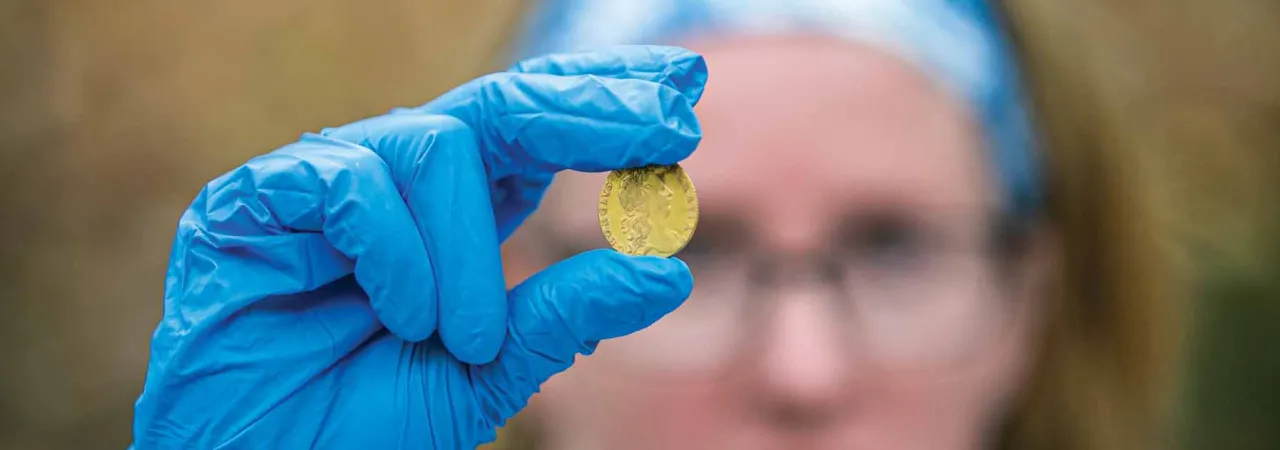

History professor Jennifer Janofsky holds a rare 1766 King George III gold guinea, the equivalent of a soldier’s wages for a month, found during the excavation.

“As long as I have served, I have not left a battlefield in such deep sorrow,” Captain Johann Ewald, an officer in the Hessian Field Jäger Corps, wrote in his diary after the Battle of Red Bank, New Jersey. On that October day in 1777, Ewald had lost five of his closest friends, including a family member, and four more of his friends were seriously wounded in their assault on American forces at Fort Mercer.

A recent archaeological discovery at Gloucester County’s Red Bank Battlefield Park has led to stunning confrontation with the violence Ewald describes. Last summer the Park recovered the remains of at least 15 individuals believed to be Hessian soldiers, or troops from German states hired by the British Empire to support its forces. The remains include skull and leg bone fragments that show these individuals may have suffered multiple wounds or dismemberment. Musket balls, canister shot, and grape shot were all found nearby. While these finds are common on the battlefield, “to see it in association with a person changes the way you understand that piece of material culture,” said Dr. Jennifer Janofsky, director of Red Bank Battlefield Park and the Megan Giordano Fellow in Public History at Rowan University.

Guided tours, trails, and special programs at the Park give visitors a thorough understanding of the battle, but Janofsky believes this moment could be an opportunity for the 44-acre historic site to interpret the brutal nature of the war – a point Revolutionary War battlefields don’t often dwell on. “I think the discovery really prompts us to reconsider the stories that we are telling and to really share that story of violence” with visitors, she said.

Just a month before the battle, General Sir William Howe had captured Philadelphia. Yet, it was only a partial victory, as American forces still held the Delaware River and countryside, which Howe needed to resupply and reinforce his troops in the city. Fort Mercer – an earthen fortification on a bluff called Red Bank along the River – became a target of Howe’s plan to seize access of this key waterway for the British Navy. On October 22, 1777, approximately 1,400 Hessians descended upon a small American force of just over 600 soldiers. The fort’s outnumbered defenders focused their cannons and small arms on the attacking force, supported by fire from several American naval vessels. The Hessian soldiers tore their way through abatis and this brutal field of fire, but never reached the fort. After approximately 40 minutes of fighting, they retreated, having suffered casualties of up to 25 percent.

The Park was aware of the potential for mass graves on the battlefield. But finding one where they did – in what would have been a trench outside the fort – was entirely unexpected. Historic maps noted soldiers’ burial locations on the opposite side of the current park. A 2014 archaeological investigation based on this documentation did not identify any potential mass burial locations. When the Park began this current excavation, Janofsky said burials “were not even remotely on our mind.”

The work began as a public archaeology project intended to investigate a quarter-acre property the County added to the Park in 2020, demonstrating the critical role of battlefield preservation in making these discoveries possible.

“It seemed like such a small acquisition when you stand on the lot,” Dr. Janokfsy said, “but we found out was that it was extremely valuable.” Hundreds of volunteers worked alongside professional teams to uncover the tract’s mysteries. One of the volunteers even discovered a 1766 King George III guinea coin while using an archaeology sifting screen for the first time. This coin – about the equivalent of a soldier’s pay for month – is an incredibly rare find that Janofsky said may have itself been the major story of the project.

But then came what Janofsky characterized as “a complete shock”: a volunteer found a human bone. This changed the course of the project, as it became not just an archaeological excavation but an investigation. The Park team worked with forensic anthropologists with the New Jersey State Park Forensic Unit to ensure that human remains were all were treated with appropriate care. Additional remains were excavated by hand within a block of soil so they could later be carefully revealed and analyzed in a lab.

Janofsky anticipates that ongoing research will reveal personal details about these soldiers that will help visitors connect with diversity of participants who fought in war. She experienced this personal connection herself when the team discovered that one of the individuals may have only been 18-22 years old, the same age as own children and her students.

“As a historian, I’ve always been drawn to the stories that haven’t been told,” she said, and she wondered what brought him to the war and who might have been mourning his loss. State forensic anthropologists hope DNA analysis will be able to identify individuals and their descendants, but that possibility continues to be, as Dr. Janofsky says, the “million-dollar question.” She is optimistic the team may be able to create a facial reconstruction of one of the recovered individuals, which would truly help her team bring these soldiers to life at the Park.

“I think most people when you say ‘the Hessians’ in the Revolution, the first word to come to mind is ‘mercenary’ and ‘mercenary’ has this very negative connotation,” said Janofsky. “The opportunity here is to share their stories and really have them be individuals in the public mind and to really talk about the complexities of who these individuals were,” she said.

Thanks to funding from the New Jersey Humanities Council, the Park will be working with several additional experts to develop new interpretation that highlights these stories. Janofsky, co-director Wade Catts of South River Heritage Consulting and their team are also working on plans to memorialize these individuals on the battlefield, and the County is exploring appropriate options for the reinternment of the remains.

Visitors will soon be able to see this site for themselves. The Park will conduct public tours to the property April through October 2023, and visitors will have the opportunity to speak people involved in the discovery. The Park is also planning to offer more public archaeology opportunities soon. If you are interested in being involved, please contact Dr. Janofsky at lawrencej@rowan.edu.

Related Battles

40

514