Fall foliage graces the grounds at Kings Mountain National Military Park, Blacksburg, S.C.

With a common enemy, backwoods hunters and fighters united to chase down Redcoat Major Patrick Ferguson and his Loyalist army. Trekking more than 300 miles over mountains and rugged terrain, this ragtag bunch of Patriots ultimately found their target at Kings Mountain.

Between October 10-13, 1780, a report arrived for General Lord Charles Cornwallis that changed the course of the American Revolution. Cornwallis, who had spent sickness-riddled weeks at his headquarters in Charlotte, North Carolina, was anxiously awaiting word of the left wing of his army, last known to be somewhere in the foothills of the Blue Ridge Mountains. A returning patrol confirmed the rumors: Major Patrick Ferguson’s force had been destroyed at Kings Mountain on October 7.

But just who had defeated Ferguson? These backcountry Patriots were unusual, their homes were spread across what are now five states: Georgia, South Carolina, North Carolina, Tennessee and Virginia. Most were frontiersmen whose wartime experiences were limited to clashing with Indigenous warriors and Loyalist neighbors rather than British regulars. These men followed the same familiar faces who led their communities in peacetime and carried their meager food in bags hanging over their saddles.

Immediately after their victory, they faded back toward the western mountains and away from possible British pursuit, unaware of the impact they had made. The British “Southern Strategy” that had successfully pushed troops north through Georgia and the Carolinas for the past year had been thwarted by backwoodsmen and sent the British retreating into South Carolina. Never again in the American Revolution would so many Patriot militias cooperate to accomplish a singular task: stop Patrick Ferguson and destroy his Loyalist army.

They were after Ferguson specifically. In summer 1780, as British “Inspector of Militia,” he had led a force of Loyalist militia through western South Carolina. These men had fought bloodily against their Patriot neighbors since 1775 but needed leadership to be truly effective, and Ferguson, who had experience with unconventional missions, organized them to protect the left side of the British advance northward. By September, a combination of crushing British victories and Ferguson’s persuasive leadership had recruited almost 4,000 men into Loyalist regiments and driven most remaining Patriots into hiding in the mountains. Ferguson realized he could not force these people into obedience and understood the importance of winning their hearts and minds if he was to establish a foothold in the mountains. He marched northwest into North Carolina and continued recruiting his army, establishing a network of spies and distributing proclamations to Loyalists and Patriots alike. One of these proclamations was given to a Patriot prisoner named Samuel Phillips, who was freed with orders to carry it to his Patriot leaders. Philips traveled deep into the mountains of east Tennessee and brought news of the approaching Loyalist army to one of the most influential Patriot partisan officers, his distant cousin Colonel Isaac Shelby.

Most Patriots in the Blue Ridge Mountains were occupied with their own concerns when Isaac Shelby began organizing a force to oppose Patrick Ferguson. The backcountry settlements in what is now east Tennessee and southwest Virginia had fraught relationships with the neighboring Cherokee and Shawnee Nations that required constant vigilance, lest Loyalist neighbors agitate them into war. Shelby’s request highlighted the necessity of cooperation: Ferguson needed to be stopped before he reached their settlements, but no Patriot leader was strong enough on his own. The plan was to combine men from across the backcountry and strike Ferguson before he could reach deeper into the mountains. Isaac Shelby and John “Nolichucky Jack” Sevier contributed more than 400 men from the mountainous northeast corner of Tennessee. Nearly 400 more men from the southwest corner of Virginia were led by William Campbell. The McDowell brothers, Charles and Joseph, brought 200 refugees Ferguson had chased from back east. Calls for aid were sent to Patriots on the Yadkin River in North Carolina under Joseph Winston and Benjamin Cleveland, men who had reputations for aggressive pursuit of Loyalists. These groups of frontier hunters and fighters recognized that Ferguson was different from the enemy they had pursued before: a smart, veteran British officer who would soon either be too strong to attack or safely out of their reach. Speed and surprise were critical for their plan to work.

On September 25, 1780, 1,000 “Overmountain” Patriots left Sycamore Shoals (today a state park in Elizabethton, Tennessee) and began climbing the rain-soaked western slopes of the Blue Ridge Mountains. Ferguson’s spies brought him the Patriots’ names and numbers, and news of their cooperation within days of their gathering. Ferguson, however, misjudged their route, assuming that this Patriot force would swing north through southern Virginia before descending along the eastern side of the Blue Ridge Mountains. Instead, the frontiersmen climbed through Yellow Mountain Gap on the border of North Carolina and Tennessee, the highest altitude seen by soldiers during the American Revolution. At 4,649 feet, the rain became snow four inches deep, and the Patriots crossed the future path of the Appalachian Trail before descending the eastern slope into what is now Spruce Pine, North Carolina. While risky and challenging, this mountain trail shaved days off their journey and spoiled Ferguson’s expectations.

While the Overmountain men descended, Yadkin Valley Patriots moved southwest toward the appointed meeting spot at Quaker Meadows (present-day Morganton, North Carolina). Their small but fierce band grew steadily as they traveled, reaching 400 fighters by the time they arrived on September 30. Ferguson welcomed his spies’ reports of these movements. Throughout the summer, his biggest challenge had been chasing the small bands of mounted Patriot militia that were now willingly massing into a single target. Ferguson requested cavalry reinforcements to ensure victory and began to consolidate his forces for the anticipated fight.

