Confederate artillery in front of the Dunker Church

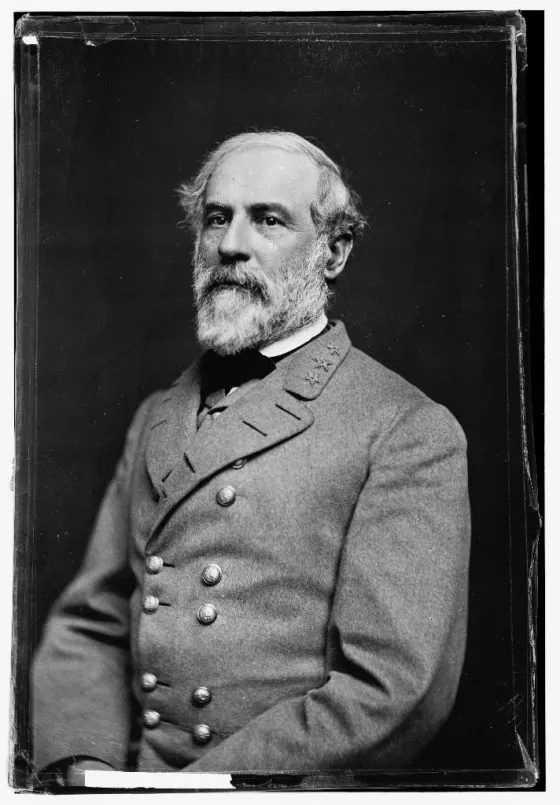

General Robert E. Lee’s Confederate Army of Northern Virginia entered the final stage of a protracted season of campaigning as it marched toward Maryland during the first week of September 1862. General Joseph E. Johnston’s disabling wound at the battle of Fair Oaks had brought Lee to command of the army on June 1, 1862, and within a month he had seized the initiative from Major General George B. McClellan, driving the Union’s Army of the Potomac away from Richmond in the Seven Days' Battles. With his capital safe, Lee marched northward in late August and won a stunning victory over Major General John Pope’s Army of Virginia at the Second Battle of Manassas or Bull Run. These two Confederate victories had cleared Virginia of any major Union military presence, and Lee sought to build on his success by taking the war across the Potomac River into the United States. Lee’s bold maneuvering ended when he retreated from Maryland following the Battle of Antietam on September 17, 1862, closing a three-month period that should be viewed as a single huge operation that reoriented the war from the outskirts of Richmond to the Potomac frontier and marked Lee’s spectacular debut as a field commander.

In taking his army across the Potomac River in early September, Lee had in mind strategic, logistical, and political factors. He believed that the soldiers of McClellan and Pope “lay weakened and demoralized” in the vicinity of Washington, D.C., and he sought to maintain aggressive momentum rather than assume a defensive position and allow the Federals to muster their superior strength to mount another offensive. If he remained in Virginia, Lee would be forced to react to Union movements, whereas in Maryland or Pennsylvania he would hold the initiative. Lee believed he could easily flank the enemy by crossing the Potomac upriver from Washington and marching the Army of Northern Virginia through Maryland. A short thrust into Union territory would not be enough; a protracted stay would be the key to Confederate success. Lee hoped to keep his army on United States soil through much of the autumn, not with the intention of capturing and holding territory but with an eye toward accomplishing several goals before returning to Virginia as winter approached.

The most important of those goals focused on logistics. Facing critical shortages of food, Lee knew that a movement into the untouched agricultural regions of Maryland and Pennsylvania’s Cumberland Valley held significant promise. If positioned northwest of Washington, Lee could force the Federals to remain between him and their capital, thus liberating war-exhausted northern and north-central Virginia, as well as the Shenandoah Valley, from the presence of the contending armies. Southern farms that had suffered from the presence of scores of thousands of troops could recover, crops could be harvested safely, and civilians could enjoy a respite from the stress of constant uncertainty about their persons and property. Meanwhile, Lee’s army would gather vital food, fodder, and other supplies from Maryland and perhaps from southern Pennsylvania. This double-sided logistical bonus, by itself, would be sufficient to render the Maryland campaign a success.

