Lee's and McClellan's Headquarters at Antietam

On September 17, 1862, General Robert E. Lee gazed out across the fields of Sharpsburg, anxious to see how his army was faring against the Union army. As Lee daringly entered Maryland, the odds had certainly been against him as he faced a superior force in enemy territory. Not to mention, several weeks earlier, Lee held the reins of his beloved horse Traveler when the animal bucked, throwing the general to the ground and injuring his wrists. Now bandaged, Lee could barely lift his field glasses to observe the fight swirling around him.

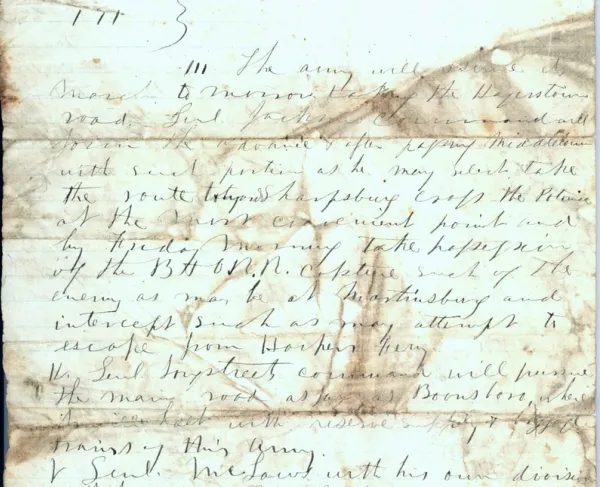

Following the battle of South Mountain, Lee and his staff arrived in Sharpsburg on September 15 along with his converging army. Riding in the back of an ambulance, the general established his headquarters in a small grove of oak trees just west of the town. Though this location is not where Lee primarily spent September 17, this was where he fulfilled administrative duties and established the central command center of the Army of Northern Virginia. By September 16, however, Lee determined himself well enough to ride but was led on horseback by an orderly instead of taking the reins himself. In this fashion, he observed the fighting and made decisions that influenced the battle of Antietam.

Meanwhile, on the afternoon of September 16, Major General George B. McClellan and his staff arrived on the field. With orders from the president to “destroy the rebel army, if possible,” they quickly found high ground near the Philip Pry house to get their first glimpses of Lee’s chosen position. However, from this vantage point, McClellan could only view portions of the Confederate line, not the Rebel army in its entirety.

As the battle began north of town and spread southward, General Lee observed much of the fighting from the general vicinity of Cemetery Hill, located centrally behind Confederate lines along the Boonsboro Pike. The elevated position not only provided the Confederate army with an effective artillery position but a place where Lee could visibly find almost every location on the battlefield. There, amid Captain Hugh Garden’s Palmetto Artillery, Lee watched the seesaw action, hastily gave orders, and anxiously awaited the arrival of Major General A.P. Hill’s division. Except when a crisis or a threat to the general’s safety occurred, Lee likely did not leave this general area.

Local legend holds that Lee even stood on a large boulder on Cemetery Hill to get a better look at the fighting. The general, perhaps braving his injury, could have very likely utilized the boulder to observe part of the fighting. The boulder was subsequently nicknamed "Lee’s Rock" and stood inside the Antietam National Cemetery. However, following the war, as the cemetery committee began to draw up plans for the gravesites, a question arose regarding the boulder’s propriety. Having become a quasi-monument to Robert E. Lee sought by visitors to the battlefield, the committee ultimately deemed it inappropriate for the boulder to be located within a Union national cemetery. Thus, the rock was destroyed and no longer sits among the graves today.

Unlike Lee, McClellan rarely ventured from his headquarters at the Pry house to observe the unfolding action, thereby denying “the inspiration of his presence at any point along the line,” as one critic wrote. On the afternoon of September 16, Little Mac rode briefly with Major General Joseph Hooker and the Union I Corps until they crossed the Antietam Creek before returning to his headquarters to spend the night. Meanwhile, McClellan’s staff prepared the Pry house for the following day’s battle. They set up “six telescopes fastened to the fence, through which he could scan as many different parts of the field” as he liked. However, unlike Lee’s observation post on Cemetery Hill, McClellan’s headquarters at the Pry House did not provide the commander a panoramic view of the battlefield. This limited scope of view perhaps informed some of McClellan’s cautious decision-making during the battle.

By late afternoon on September 17, Lee stood on this hill and anxiously watched as Major General Ambrose E. Burnside’s Union IX Corps advanced against the Confederate right flank, forcing Brigadier General David R. Jones’s division to withdraw. When he eyed a line of troops advancing in the distance, Lee, unable to raise his field glasses, turned to Lieutenant John A. Ramsay of the North Carolina Rowan Artillery and asked, “What troops are those?” Ramsay peered through his glasses and answered, “They are flying the United States flag.” The general looked again to another body of troops, this time arriving from behind Confederate lines. Lee pointed and repeated the question to Ramsay, who answered, “They are flying the Virginia and Confederate flags,” ushering the highly anticipated arrival of A.P. Hill’s division. Though Ramsay may have misconstrued the blue Palmetto flags of Brigadier General Maxcy Gregg’s South Carolinians for the Virginia banner, Lee was nevertheless assuaged with the tide of battle turned.

During the battle, Army of the Potomac chief medical officer, Jonathan Letterman, established a hospital at the Philip Pry house early on September 17 as McClellan continued to use it as his headquarters and an observation post. Quickly, wounded men trickled into the hospital while the dead and dying littered the lawn. The property served as such throughout the battle and well after, effectively ruining Philip Pry’s lucrative farm. Following the battle, McClellan appointed a committee of officers to appraise the property damages, but Pry never received compensation.

Today, Cemetery Hill hosts the Antietam National Cemetery, where 4,776 Union soldiers rest, in a twist of fate, near where General Robert E. Lee watched many of them march to their fate. A small monument marks the site of Lee’s headquarters, where a grove of trees still stands just beyond the town of Sharpsburg. Today, the National Park Service owns the Pry House, and the National Museum of Civil War Medicine sponsors an exhibit there.

Further Reading:

- Islands of Mercy: Hospitals in the Maryland Campaign By: Gordon Dammann and John W. Schildt.

- To Antietam Creek: The Maryland Campaign of 1862 By: D. Scott Hartwig

- A Field Guide to Antietam By: Carol Reardon and Tom Vossler.

Related Battles

12,401

10,316