To Secure Western Virginia for the Union: The First Campaign

Hoping to slow a rumored invasion of the Commonwealth, on the night of May 25, 1861, Confederate troops under the command of Colonel William J. Willey burned two bridges on the main line of the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad west of Grafton, Virginia (toady West Virginia). Emblematic of a war that would divide families, communities, and a nation, the colonel’s half-brother, Waitman T. Willey, would soon lead the statehood movement to dissever the western counties from Virginia and form a new state. Rather than prevent an invasion, William’s bridge burnings would instead precipitate the first campaign of the Civil War, which would in turn ensure the safety of those delegates – his half-brother among them – meeting to formulate a new state.

Following Virginia’s secession ordinance, Gen. Robert E. Lee assumed command of all Virginia state forces. With the Confederate capital on the move to Richmond, Lee began recruiting in earnest to shore up potential avenues of invasion from Federal troops, including Norfolk to the east, Washington D.C. and the Shenandoah Valley to the north, and Ohio and Pennsylvania to the northwest. On May 4, 1861, Lee dispatched Col. George Porterfield to Grafton in the northwest corner of the state to establish a recruiting camp and keep an eye on the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad. Instead, when Porterfield arrived in Grafton, the only troops he found was a company of Federal soldiers.

The month prior, 32 of the 55 votes against Virginia’s secession ordinance came from the northwestern counties. The delegates from these counties called a convention in the northern panhandle city of Wheeling to repudiate secession and debate the appropriateness of separating from Virginia. On April 20, Wheeling mayor Andrew Sweeny rejected Virginia Governor John Letcher’s call for Sweeny to seize the custom house, post office, public buildings, and documents in the name of Virginia. Sweeny responded to Letcher that “I have taken possession of the custom house, post office, and all public buildings and documents in the name of Abraham Lincoln, President of the United States, whose property they are.” While Robert E. Lee refused to believe that “any citizen of the state will betray its interests,” the northwestern counties appeared more on the verge of rebellion from Virginia than rebellion from the Union.

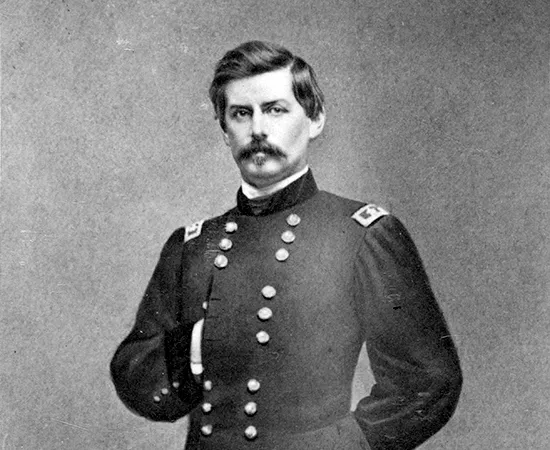

Meanwhile, Union troops were organizing on both sides of the Ohio River. In April, Gen. George B. McClellan had been named Major General of Ohio Volunteers, tasked with organizing Ohio’s raw recruits and guarding the borders of the state against invasion. On May 3, McClellan was placed in command of the Department of the Ohio, which included the states of Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, and later western Pennsylvania, western Virginia, and Missouri. Ohio Governor William Dennison urged McClellan to “defend Ohio beyond, rather than on her border.”

Beyond Ohio’s border, a regiment of loyal Virginia troops organized at Wheeling. The First Virginia Infantry (US) was comprised of men from Virginia, Ohio, and Pennsylvania, but was void of any accoutrements, uniforms, even without enough arms for all of the enlisted men. Additional Union troops arrived in Wheeling in late May, forming the Second Virginia Infantry (US). While lacking in supplies and the materiel of war, these regiments would soon lead the vanguard of McClellan’s advance into Virginia.

On May 22, 1861, Thornsbury Bailey Brown was killed at Grafton, the first enlisted Union soldier to be killed by a Confederate soldier. Two days later Confederates under Porterfield occupied Grafton. The burning of the Baltimore & Ohio bridges on May 25 was the act of war George McClellan had been waiting for. He could now send troops across the Ohio River to secure the railroad and public property without appearing the aggressor.

McClellan ordered Colonel Kelley to secure the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad and repair the burned bridges before moving on the Confederates at Grafton. Kelley would be supported by two Ohio regiments crossing the Ohio River at Bellaire, as well as two Ohio regiments and two guns of the First Ohio Light Artillery crossing at Parkersburg. McClellan sought to reassure Virginians that his troops were crossing the Ohio River “as your friends and brothers, as enemies only to the armed rebels who are preying upon you,” and urged his men to “remember that your only foes are the armed traitors,” and to respect all private property.

