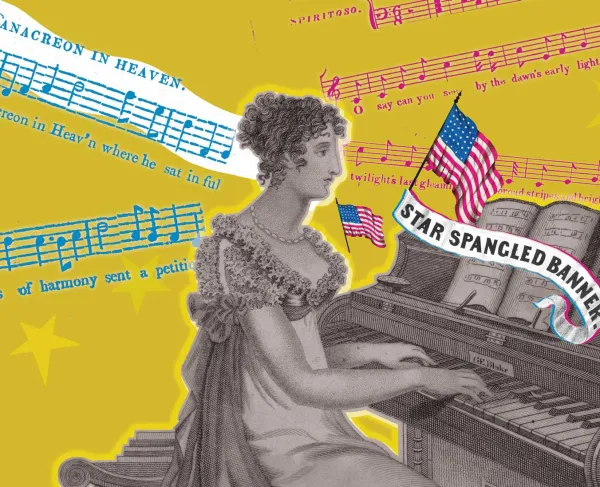

Popular Music of the Revolutionary War Period

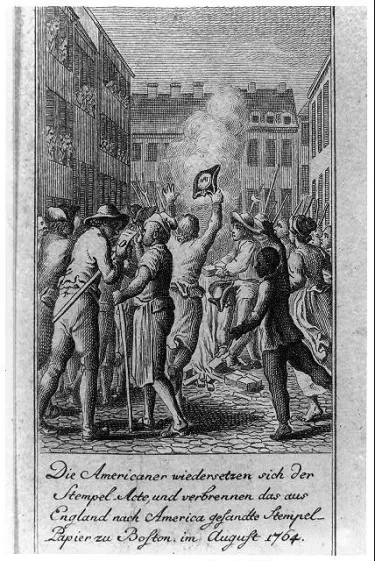

With a population of nearly 1.5 million and growing, the Thirteen Colonies expanded rapidly by the late 1750s. The Industrial Revolution was underway, and an influx of immigrants from Ireland, Scotland, Italy, and England provided plenty of workers to fill the growing numbers of manufacturing jobs. As more areas of the colonies moved away from their agrarian roots, their dependence on manufactured goods from British Empire waned. At the same time, there was a shift in domestic production in the colonies, there was also an ideological one, a desire for independence from the tyrannical motherland. As England imposed taxes such as the Stamp Act of 1765, the Townshend Acts of 1767, and the Tea Act of 1773, so too did the ire of the colonists. Against this backdrop was a rich and diverse musical landscape composed of influences from numerous countries and traditions. And, as the individual colonies moved toward a singular country, so too did a uniquely American soundscape.

This period of immense change in the colonies was also seen in the world of music. In Western art music, the Baroque Period, lasting from approximately 1600-1750, neared its end. Known for famous composers such as Johann Sebastian Bach, Antonio Vivaldi, and George Frideric Handel, these composers were masterful creators of melodic lines, elaborate decoration thereof, and numerous pieces for chamber ensembles. Of these, it was Bach who was the forerunner of his time in Baroque composition. Known for his solo suites and organ works, Bach’s repertoire spanned both the sacred and secular. One of Bach’s most famous works is the Toccata and Fugue in D Minor, BWV 565, written for organ. Requiring a high caliber performer, the piece’s opening melodic lines have stuck in the listener’s ears for generations. The toccata explores the wide range of the organ, requiring the performer to explore the far octaves of the instrument with great precision and musicianship. The fugue section consists of four voices and is written entirely in sixteenth notes. The constant movement of all four parts and the solo pedal line that is introduced provides a stark contrast to the opening portion of this work. Bach’s works, including his Toccata and Fugue in D Minor, have stood the test of time and are still considered some of the most essential compositions of this musical time period. Undoubtedly his works would have still been played and heard both in the colonies and Europe during the immediate lead up and war itself.

But the music of Bach signified an older era of compositional timbres and techniques. As concert halls became more popular around the world, there was a natural shift in the type of music that could be performed in this new setting. As most Baroque music was originally composed for sacred purposes as well as small social gatherings, a new era of musicians and composers now needed to reach the social audience who was helping music of the time period become a serious art form. Additionally, the very composition of the ensembles that performed these works was changing. More instruments were being added to the scores, such as clarinets, bassoons, and additional brass instruments like the trombone (sackbut). The Classical Period was born, and with it, national pride in fostering and promoting native musicians and composers and more accessibility by the commoner.

Some of the many composers during the Classical Period were Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, Ludwig van Beethoven, and Joseph Haydn. These men, along with countless other composers and musicians, were musical geniuses that paved the way in the new genre of symphonic composition. Symphonies, extended musical works native to Western art music, are usually written for a large orchestra. Orchestras of this period consisted of a string section, woodwind section, brass section, and a percussion section. In total, an orchestra could range from approximately 30 to over 100 musicians. This was a drastic change from the typical chamber music setting that was so popular during the Baroque Period. All symphonies are composed of multiple movements, usually four, that vary greatly in style and tempo. Most commonly, the first movement is composed in sonata or allegro form, the second movement in a slower tempo, the third movement in the style of dance (minuet or scherzo), and finally the fourth movement a rondo or an allegro. It should be noted, however, that there were many variations on the above-mentioned forms which allowed composers to express their creativity.

