about 13,000 small arms; and nearly 12,700 Union prisoners. And what price did Jackson pay? Two hundred and eighty nine casualties. No Confederate general – and no Confederate victory anywhere – matched these results.

It’s time to give Stonewall’s triumph at Harpers Ferry the credit it deserves.