In 1846, an enslaved man in St. Louis asked to purchase his freedom from his master. When she refused, the chain of events that followed would forever alter the course of events in the United States.

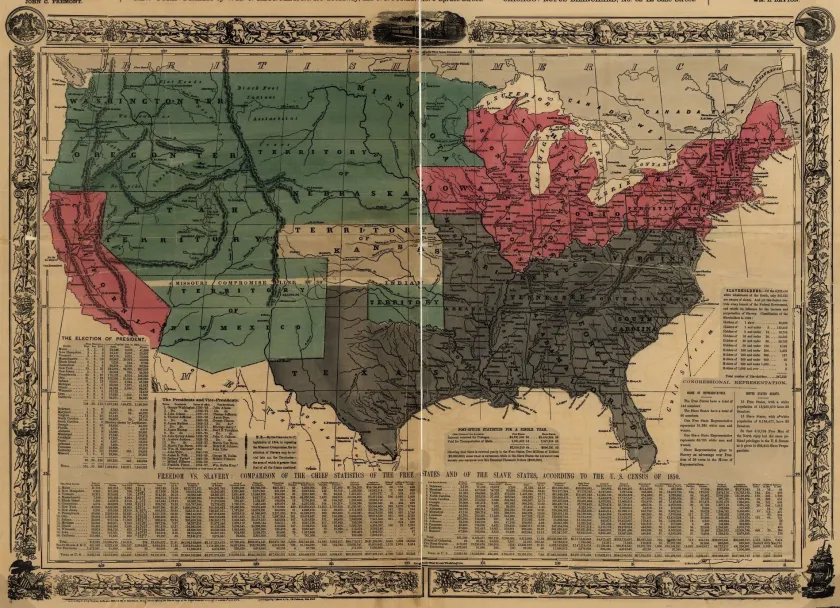

Dred Scott was born into slavery around 1799. He was enslaved by multiple owners, one of whom was an army doctor named John Emerson who brought him to different posts in Illinois and the Wisconsin Territory. Illinois was a free state as decreed by the 1787 Northwest Ordinance and the state’s constitution; the Wisconsin Territory was free because of the Missouri Compromise of 1820, which banned slavery north of the 36°30 latitude line. Scott’s prolonged stays in free territory would have given him legal standing to sue for freedom, but for unknown reasons, he chose not to do so.

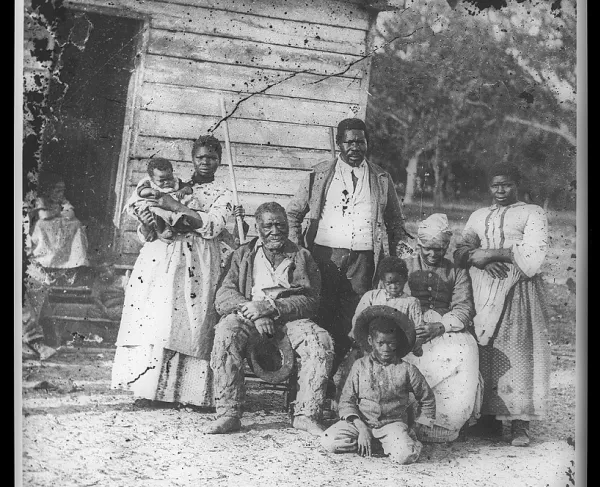

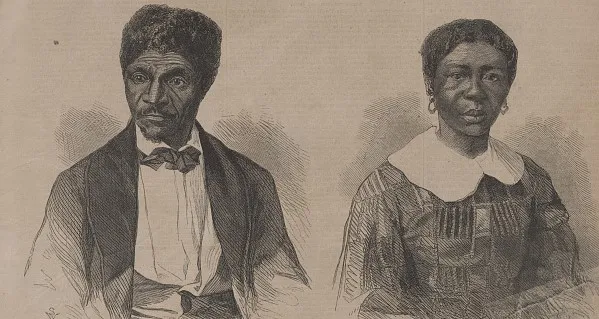

During Scott’s residence in Wisconsin, he met Harriet Robinson, an enslaved woman whom he married and with whom he had two daughters. The Scotts were then forced to return to St. Louis by their owner, where they remained until their master died in 1843. Three years later, Scott appealed to his master’s widow, Irene Sanford, and offered to pay $300 for his freedom. She refused, leading Scott to turn to the courts. Harriet played a large role in convincing her husband to sue for freedom, as she feared that their daughters would be sold away from them. Her church connections led her to their first lawyer. He, as well as Harriet, sued for freedom on the grounds that they had both spent significant time in free territory and were thus being illegally held as slaves. This was based upon an 1824 Missouri precedent known as “once free, always free.” The Scotts’ cases would be combined into one, with Dred being listed as the sole plaintiff.

