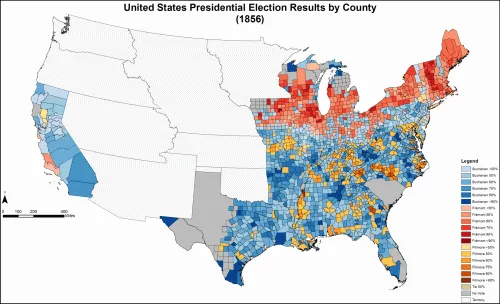

After its formation in 1854, the Republican Party successfully formed a coalition based in the Upper Midwest and Northeast Coast by absorbing most of the old Whig Party as well as some Democrats. Its main political aim: stopping the expansion of slavery into the Western territories. The party did not seek full abolition, though many of its members were morally opposed to slavery and abolitionists did make up a significant faction. Instead, the party mainly opposed slavery on the grounds that it posed a threat to the livelihood of free labor. They also believed that those most invested in preserving the institution, namely Southern white plantation owners, held a disproportionate and ultimately toxic influence over the federal government—known to many as the “Slaver Power Conspiracy.” Unfortunately for the Republicans, their first nominee for a presidential election, explorer, Mexican War veteran and former California Senator John Frémont, failed to overcome Democrat James Buchanan. Despite an extensive military and political record and a politically savvy campaigner in his wife, Jessie, Frémont’s abolitionist sympathies were far too open to win over many undecided voters. The Democratic Party also used this opportunity to smear their rival as, among other things, a Catholic, feminist, socialist, teetotaler, and even a vegetarian. Many Democrats, Southerners in particular, threatened civil war upon a Frémont victory, scaring even more voters away. Making things worse, a third-party candidate, former President Millard Filmore of the American Party split the vote between the Democratic opposition, ensuring Buchanan’s success.

As the next Republican convention began to convene in Chicago during the May of 1860, many delegates faced a difficult choice ahead of them in choosing another presidential candidate. The two obvious frontrunners going into the convention were New York Senator William Seward and Ohio Senator Salmon P. Chase. Both men were far more accomplished politicians than Frémont with significantly more executive experience as former governors of their respective states, but they also posed a major concern for the delegates. Both Seward and Chase had significant ties with the abolitionist movement, and though neither candidate explicitly called for the abolition of slavery, both men wore their personal views on the subject on their sleeves and proposed revoking the highly controversial Fugitive Slave Act of 1850, among other acts. Both men were relatively popular amongst their respective constituents, but delegates dreaded facing another election where they failed to appeal to more moderate and conservative voters in the Western states and Upper South. On the other hand, the likely alternatives posed problems of their own, like Missouri congressman Edwin Bates’ connection to the nativist Know-Nothing Party, which threatened critical support from German immigrants. The Republicans had to find someone who could at least placate all the factions in their loose coalition.

Eventually, they decided to settle on former Illinois congressman Abraham Lincoln, who for his part was neither present at the convention nor possessed any hope of nomination against Seward and Chase. That said, his recent Senate campaign against Democrat Stephen Douglas, though ultimately a failure, did earn him national attention as a moderate but firm opponent of slavery. Nevertheless, Lincoln had a number of friends in the Illinois state party, who believed that he could carry the important northern states won by Buchanan in ’56. Eventually, Norman Judd, chairman of the Republican State Central Committee in Illinois, convinced Lincoln to launch his campaign in January 1860, and as a favor to him, convinced the National Committee to pick Chicago as the site of the convention.

