It is hard to fathom that an uninhabited, wild, barrier island like Morris Island exists so close to the bustling port city of Charleston, S.C. But if you can find a way to get to that isolated stretch of wilderness, you’ll find a long, wide expanse of sandy beach with an atmosphere imbued with a deep sense of history.

Morris Island mostly likely would be developed today were it not for the efforts to preserve it by a coalition of organizations that included the American Battlefield Trust, then called the Civil War Preservation Trust. Remarkably, the island’s ultimate preservation in 2006 was even supported by the developer himself.

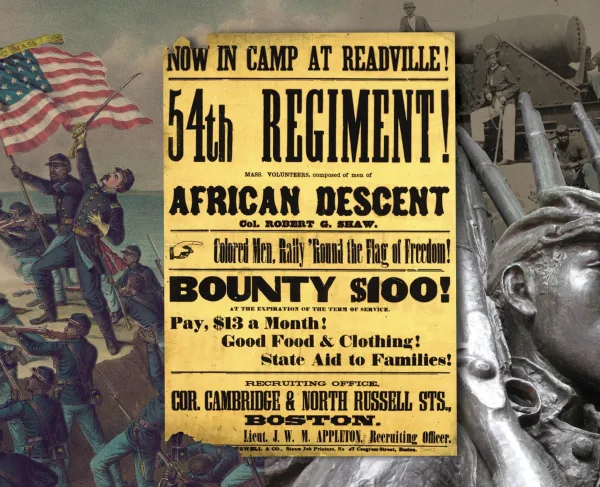

Located at the southern entrance of Charleston Harbor, Morris Island was the scene of the famous assault of the 54th Massachusetts against Fort Wagner, immortalized in the Academy Award-winning 1989 movie Glory. The island also held some of the massive Union guns that shelled Charleston for 545 days during the war. The evidence of at least one emplacement remains visible today. Although a few summer homes appeared and disappeared decades ago, the 840-acre island has long been uninhabited and accessible only by boat. Generations of Charlestonians grew up exploring and camping there.

The historic northern end was still privately owned when Greenville, S.C. developer Harry Huffman optioned some 126 acres in 2003 to build houses. The preservation fight was led by Blake Hallman, an instructor at the Culinary Institute of Charleston and a native who had often camped on the island.

Hallman, a board member of the South Carolina Battleground Preservation Trust (SCBT), teamed up with Jim Campi of the Trust to create the Morris Island Coalition, a diverse group that also included the City of Charleston, the Coastal Conservation League, the NAACP, Sons of Confederate Veterans, The Trust for Public Land (TPL), the National Trust for Historic Preservation (NTHP) and even the Charleston Chapter of the Surfrider Foundation.

As the coalition began fighting to save the land, Huffman had filed for zoning variances to allow new homes. He asked for zoning for 120 homes. “The county told him no,” Hallman recalled. “Then he asked for it to be zoned for 60 homes. And they told him no. So, then he asked for it to be zoned for 20 homes. And they said, ‘That seems like a more reasonable number.’”

The coalition redoubled its efforts when the Trust named Morris Island one of the most endangered battlefields in the nation in 2004. Huffman became frustrated with the entanglements and made national headlines in January 2005 when he offered Morris Island for sale on the online auction site eBay for $12.5 million. “It’s sad to see such a priceless piece of American history put up for auction like some unwanted holiday gift,” Trust spokesman Jim Campi told the Associated Press.

A Trust-commissioned poll revealed that 71 percent of local registered voters polled supported preserving the island and 77 percent opposed the proposed rezoning. Huffman did not renew his option. Later in 2005, Edward R. “Bobby” Ginn III, a Florida resort developer, took an option to buy the island acreage.

Hallman considered Ginn a greater threat than Huffman because Ginn had more money. The coalition and Trust went on the offensive with the slightest hint of trouble. When Ginn took the routine step of recording the two plat maps noting his purchase, Campi put out a news release that read in part, “Just in time for the holidays, the Grinch has reared his ugly head outside Charleston Harbor.”

Ginn was urged to preserve the land by longtime Charleston Mayor Joe Riley, a preservation supporter. Riley’s former executive assistant, David Agnew, had become South Carolina advisory chairman for the TPL. Riley urged Ginn to talk with Agnew, who believed he could “strike a chord” if he could just tell Ginn about TPL and its mission. They met in Agnew’s King Street office and soon struck a deal.

On February 2, 2006, Ginn closed on the purchase of the Morris Island land for $6.8 million and immediately sold it to the TPL for $4.5 million – an instant $2.3 million loss. TPL then flipped the property to the City of Charleston to preserve in perpetuity. Having survived seven development efforts in its modern history, Morris Island was now saved forever. Of all the developers intent on developing hallowed ground, Ginn set a standard as the most generous and amenable to historic preservation.

“I consider it to be a real win-win for everybody,” Hallman said. Ginn “did the right thing. He collected all the accolades due to him. The island was preserved, which is what the citizens wanted. And then the overwhelming majority said, ‘Don’t touch a thing. Leave it exactly as it is.’ And so, we took that to heart, and that's the end result.”

Hallman said the Trust's involvement in mobilizing the community was crucial. At a Trust board meeting in Charleston in January, 2006, Hallman recalled, “I told their board of trustees that I truly felt that the Morris Island Coalition would not have succeeded in helping to preserve the island had it not been for the role played by the Civil War Preservation Trust. Its star glows brightest of all.”

Related Battles

1,515

174