Slavery in the Colonies: The British Position on Slavery in the Era of Revolution

When we discuss the existence, practice, and tolerance of chattel slavery in North America during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, we must first recall the era by which we are reading for discussion. We must be cautious in our conclusions without reading the historical record accurately and we must understand that the denouncement of slavery’s existence did not occur in a straight line, but one whose evolution ebbed and flowed with the begrudging of time and experience. The existence of slavery in human history was not unique to North America. In virtually every civilization you will find some form of enslavement of fellow human beings by the ruling parties. What must be remembered here is that the principles of the Enlightenment and that of English common law were what sparked the incentive for a change in the way human beings treated their fellow men and women.

We know that the first enslaved Africans arrived in Virginia in 1619 and that the practice of slavery would continue uninterrupted for the next two hundred and forty-six years in North America. What we must remember though is that British interests dictated many things, and slavery was only one component. England’s economic expansion in the sixteenth century owed largely to her navy, whose vast outreach across the world’s oceans allowed the British government to create new modes of commerce and wealth. Trade became the lynchpin of the English model. From as far east as India to the tropical islands scattered about the Caribbean, the British economy became dependent on rich and exotic commodities such as tobacco, sugar cane, and indigo. To turn a profit, the British established plantations within these islands and along the east coast of North America whose fertile soils could produce the necessary exports. The British concentrated their efforts within the Atlantic slave trade by sending cargo ships full of captive Africans to the Caribbean. There, they were held in bondage and worked mostly the sugar cane plantations. In America, the importation of captives was less prevalent, at least in the first decades. The main force behind the plantations of sixteenth-century British America were indentured servants. These people, most of whom were white, were often criminals, runaways, or undesirables from England who either volunteered or were forced into service for a set amount of time. Once their time had been worked, they often were eligible for freedom. African slaves could be indentured servants too, persons who were brought over and could work under a contract. Others who were enslaved were emancipated after a set number of years worked. In these early years, most colonial laws were flexible when it came to the structure of chattel slavery. Even former slaves who were now free could own enslaved Africans of their own.

Changes began occurring after several events. Bacon’s Rebellion in Virginia in 1676 shook local communities at the risks of having large portions of the populous in a resentful state because of their work conditions. By 1705, English policy began to shift away from indentured servitude as a form of practical employment for plantation owners and farmers. To curb the shortages in laborers, the British government and their colonial counterparts began to accelerate the importation of enslaved Africans. A handful of insurrections, including the New York riots and the Stono Rebellion, further terrified slave owners that their laborers would rise up and overtake their communities. As a result, colonies, mainly Virginia and the Carolinas, set about establishing the economic structure that would establish slavery as not only an economic benefit but also one of property. And under English common law, property was a sacred right that governments had limited authority in repressing. By the 1740s, chattel slavery existed in every North America colony and the practice of breeding slaves – it was cheaper to claim the children of current enslaved people as property than to purchase new arrivals – became an economic incentive unto itself. Despite this turn of events in just a few decades, there remained visible free African American communities on the outskirts of colonial society.

Because our focus is on the British position of slavery, we must keep in mind how London ruled over her colonies during much of the first half of the eighteenth-century. The government of King George II was quite ambivalent when it came to North America. Policies of low taxes and free trade essentially dominated the colonies. As a result, this helped prosperous towns grow and regional cultures to establish themselves. In the eyes of the British government, slavery was a benign feature of its economy so long as it produced results. In America, what rumblings of abolition existed were very few and far between. Among the earliest to speak out against slavery’s existence was John Woolman, a Quaker from Burlington County, New Jersey. Drawing from religious texts and the Enlightenment, which demanded thinkers use reason, Woolman challenged how an Englishmen could tolerate such cruelty and injustice to their fellow human beings?

Indeed, as the effects of the Enlightenment grew, coupled with calls for religious diversity and a growing consensus of a natural rights phenomenon, the existence of slavery on both sides of the Atlantic came under scrutiny. Moral opinions were shifting at the same time as hostilities between the colonies and London emerged. The 1772 court case of Somerset v. Stewart in London found that chattel slavery was not compatible with English common law, effectively dismissing its legitimacy on the British mainland. As a result, abolitionists on both sides of the Atlantic used its decision to champion emancipation for those held in bondage. Indeed, as the years that saw the outset of the American Revolution approached, the term "slavery was widely used by American Patriots as a battle cry to remove themselves from the yoke of British authority. To remain under such authority, where no American held the right to representation in self-government, was a ‘form of slavery’ to many. The irony in using this sort of language was not lost on many British Tories, who called out these rebel hypocrites. “We are told, that the subjection of Americans may tend to the diminution of our own liberties; an event, which none but very perspicacious politicians are able to foresee. If slavery be thus fatally contagious, how is it that we hear the loudest yelps for liberty among the drivers of negroes?” wrote Dr. Samuel Johnson in 1775. Indeed, these sentiments not only labeled many of the American leaders as hypocrites, but it also took a swipe at the very notion that America was founded on principles that were universal for all humans, and as Thomas Paine famously said, “we could start the world anew.”