Beyond maintaining the strategic offensive and improving his logistical situation, Lee sensed an opportunity to affect political events in the United States. He read Northern newspapers carefully and knew that bitter debates raged between Northern Republicans and Democrats about civil liberties, the conduct of the war, and emancipation. If the campaign north of the Potomac went as Lee hoped, the North’s fall elections would take place while the Army of Northern Virginia maneuvered in Maryland or Pennsylvania. The presence of the premier Rebel army on United States soil would hurt Lincoln and the Republicans, believed Lee, making it easier for Democrats to press for some type of negotiated settlement.

Lee addressed the connection between military and political events in a letter to Confederate President Jefferson Davis on September 8, 1862, remarking that “for more than a year both sections of the country have been devastated by hostilities which have brought sorrow and suffering upon thousands of homes, without advancing the objects which our enemies proposed to themselves in beginning the contest.” The time had come to propose peace on the basis of Confederate independence. “Made when it is in our power to inflict injury upon our adversary,” reasoned Lee with his army’s northward movement in mind, such a proposal “would show conclusively to the world that our sole object is the establishment of our independence, and the attainment of honorable peace.” Should the Lincoln government reject the proposal, continued Lee, Northerners would know that full responsibility for continuance of the war rested with the Republicans rather than with the Confederacy. Voters would go to the polls in November 1862 “to determine . . . whether they will support those who favor a prolongation of the war, or those who wish to bring it to a termination, which can but be productive of good to both parties without affecting the honor of either.”

Lee also held high hopes for the state of Maryland. He joined many other Confederates in thinking that only Federal bayonets kept that slave state in the Union against the wishes of its residents. Citizens of Baltimore had rioted in April 1861. Marylanders had been arrested and incarcerated without benefit of the writ of habeas corpus. Thirty-one secessionist members of the state legislature, together with the mayor of Baltimore, had been imprisoned for several weeks during the autumn of 1861. Thousands of Maryland citizens wondered if their liberties would stand in abeyance for the duration of the war. Lee believed the influence of his victorious army might embolden Maryland’s military-age men to step forward in active support of the Confederacy, after which they could once again, as he put it in a proclamation to Marylanders on September 8, “enjoy the inalienable rights of freemen, and restore independence and sovereignty to your State.”

Two important factors that stood in the balance as Lee moved into Maryland played no role in the general’s decision-making. He knew nothing about Abraham Lincoln’s intention to issue a preliminary proclamation of emancipation if Union armies won a victory – something the president would do in the wake of Antietam – and thus planned without considering how his movements might shape Lincoln’s actions relating to that momentous issue. And he did not march northward with the expectation of persuading England and France to extend formal diplomatic recognition to the Confederacy. Although leaders in London and Paris, who in September 1862 edged closer to some type of diplomatic intervention than at any other time during the war, watched closely to see whether the Army of Northern Virginia would win another triumph, Lee always insisted that the Confederacy should never count on help from Europe to achieve its independence. None of his correspondence at the time of the Maryland campaign mentioned the possibility of influencing foreign observers.

As he considered the possible outcomes of his campaign, Lee expressed no fear of aggressive Federal reaction to his march across the Potomac. Through the first week of September, reports indicated that Northern troops were concentrating in the fortifications outside Washington. If a Federal army did rouse itself to confront Lee, he would have the advantage of fighting on the tactical defensive on ground of his own choosing – perhaps defending gaps in the South Mountain Range or other favorable positions. “The only two subjects that give me any uneasiness,” Lee wrote Jefferson Davis on September 4 as his army began to cross the Potomac at White’s Ford, near Leesburg, Virginia, “are my supplies of ammunition and subsistence.” The former was not an immediate problem: “I have enough for present use,” stated Lee, “and must await results [of the campaign] before deciding to what point I will have additional supplies forwarded.” As for food and fodder, the farms of western Maryland would answer the needs of the Army of Northern Virginia. Lee had summed up his analysis of the situation in the early fall of 1862 in a letter written to Jefferson Davis the previous day: “The present seems to be the most propitious time since the commencement of the war for the Confederate Army to enter Maryland.”

Learn More: Antietam

Related Battles

12,401

10,316