The St. Louis circuit court ruled against Scott based on a technicality where the court couldn’t prove his ownership. However, the Missouri Supreme Court ordered the circuit court to take up the case again, and when it did so three years later, the court reversed its decision, ruling that the Scotts had been held illegally as slaves and were thus free. The Scotts were free for two years when the Missouri Supreme Court struck down the lower court’s ruling after Sanford appealed the decision. Missouri no longer had to abide by the laws of free states due to the growing abolitionist movements in those states, overturning the “once free, always free” precedent. Scott again sued for his freedom, this time in federal courts, but once again lost. Finally, the Scott family appealed their case to the highest court in the land, the United States Supreme Court.

In the years since the Missouri Compromise, pro-slavery forces had been looking for a way to resolve constitutional issues surrounding the admission of new states into the union. Much territory had been gained since 1820, most significantly the Mexican Cession, a large swath of land ceded by Mexico due to its defeat during the Mexican-American War. Increased tensions over whether this new territory should be free or slave nearly threatened the Union, and southern legislators wanted the courts to finally take a stand on the issue. The Compromise of 1850 had even included a provision that expedited any appeals concerning slavery in Utah, New Mexico, and eventually Kansas and Nebraska, immediately to the Supreme Court. But no cases arose, and the constitutionality of a slavery ban in the territories remained unresolved.