The Patriots knew they needed to strike quickly and split as they navigated through the Gillespie and Hefner Gaps to descend to the Catawba River and Quaker Meadows, where they joined the Yadkin Valley men to create an army nearly 1,500 strong. After a night of much-needed food and rest, the army resumed its pursuit south on the morning of October 1. Torrential rains stalled their progress for nearly two days, giving them the chance to strategize. The Patriot colonels recognized that no one man had authority over their army, a potential cause of confusion in combat. Shelby proposed William Campbell as their leader: Campbell had traveled the farthest and brought the most men, and the Virginian would not cause jealousy among the many North Carolinians. Campbell reluctantly accepted command but insisted that a group council be held before any large decision. This now-united force continued south to Ferguson’s last known location at Gilbert Town (now an archaeological site in Rutherfordton, North Carolina), but found the settlement deserted. The heavy rains had erased any tracks, and these Patriot hunters feared their prey had escaped.

On October 5, the thin line of starving horses and rain-soaked men stretched along the mud trails with no sign of Ferguson. They camped that evening at Alexander’s Ford on the banks of the Green River, not far from the South Carolina border, and the Patriot commanders decided they could risk only one more day of searching for Ferguson’s trail before abandoning their plan. Out of the dark quiet, horsemen thundered into camp bringing news to their leaders: Another force of approximately 500 Patriot militia had gathered to join in the pursuit and, better yet, they knew Ferguson’s location. These critical reinforcements were Carolinians and Georgians led by James Williams, William Chronicle, Edward Lacey and William Hill — some of Thomas “The Gamecock” Sumter’s best junior officers.

These groups met the next night at Saunders’ Cowpens, a well-known cattle pasture later to become its own famous battlefield. Barely had these forces begun to rest when spies arrived, confirming that Ferguson was about 30 miles east on the road toward Charlotte. If the efforts of these nearly 2,000 Patriots over the past 13 days and 300+ miles were to mean anything, Ferguson had to be stopped before reaching the city. But the Patriots were exhausted; days of marching and riding with no food and little rest had taken their toll. Storm clouds once again darkened the western sky as each commander walked among his men, selecting the best fighters and horses to continue the pursuit. Only 900 hand-picked men mounted in the pouring rain to continue down the dark trails.

Daybreak on October 7 found these Patriots miles away from Ferguson’s campsite. Isaac Shelby scolded the men when they suggested rest, reminding them of their determination to see this job finished. As these horsemen drew closer, additional information about Ferguson’s camp came from unexpected sources: released prisoners, locals who had taken Ferguson food and Loyalist messengers. Intercepted letters revealed that Ferguson knew of his pursuers and painted a clear picture of what the Patriots could expect to find: The sought-after Redcoat had a strong position on a rocky ridge called “Kings Mountain,” beside the road to Charlotte, and he hoped to rest his men and buy time until reinforcements arrived. He did not know that his calls for aid had failed.

When the rain finally relented on the afternoon of October 7, 1780, Ferguson and his army of more than 1,000 Loyalists faced another kind of storm: a deadly ring of Patriot riflemen.

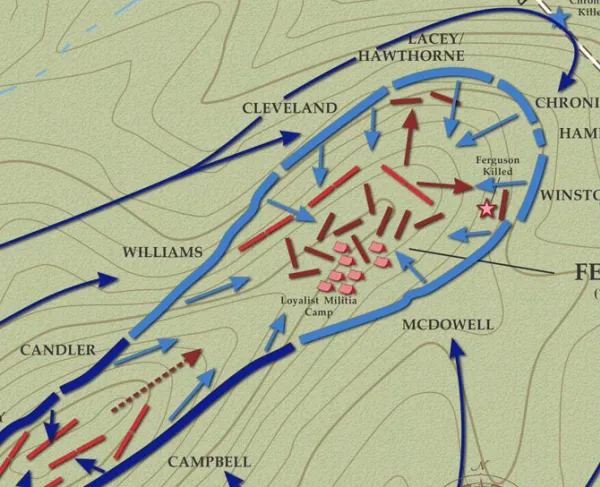

The battle was decided in little more than an hour. The Loyalist position was assaulted on all sides by Patriot frontiersmen, who used the heavy woods as cover to pour streams of fire into the defenders. Several times the Loyalists pushed the Patriots back with bayonets, only for the Patriots to return up the wooded slopes. Eventually, the Loyalists exhausted their ammunition, and their formation began to break. Ferguson led a final charge to break through the Patriot backwoodsmen, but nine shots threw him from his saddle. The Loyalist defenders broke, and chaos ensued as surrendering men became targets for revenge. By 4:30 p.m., Ferguson and nearly his entire Loyalist army was destroyed.

The swiftness of the Patriot pursuit, the brutality of their attack and the prisoner executions over the following weeks shattered the fighting spirit of most southern Loyalists. The Overmountain Men disappeared as rapidly as they had arrived, but rumors of their presence threatened every British outpost. Cornwallis moved back into South Carolina, buying the Patriots time to rebuild the southern Continental army. Today, the 330-mile trail used by these Patriots is preserved as the Overmountain Victory National Historic Trail, a motor route with a growing network of hiking trails stretching across four states. It is dedicated to protecting the route and sharing the story of how an army of backwoods hunters and fighters shared command, cooperated with their neighbors and created a stumbling block that saved the American Revolution.

Related Battles

90

1,018