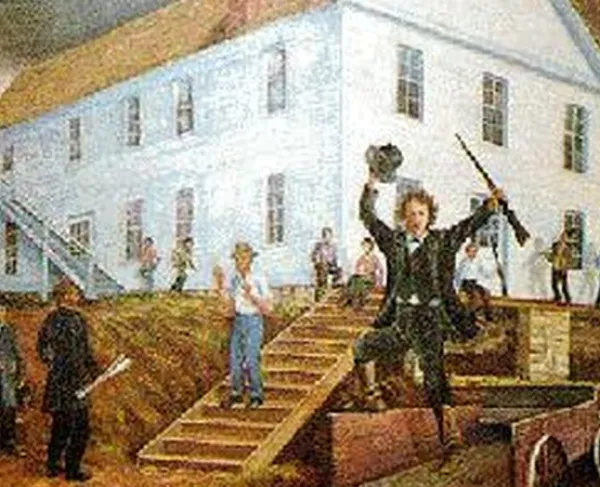

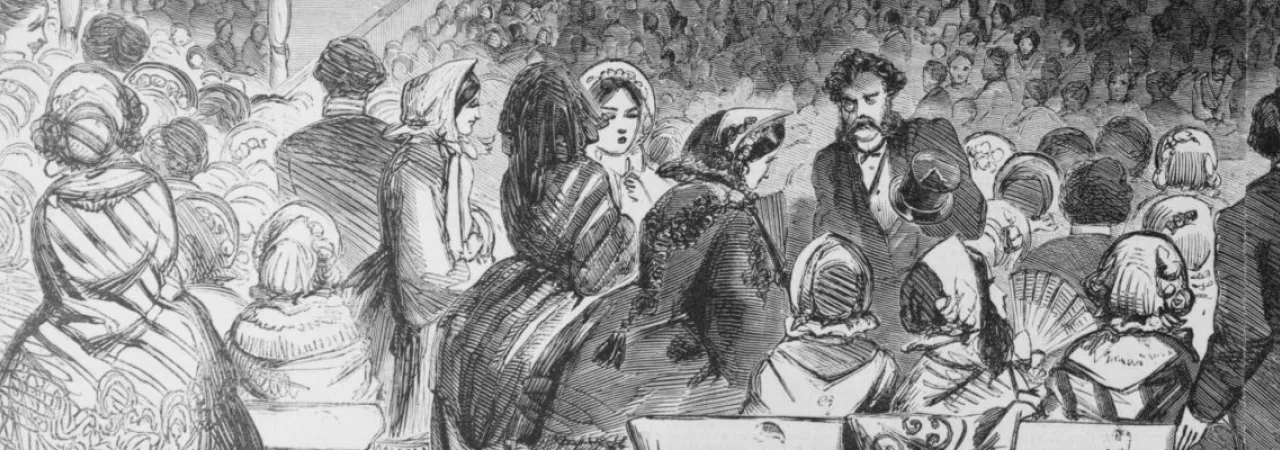

Instead of attending in person, Lincoln was represented by his friend and campaign manager, Illinois judge David Davis, whose initiative and deal-making skills, despite his candidate’s disapproval of such behind-the-scenes maneuvering, is widely credited with his eventual nomination. Davis did, however, follow Lincoln’s instruction in forming their general strategy as he maneuvered throughout the building nicknamed “The Wigwam”: to make up for his meagre resumé compared to Seward and Chase, his team thought it prudent to not go on the attack against the frontrunners and instead become “everybody’s second choice,” through the convention’s ranked voting system. His campaign also used the convention to start forging Lincoln’s image as the Rail-Splitter, a reference to his working-class background and a potential golden opportunity to appeal to the common laborers in the industrial Northern states who stood to benefit the most from the Republicans’ Free Soil ideology. They also made direct appeals to delegates from the critical swing states of Pennsylvania and Indiana. When voting began on the 18th, Davis and his allies felt confident in their chances to pull ahead. The first ballot placed Seward, predictably, with the highest vote total of 173.5, but not enough to win a majority, while Lincoln followed with a total of 102. The second round bumped Lincoln’s total number of votes to 181. The momentum on Lincoln’s side continued to surge into the third round, where Lincoln received a total of 231.5 votes, still not enough to be nominated, until David Cartter, leader of the Ohio delegation, announced his decision to switch support from Chase to Lincoln, making him the 1860 Republican nominee for President.

The nomination of a moderate candidate like Lincoln set the Republican Party’s tone for the rest of the election cycle. Just as Lincoln emphasized national unity above all else, while still decrying slavery’s role in sectionalism, so too did the party platform agreed upon by the National Committee. The document they published wastes no time invoking the preamble of the Declaration of Independence (especially the oft-repeated phrase, “All Men are Created Equal”) to assert their anti-slavery position, but the platform avoids mentioning some of the most incendiary controversies of the day by name, including the Fugitive Slave Act, Dred Scott Decision and John Brown’s recent raid on Harper’s Ferry. But the overall message it presented was one of national unity against the forces of sectionalism, and the fight against the expansion of slavery and the reduction of Slave Power was merely a means to that end, emphasizing that “to the Union of the States this nation owes its unprecedented increase in population, its surprising development of material resources, its rapid augmentation of wealth, its happiness at home and its honor abroad.” The platform did make firm stances on a few issues, such as opposition to the Lecompton Constitution in Kansas and any possibility of a revived Atlantic Slave Trade, but overall, the message the Republicans ran on was designed to be as broadly appealing as possible.

In spite of all these outreach attempts from the Republicans, many of their Democratic rivals, particularly from the Deep South, still reacted violently to the thought of a Republican president, just as they did to Frémont. In many Southern states, Lincoln’s name was not even allowed to appear on the ballot. However, in a reversal of 1856, it was the Democrats this time who managed to split the vote between several candidates. Furious that eventual nominee Stephen Douglas did not support slavery fervently enough, Southern Democrats broke from the party and nominated John Breckinridge, while John Bell’s Constitutional Union Party also threw their hat in the ring. By the end of election day, Lincoln had only managed to win little more than thirty percent of the popular vote, but succeeded in winning enough populous Northern states, trouncing his old Senate rival Douglass in most of them, to carry him to victory in the electoral college. Little over a month after Lincoln’s election, the Southern Democrats finally made good on their promise in South Carolina, where they voted to secede from the Union. In spite of all the rhetorical measures taken to avoid it at the Convention, the first Republican President had a Civil War on his hands.