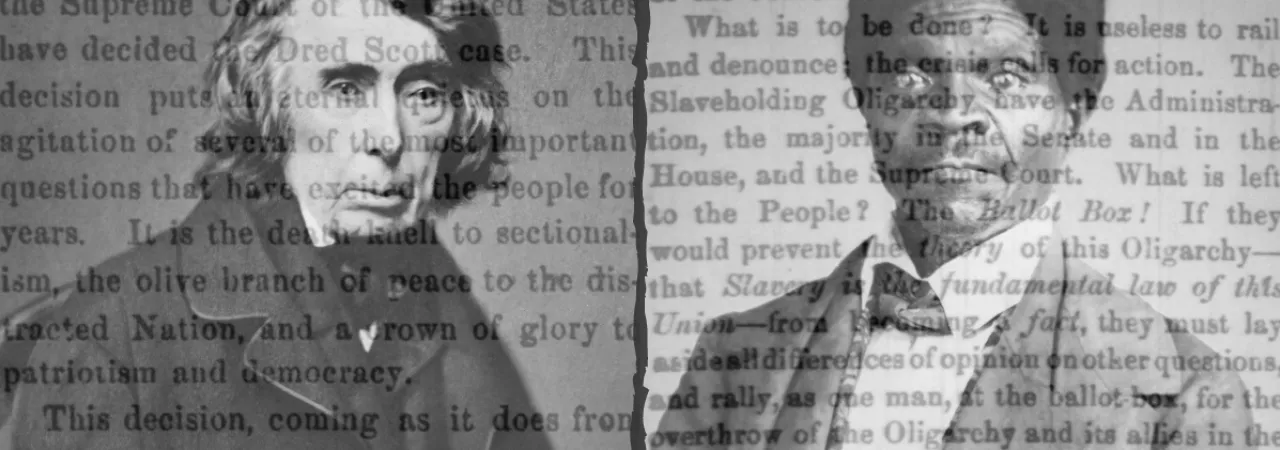

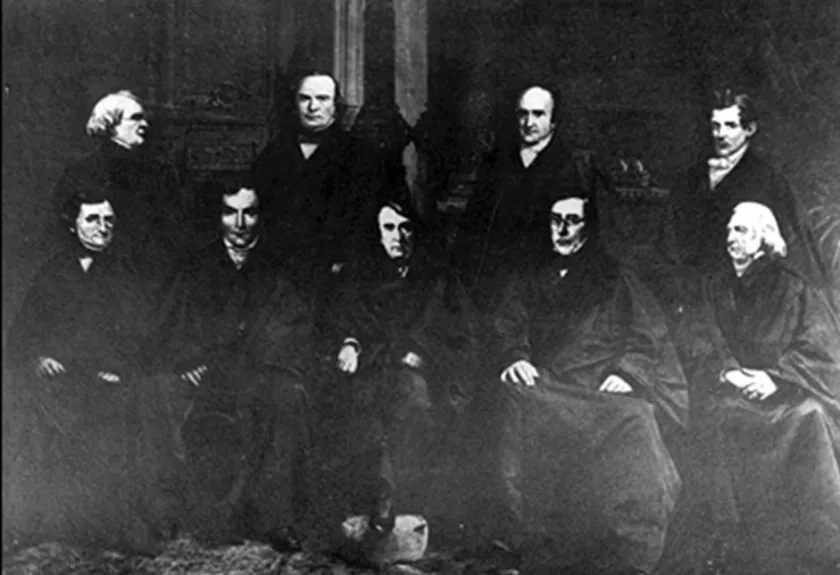

So, when Scott’s case appeared on the docket for the Supreme Court in 1857, supporters of slavery finally saw their chance to cement the institution’s place in the expanding United States. Five of the nine justices were from the South, including Chief Justice Roger B. Taney. Taney, a former slave owner, had spent most of his time on the bench defending slavery. He believed that the institution was inextricably linked to the perpetuation of Southern life and values, which he saw as increasingly under attack by Northern aggression.

However, despite this, the court originally decided to uphold the decision of the federal circuit court, saying that state law determined the Scotts’ status. They would have been using a precedent from an earlier case, Strader v. Graham (1851), which deferred to state legislation concerning the status of slaves. By only focusing on only a narrow aspect of Scott’s case, the court once again dodged controversy and avoided answering the question of whether a ban on slavery in the territories was constitutional. Justice Samuel Nelson, a Democrat from New York, began to write the opinion, but suddenly the court changed its mind and decided to write an opinion on all aspects of the case.

Beyond the question over whether Scott’s residence in free territory made him free or not, the case also begged two more essential questions: Was Scott, an enslaved black man, a citizen with the right to sue in federal courts? And was the Wisconsin Territory actually free territory? That is, did Congress have the right to ban slavery in the Louisiana Purchase? These questions, especially the latter, were much more controversial, and decisions made on them would have wide-reaching effects. For Southern slaveowners, they hoped the Southern majority on the court would finally give them vindication on the unconstitutionality of the Missouri Compromise. But Nelson’s narrow opinion dodged this controversy and avoided answering either of these two questions. Thus, one of the most infamous Supreme Court decisions in American history nearly wasn’t written.