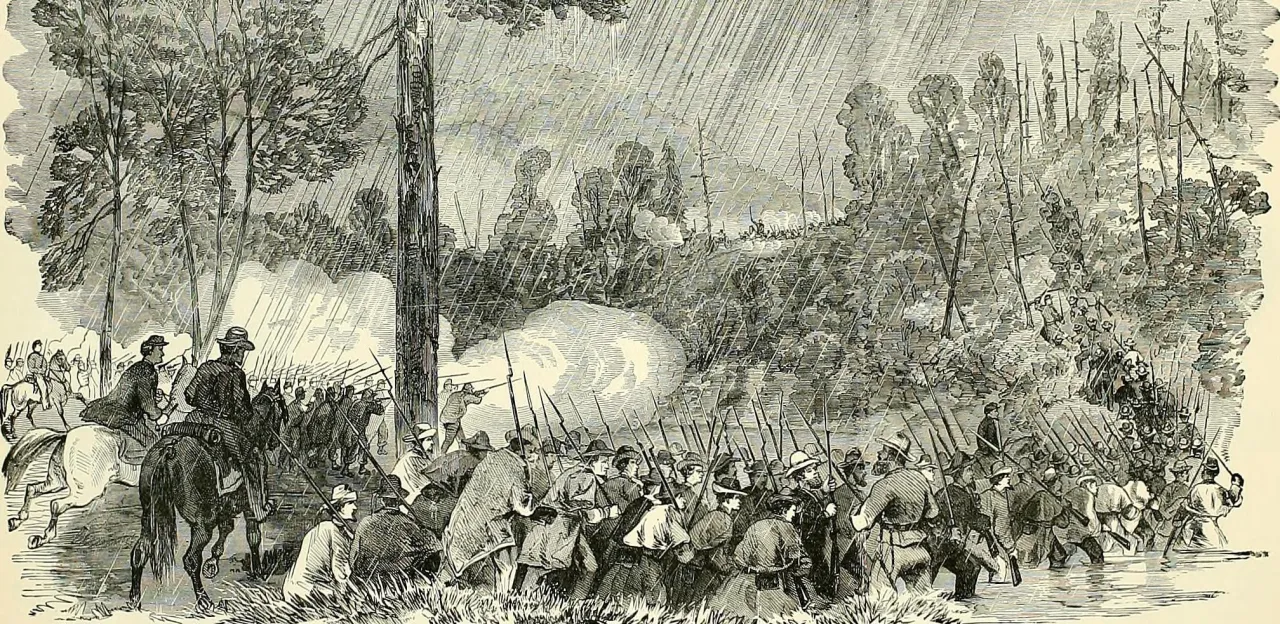

In the face of McClellan’s advance, Porterfield abandoned Grafton, pulling his troops back to Philippi, while Kelley occupied Grafton on May 30. As the small Confederate army of 775 men attempted to reorganize at Philippi, Kelley led a two-prong advance on the town. During the early morning hours of June 2, in a driving rain Kelley’s columns converged on Philippi as the First Ohio Light Artillery lobbed shots into the town from a nearby hilltop. In a widely publicized engagement lasting only a few minutes, the Confederates were routed from Philippi, retreating nearly 40 miles south to Huttonsville. Colonel Kelley was grievously wounded in the closing moments of a nearly bloodless fight. In a matter of days, the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad and the safety of the Wheeling Convention had been secured.

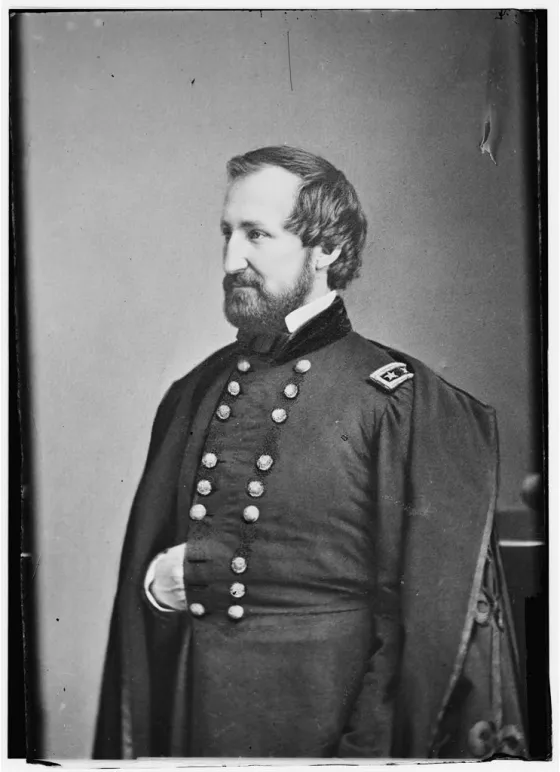

The setback at Philippi called for a shakeup in Confederate command, and Porterfield was soon replaced by Gen. Robert S. Garnett, who bemoaned the assignment as “being sent to my death.” Garnett worked to establish a line of defense aimed to blunt the Federal advance, positioning troops at Rich Mountain on the Staunton-Parkersburg Turnpike, and sixteen miles north at Laurel Hill, near Belington. While reinforcements swelled Garnett’s ranks to 4,500 men, McClellan would soon bring 20,000 men to bear in western Virginia. Garnett knew he must be judicious with his small army, vowing to fight only when “I can see a reasonable hope for success.”

