Did you know that many of your classic childhood songs have historical roots? Nostalgic tunes such as “Yankee Doodle” and “Home on the Range” are not only catchy but reflect national attitudes during significant events in American history. Often, these songs served as responses to the wartime activities the United States became embroiled in. While the exact origins of many of these tracks are unknown, their impact on American culture and memory have cemented them as the songs of the nation.

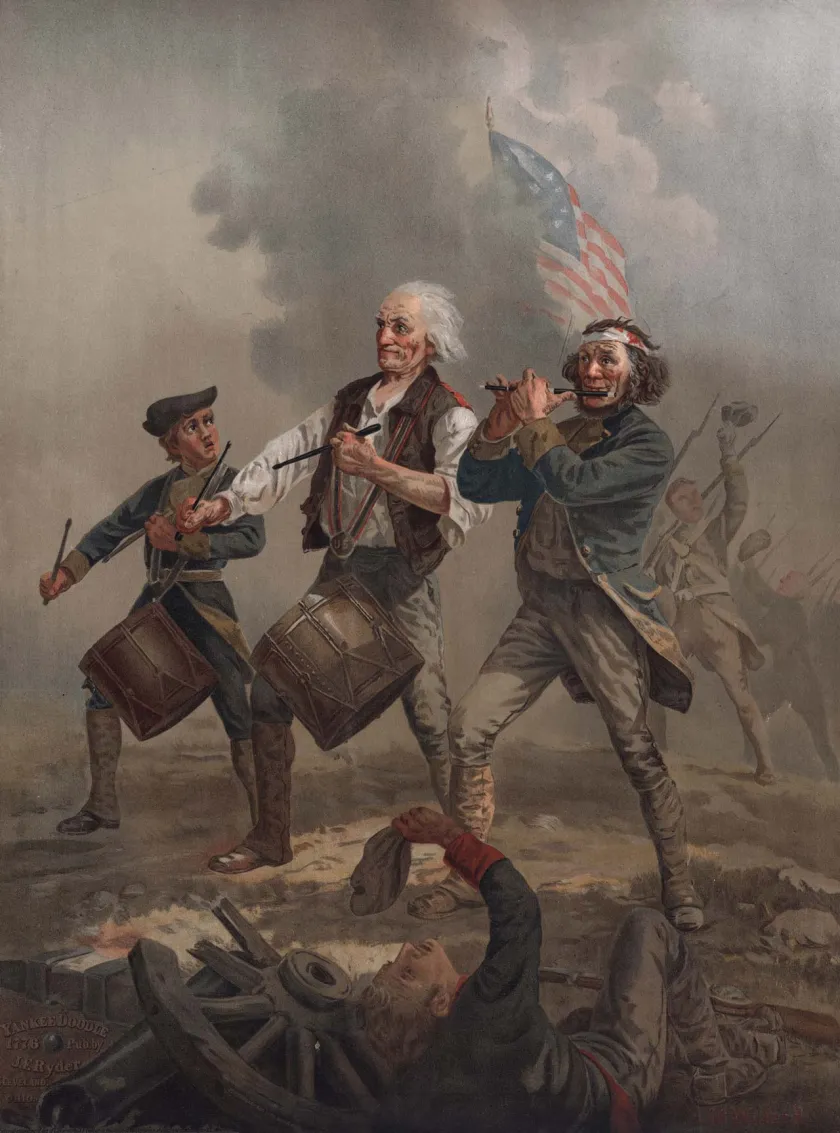

“Yankee Doodle”

What initially began as an insult by British soldiers towards American colonists swiftly became a rallying cry during the Revolutionary War. The French and Indian War (1754-1763) brought British troops across the pond, where they fought alongside colonial forces. However, the two groups did not always get along. Penned by a British doctor in 1755, “Yankee Doodle” served as a mocking taunt, referring to American men as country hicks (“doodle”) and conceited jerks (“dandy”).

The tune was still popular when the Minutemen fired “the shot heard around the world” at Lexington and Concord. British army musicians allegedly played “Yankee Doodle” as they marched into the Massachusetts town mocking their inexperienced opponents. However, as the colonial militiamen beat them back into retreat, the Americans began tauntingly singing the tune, reclaiming the insult. “Yankee Doodle” quickly became the unofficial anthem of the Continental Army.