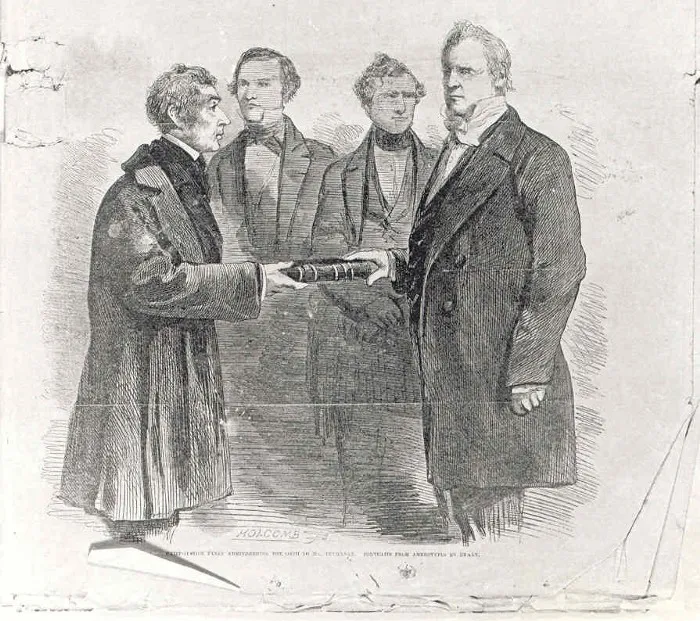

But soon after, the court reversed its stance and decided to make a more comprehensive ruling on the case. Why the sudden change? Justices Benjamin Curtis, a Northern Whig, and John McLean, a Northern Republican, decided to write a dissenting opinion and would go beyond Nelson’s narrow interpretation. In addition to granting Scott’s freedom, they would answer the two other questions of Scott’s case by affirming black citizenship and support the right of Congress to ban slavery in the territory. A traditional view of the case argues that Taney and the other Southern justices didn’t want the Northerners’ voice to be the only voice speaking about these controversial issues, so they voted to have Taney write an opinion that would encompass the three central questions. But according to historian James M. McPherson, the issue was much more complex. The Southern justices had wanted to rule on the Scott case but did not do so because they didn’t want the decision to be a sectional one. A purely sectional decision would only exacerbate tensions and would limit the decision’s power. The Northerners’ dissension was the excuse the Southern justices needed to get a Northerner into their fold. In an egregious governmental breach of checks-and-balances, President James Buchanan then pressured Justice Robert Grier, a fellow Pennsylvanian, to join the Southerners in the ruling. In the end, Curtis and McLean would be the only dissenters in the 7-2 decision against Scott.

Taney’s opinion was 55 pages long, and the majority of those pages were dedicated to answering the question of whether Scott, as an enslaved man, had the legal standing to sue in federal courts. The short answer: no. But Taney spent pages justifying a decision deeply rooted in the racist prejudices of a 19th century Southern slaveowner. He used his interpretation of American history and the Constitution itself to argue that Black people, whether enslaved or free, were not citizens in the eyes of the law, and thus Scott had no standing to sue in federal courts. The man who wrote the Declaration of Independence, Thomas Jefferson, was a slaveowner; according to Taney, this meant that when Jefferson wrote that “all men were created equal,” he was only referring to White men. Furthermore, when the framers wrote the Constitution, Black people were not part of the citizenry to be governed by the document. The inferior status of Blacks at the time of the founding, Taney argued, lasted into the present day. Curtis and McLean argued in their dissent that this argument was flawed because many Northern states had laws giving legal standing to free Blacks. But Taney asserted the Scott case was about federal citizenship, not state citizenship. By ripping away citizenship from any Black people, he denied them any of the protections guaranteed by the Constitution, the right to sue in federal courts one of them. The space Taney devoted to this issue is surprising considering the public saw this as the least of the three questions raised by Scott’s case.

The opinion could have ended here, a devastating blow already made against Black Americans. Scott’s case was no longer valid based on this logic, since as an enslaved Black man, he had no right to even bring his freedom suit to federal court. But Taney continued to answer the two remaining questions. Both contemporaries and modern historians have argued that the rest of the decision was obiter dictum, a statement on matters not officially before the court and without the force of law. Taney argued that because the federal circuit court had considered all parts of the case, all aspects of the case were also up for consideration by the Supreme Court.

Taney only wrote one page about whether or not Scott was free based on his time in free territory. No, Scott was not free. The decision of the lower court still stood; Missouri law surpassed free states’ laws in determining the status of an enslaved person.

The rest of the opinion was spent on the final and perhaps most impactful issue at stake. Was Congress allowed to ban slavery in the territories? Taney answered with a twenty-one-page response: no. His argument was based upon language. The Constitution gave Congress the power to make “rules and regulations” for the territories; to Taney, a law was not a rule or regulation. Thus, Congress could not make any laws governing the territories, only rules, and regulations. He then argues that the Fifth Amendment also forbids Congress from banning slavery at all. The amendment guarantees a grand jury trial in felony trials and protects against self-incrimination during a trial. For Taney’s purposes, however, the most important part of the Fifth Amendment is the guarantee of due process law. No citizen shall “be deprived of life, liberty, or property without due process of the law.” Based on the assumption that enslaved people were property, Taney argued that banning slavery meant depriving owners of their property without due process of the law. This was ironic considering the property at stake here were human beings without a right to due process themselves. If Congress could not ban slavery itself, nor could it give the power to any territorial governments to do so either. Any federal ban on slavery was now unconstitutional. This included the Missouri Compromise. Now, the Wisconsin Territory and the rest of the territory north of 36°30’ latitude line, had to allow slavery. Taney’s decision also killed the tenet of popular sovereignty, which argued that the residents of a certain territory should decide whether or not to allow slavery. All territory west of the Mississippi River, and whatever other territories the United States would acquire, was now slave territory.