After war officially broke out in Massachusetts in the spring of 1775, each side positioned itself in ways that would both benefit some black Americans while also deliberately ignoring others. In the case of the Continental army, black citizens were barred from enlisting. However, exceptions were made for the portions of sailors and artisans affiliated with the Marble Headers under command of John Glover. Despite attempts to persuade Gen. Washington and members of Congress to allow the enlistment of both free and enslaved blacks, the American army would not risk the fragile unity that existed among the ranks of both the army and the legislative bodies. This would be tested by British orders to do the exact opposite. Sensing a vulnerability, British officials led the way for inciting mistrust of an integrated American war effort. Though there is clear evidence that the British themselves were wary of arming slaves, they nonetheless were determined to destroy the rebellion and utilize a manpower pool on the far side of the Atlantic. In 1775, Lord Dunmore, Royal Governor of Virginia, issued his Proclamation that promised freedom to any enslaved person who joined the British army. A company of former slaves was raised and named the Ethiopian Regiment. However, smallpox wiped most of them out before they could see a major battle. Sir Henry Clinton issued the Philipsburg Proclamation in 1779 that escaped slaves would receive full sanctuary behind British lines. We cannot be certain how many former slaves abandoned their plantations and came through the British lines. By the end of the Revolution, it’s estimated that nearly one hundred thousand slaves escaped to British authorities, constituting a loss of about ¼ of the number of enslaved peoples in the United States at the time.

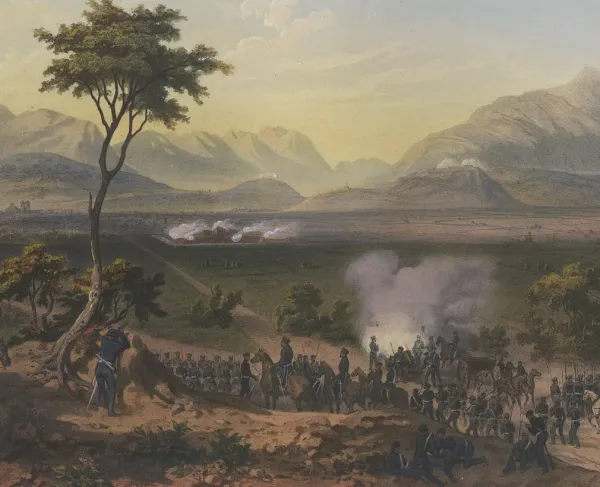

We must caution though that these calls by the British were not done because they were abolitionists on a moral crusade. The British were attempting to disrupt the continental unity at any cost. Creating a slave insurrection in the southern states might have drawn the colonists back into a regional mindset, and perhaps look to Parliament to end the unrest. It also must be noted that in many ways the British took advantage of the American slave system for their own benefit. By promising freedom, the British would potentially benefit in the short term by gaining thousands of laborers, carpenters, cooks, and scouts who could assist the army. Notice that none of these positions involved fighting. Most of those who came into the British encampments were given jobs that sustained the army, like the Black Company of Pioneers. Very few black Americans were given muskets to march off into battle. However, it is notable that in a few instances this was indeed the case. When the British landed at Charleston, South Carolina in 1780, it sent mixed units containing African Americans into the city. The sight of former slaves now armed and fighting with the enemy terrified southern residents. It was a short-term victory for the former slaves, but its memory would loom large over the southern states and have dire consequences in the following generations.

While the British army unofficially employed a majority of former slaves now in their midst, other African Americans took up arms against Continental and Patriot forces to spark unrest. New Jersey saw the rise of Colonel Tye, a former slave, and leader of the Black Brigade, who commanded an impressive assault on the state’s countryside, particularly his former home of Monmouth County. Other instances of black troops fighting for the Crown eventually changed the minds of Washington and Congress – who issued orders to form the First Rhode Island Regiment in 1778. By 1781, upwards of one-fifth of the Continental soldiers present at the Siege of Yorktown were African American.

Other factors to consider are the estimated several thousands of slaves who could have escaped but chose to stay instead. Many plantations saw their abandonment by their white owners at approaching enemy soldiers. Others walked away after becoming insolvent on their properties from a shortage of laborers. In some cases, the slaves that remained essentially took over the land for themselves. Because lost land claims by loyalist citizens were never settled after the war, it is hard to determine how many former slaves “inherited” the land of their former masters. At any rate, the British plan of disrupting the southern economy by “handing freedom” to enslaved people had a resounding effect.

Coupled with the principles championed and won by the American Revolution, the 1780s saw an uptick in abolition movements and the emancipation of slaves. Many plantation owners, whether out of economical practicalities or instilled with the new republican ideals of the time, freed their slaves. What seemed to be an evolving belief in the rights of humans only went so far. Despite some legitimate successes and the development of many educational programs for African Americans, the emerging generation slowly rolled back the gains that had been made. New laws placed restrictions on free African Americans. In many southern states, the fear of armed slave insurrections continued to haunt communities. Laws soon demanded that those who were free must leave or risk being enslaved once more.

For her part, Great Britain banned slavery in all her territories in 1807. Its leaders remained vocal of their place on the right side of history, even though they continued to profit and benefit from the southern American slave economy for decades. Indeed, during the Civil War, British officials were secretly plotting to scuttle any chance of American reconciliation and actively sought to help legitimize the Confederacy, much like France had done for the United States in 1777. It would take several actions by President Lincoln to disrupt this plot, much to the dismay of both Confederate leaders and the British government.

Further Reading

- Major Problems in the Era of the American Revolution, 1760-1791 By: Richard D. Brown

- Slave Nation: How Slavery United the Colonies & Sparked the American Revolution By: Alfred W. & Ruth G. Blumrosen

- Black Patriots and Loyalists: Fighting for Emancipation in the War for Independence By: Alan Gilbert

- The Transformation of Virginia, 1740-1790 By: Rhys Isaac

- Major Problems in American Colonial History By: Karen Ordahl Kupperman

- The Negro in the American Revolution By: Benjamin Quarles