The song was also famously played at Yorktown — the decisive engagement and Patriot victory that spelled the end of the Revolutionary War. When the Redcoats marched out to surrender, they refused to acknowledge their American opponents and instead marched with heads pointed solely toward the French troops. Outraged by this disrespect, the Marquis de Lafayette — commander of the Light Infantry brigade — ordered his band to play “Yankee Doodle.”

As the fifes and drums blasted the tune, British soldiers finally turned to acknowledge the Patriot victors. Today, "Yankee Doodle” is the official state song of Connecticut and a staple song in American culture.

“Battle Hymn of the Republic”

Penned during the throes of the Civil War, the “Battle Hymn of the Republic” may very well be one of the most recognizable songs in the nation.

The melody stems from an old folk hymn called “Stay Brothers, Will You Meet Us” — with its well-known “Glory, Hallelujah" chorus. With religion as an integral aspect of everyday life and community, spiritual music was a part of daily routines. While the songs often evolved — changing lyrics and titles — they retained similar structures and notes. The “Battle Hymn of the Republic” became a natural progression of this.

As America dissolved into civil war, the lyrics of the familiar hymn shifted. The formerly named “Stay Brothers, Will You Meet Us” morphed into “John Brown’s Body.” Although initially named after a Scottish Union soldier, the marching song quickly became associated with the famous abolitionist leader hanged at Harpers Ferry. The tune became a rallying cry for Northern troops during the early years of the war.

The song went through another transformation after poet Julia Ward Howe toured Union army camps near Washington, D.C., with Reverend James Freeman Clarke and with her husband, Dr. Samuel Gridley Howe in November of 1861. During the visit, troops sang “John Brown’s Body,” prompting Reverend Clarke to suggest that Mrs. Howe set new lyrics to the tune. Her new lyrics first appeared on the front page of the Atlantic Monthly in February of 1862 after she received $5 for the piece.

A fierce abolitionist, Howe's lyrics set the northerners on the right side of the conflict and managed to target slavery. One of her verses included the words “let us die to make men free.”

Editor of the Atlantic Monthly, James T. Fields, is credited with having dubbed the song the “Battle Hymn of the Republic.” Today, this historical melody is still part of protests, church services and sporting events, cementing itself in the American psyche.