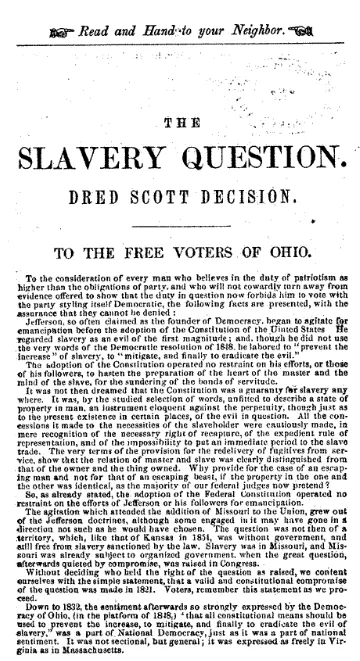

Northerners, especially Republicans, were outraged by the decision. They sided with the two lone dissenters, believing that Scott was a free man due to his time in free territory, as Congress was allowed to prohibit slavery in the territories. They contested Taney’s historical arguments with the fact that many of the founding generation had been alive during previous congressional bans on slavery, and none raised any objection. Furthermore, due process was not being violated. No slaves were being taken away from any slaveowners; they only could not take their slaves to free territory if they made the choice to travel there.

Supporters of the decision, mostly Southerners and Northern Democrats, thought the ruling would essentially neutralize the fledgling Republican party because the ruling had essentially invalidated the plank of their platform that pledged an end to the spread of slavery. However, it only energized Republicans. And even though it was three years out, they looked to the next presidential election in 1860 to right this egregious wrong. Many Republicans also believed the Scott ruling was evidence of a “slave power conspiracy,” especially between the executive and judicial branches. Buchanan’s influence on the case only bolstered these claims. One Republican, who would soon emerge as the party’s standard-bearer, feared that the decision was only the first step down a slippery slope. Abraham Lincoln believed that it was possible the decision could be used to make free states into slave states; if Congress could not ban slavery in the territories, how could Northern states ban it too? Many Northerners would come to subscribe to this notion and the Republican Party would ride Northerners’ outrage to victory in the election of 1860.

The decision also had the converse effect of damaging Democratic party unity. Northern Democrats had been strong supporters of popular sovereignty, which was also rendered null by Taney’s decision. However, leading Northern Democrats like Senator Stephen Douglas were able to somehow reconcile their beliefs with the ruling. Southern Democrats believed the decision should be taken further. It was not enough to simply say Congress wasn’t allowed to ban slavery in the territories. Slavery itself needed federal protection, enforced by the military.

Far from resolving the issue of slavery, the ruling only heightened tensions in an already divided nation. The sectional breach between Northerners and Southerners only widened, even as Southerners celebrated their victory and Northerners railed against the slave power conspiracy. For the millions of enslaved people residing in the South, this decision dealt a devastating blow. Although many at the time could not have known it, the Dred Scott decision was one of the last way stations on the road to civil war.

Scott never lived to see the bloodshed that broke out less than four years after the Supreme Court ruled against him. Although he and his family were granted their freedom, Scott died of tuberculosis in 1858. Ironically, he passed away on September 17, exactly four years before the bloodiest day in American history at Antietam would urge President Lincoln to issue the Emancipation Proclamation.

Further Reading

- The Dred Scott Case: Its Significance in American Law and Politics By: Don E. Fehrenbacher

- Dred Scott v. Sandford: A Brief History with Documents By: Paul Finkelman

- Battle Cry of Freedom: The Civil War Era By: James M. McPherson

- Before Dred Scott: Slavery and Legal Culture in the American Confluence, 1787–1857 By: Anne Twitty