McClellan had overseen the early stages of the campaign from his headquarters in Cincinnati, but news of Confederate reinforcements required direct oversight. Arriving at Grafton on June 23, he proclaimed to his soldiers that “I have heard that there was danger here. I have come to place myself at your head and to share it with you.” He quickly organized his troops for an advance on the Confederates at Rich Mountain and Laurel Hill.

On June 30, two brigades of Federal troops occupied Buckhannon, less than two dozen miles from the Confederate works at Rich Mountain. The following week, another brigade of around four thousand troops under the command of Brigadier General Thomas H. Morris, moved on the Confederates entrenched at Laurel Hill. In what would later become a hallmark of his command of the Army of the Potomac, McClellan feared that the Confederates vastly outnumbered his command, anticipating as many as two thousand troops facing him at Rich Mountain and up to eight thousand confronting Morris at Laurel Hill. In reality, only around 1,300 Confederates held the Rich Mountain works, while Garnett held Laurel Hill with around 3,500 men.

As McClellan waffled at Buckhannon, a subordinate general ordered an unauthorized July 5 expedition to Middle Fork Bridge, midway between the Buckhannon and Rich Mountain, alerting the Confederates to a possible advance on their works. An enraged McClellan, fearing he had lost any element of surprise, put his columns on the road, and within four days had three brigades of troops arrayed in front of the Confederate works at the base of Rich Mountain.

Meanwhile, over four days of sustained skirmishing, Federal troops clashed with the Confederates at Laurel Hill, convincing Garnett that the main Federal thrust would come in that direction. Instead, sixteen miles to the south McClellan readied for an assault on the Confederate works at Rich Mountain. Rather than a frontal assault, McClellan directed Gen. William S. Rosecrans to take his brigade on a sweeping flank attack to the top of Rich Mountain, placing him behind the Confederate works. Once engaged there, McClellan would direct the frontal assault.

On July 11, in a light rain, Rosecrans flanking march slogged up the mountain, a worried McClellan waiting below for sounds of battle. Rosecrans found approximately 300 Confederates at the summit, who for more than two hours held their ground in the face of Rosecrans assaults before falling back to Beverly. Fearing Rosecrans had met a setback, McClellan’s attack on the Confederate works at Camp Garnett, two miles below the summit, never materialized. Realizing their untenable situation, some 600 Confederates, with Federal troops now in their front and rear, executed a daring nighttime escape from Camp Garnett, though many were captured within days. The road to Beverly – and the rear of Garnett’s army sixteen miles north – was open.

Garnett’s position at Laurel Hill was now untenable. Leading his men cross-country over rough mountain roads, it was hours before Union forces realized Garnett was gone. Giving chase, the Federal troops caught up with Garnett near Corrick’s Ford (modern day Parsons) on the Cheat River. Here the Confederates dug in their heels, determined to protect two river crossings, and buy their army time to escape. It was here that Garnett’s prediction of being sent to his death proved prophetically true, as he was killed while directing his troops, the first general officer on either side to be killed during the Civil War. It would take more than a week of wandering through the wilderness for the remnants of Garnett’s army to reach the safety of Confederate lines at Monterey.

While events unfolded in northwestern Virginia, further south in the Kanawha Valley, Federal forces under Gen. Jacob Cox clashed with Confederate under former Virginia governor Henry Wise at Scary Creek, west of Charleston. Fought to a standstill, the Confederates soon withdrew up the Kanawha Valley towards Fayetteville, leaving the Kanawha Valley to the Federal troops.

McClellan occupied Beverly and telegraphed Washington news of complete victories at Rich Mountain, Laurel Hill, and Corrick’s Ford – the first major Federal victories of the war. Headlines splashed across northern newspapers only days before the first major Federal defeat of the war at First Bull Run. It would take only one day following that bloodletting for George McClellan to be recalled from western Virginia. “Circumstances make your presence here necessary,” charged General Winfield Scott. Leaving his army under the command of William S. Rosecrans, McClellan proceeded to Washington.

The Federal victories in western Virginia during the summer of 1861 helped to secure the western end of the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad and established a foothold in the Commonwealth of Virginia that would last throughout the war. The campaign and its widely heralded, if not minor victories, made a hero of George McClellan when the North needed one in the worst way. Perhaps most importantly, McClellan’s victories in western Virginia helped to protect the fledgling government forming in Wheeling, a government loyal to Abraham Lincoln and the Union. Within two years, that government formed the state of West Virginia, the 35th state admitted to the Union, and the only successful secession in United States history.

Further Reading:

- Yanks from the South! The First Land Campaign of the Civil War, Rich Mountain, West Virginia By: Fritz Hasselberger.

- Rebels at the Gate: Lee and McClellan on the Front Line of a Nation Divided By: Hunter W. Lesser.