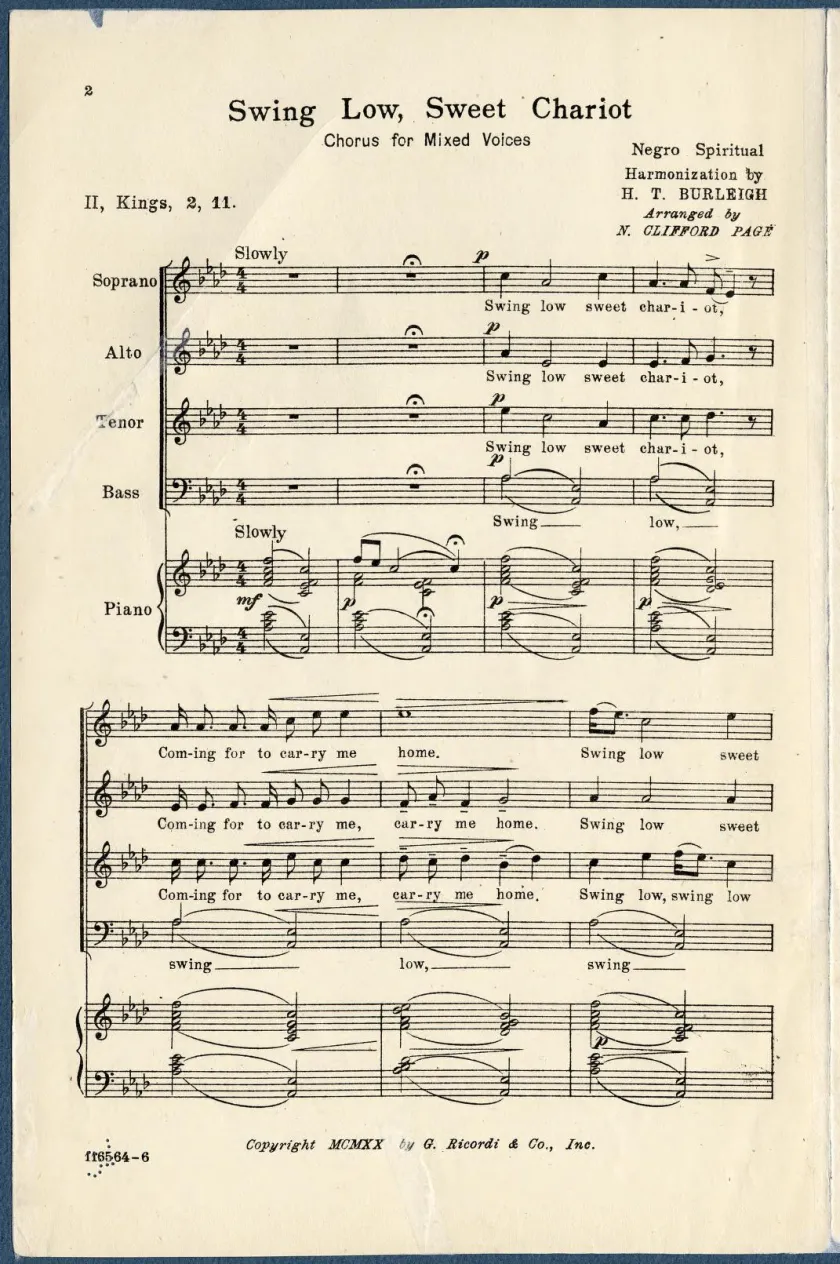

Popular with English rugby and choirs alike, “Swing Low, Sweet Chariot” is an American folk classic. Whether you heard this iconic song in a film, TV show or a high school music class, its melody is immediately recognizable. “Swing Low” began as a spiritual, a genre sung by enslaved individuals in the South. Usually sung in a call-and-response pattern, these songs became a way for the enslaved to express their faith, sorrows and hopes for emancipation.

“Swing Low, Sweet Chariot” is often attributed to Wallace Willis, a Choctaw freedman who is said to have composed the song sometime in the 1860s. However, like most folk songs, the lyrics and tune were most likely a group effort, passed down by generations of enslaved people. The chorus, repeating lines of “swing low, sweet chariot, coming to carry me home,” promises an escape — to freedom or heaven.

Union victory at the bloody Battle of Antietam on September 17, 1862, paved the way for President Lincoln to issue the Emancipation Proclamation, which freed the enslaved in the states that had seceded from the Union. For many of the enslaved, this was their promised “chariot,” which finally brought them to freedom.

The song found a resurgence in the 1960s during the civil rights movement and became popularized by famous singers such as Joan Baez, Dolly Parton and Johnny Cash. The song's captivating tune and meaningful lyrics have secured “Swing Low, Sweet Chariot” a spot as one of the most famous American folk songs.

“Home on the Range”

“Home on the Range” is one of the most recognizable songs of the American West. Written by Kansas homesteader Dr. Brewster M. Higley, the number celebrates the beauty of the open plains. Surprisingly, Higley’s original version does not contain the words “home on the range” at all! Like most folk songs, the tune went through several iterations before becoming the beloved melody that we know today.

Higley moved out west as part of the Homestead Act of 1862. Passed during the Civil War, the law allowed any adult citizen who had never borne arms against the U.S. government to claim 160 acres of surveyed government land so long as they lived and worked the plot.

Potential homesteaders flocked westward after the Civil War, eager to start a new life and make something of themselves on their land. This new opportunity gave Civil War veterans special privileges, allowing them to settle even if they did not meet the requirements of being over 21 years of age. Although Higley did not serve, his verses describe the beautiful views that many veterans saw out on the plains. After hearing the song from a Black barkeep in San Antonio, Texas, famous folklorist John Lomax recorded his version in 1908 — adding the famous “home on the range” lyrics. Today, the tune is the state song of Kansas and has become synonymous with the American West.

Next time you find yourself humming one of these nostalgic tunes, try to remember what the lyrics say. You may just find that they have a richer history than meets the ear!