Of the many notables of the period, the short life and incredible musical contributions of Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart must be highlighted. As a young child prodigy living in Salzburg, Mozart excelled at the piano and violin and performed for European royalty at a very young age. After a trip to Vienna, Mozart chose to stay there and immerse himself in its musical culture. It was here that he started composing symphonies, concertos, and operas. One of his most famous symphonies is No. 40, G Minor, K. 550. This work was completed in mid-1788 and consisted of four distinct movements. These movements include the Allegro, Andante, Menuetto (trio), and Finale.

In the colonies, colonists were exposed to a completely new listening experience performed by symphonic orchestras in large, grandiose concert halls. New York, Boston, and Philadelphia were just a few large cities among the northern colonies that offered a thriving musical experience for citizens. Ranelagh Gardens was opened in 1766 in New York City and was patterned after London’s pleasure gardens. The Ranelagh Gardens offered daily musical performances and dance gatherings. Furthermore, instruments were now more readily available for purchase by the commoner. Colonists who resided in larger cities could purchase an instrument and all necessary accessories at their local music store. Advertisements were printed and distributed to promote new musical instruments such as the French horn and the hautboy, which was the predecessor to the modern day oboe. If they so desired, musical tutors such as Charles Love advertised his musical instructional services as “teaches gentlemen the violin, hautboy, German and common flute, bassoon, French horn, tenor and bass viol.”

Although the Classical Era of Western art music expanded across Europe and England to larger audiences of more social classes, accessibility to these popular musical traditions were far less to those living in the American colonies. Despite the small growth of large concert halls in the northern colonies, they did not become a part of American music culture until the beginning of the nineteenth-century; and, since music was unable to be recorded at this time in history, live performances and concerts were the only real way to be immersed in this genre of music. Thus, music in the colonies looked far different on composition paper than the great composers of the Baroque and Classical eras. For many, it was songs performed by one or a few musicians at taverns or gatherings with more personal meanings that were heard the most by the commoner during this period.

Colonists often wrote and performed music that spoke to their daily lives. Utilizing common household instruments of this period such as harpsichords, violins, and flutes, small gatherings allowed for the sharing of music among friends and family. Music was also a way for colonists to keep their cultural traditions and customs alive and thriving in the new world. Many musical traditions lived on through cultural holidays. Dutch settlers in the colonies, for example, continued to celebrate the Christian feast day, Pinkster, or as the English called it Whitsunday. Pinkster was also viewed as a day that represented the coming of spring. The tradition consisted of Dutch children parading around town to “awaken” spring. The townsfolk would open their windows and doors to signify their acceptance of the new season. If a household did not open their windows and doors, they would sing the song “Luilak” which translates to lazybones.

As frustrations grew between the colonies and the Crown, often these small concerts included music that spoke to their audience’s grievances. Songs about the lack of representation in Parliament and mocking English leaders became popular. An example of this type of colonial music can be found in the song “A Taxing We Will Go.” The imposition of the 1765 Stamp Act outraged the colonists as they felt they were receiving “taxation without representation.” The lyrics specifically focused on the topic at hand, noting “The power supreme of Parliament our purpose did asist[sic], and taxing laws abroad were sent, which the rebels do resist…."

As war settled across the colonies, the role of music in the daily lives of soldiers and civilians only increased. Music was heard in several ways by both officers and men of the Continental and British armies. Music was a way to provide calls and commands while on the march, in camp, or on the battlefield. Musicians could easily play over the loud sounds of battle providing troops with cadence marching and even tactical signaling. Drummers were one of the most important musical positions that could be held within a military band or unit. After enlistment, drummers were required to learn and memorize numerous rudiments or beats to utilize throughout each day in camp, while on the march, and in battle. One of the most well-known rudiments from the American Revolution is “Reveille.” It was to be played each day at daybreak to alert the soldiers to “rise and comb his hair and clean his hands and face and be ready for the duties of the day” as well as the cessation of challenging by the guard. The drums that sounded these rudiments were made of a wooden frame and top and bottom “heads” made of calfskin or sheepskin which were then stretched over the frame. To create tension and to assist with tuning, ropes were laced through holes drilled into the wooden frame. Additionally, four to six strands of catgut or rawhide were stretched across the bottom center of the drum head to create snares. Drums were not the only important sound on the musical landscape within both armies, however.

The fife was also a key instrument during the American Revolution. With its loud projecting capabilities, the troops were able to hear this instrument over the sounds of an army on the march or the cacophony of battle. A popular song of the era that prominently featured this instrument was “Yankee Doodle.” Still widely-known today, it gained its familiarity in the American musical consciousness during the American Revolution. Originally, this tune was sung by British military officers as a way to mock the sad state of the colonists and their army. The colonists embraced this mockery and it provided them with a sense of camaraderie and patriotism. To the surprise of many British officers and enlisted men, Washington’s men turned the derogatory implications of this song around and used it as a song of defiance and pride. Thus, “Yankee Doodle” rose to be a song of not just colonial, but national acclaim.

In the British army, a popular military song that soldiers heard during the American Revolution was “The British Grenadiers.” A traditional marching song that was set to a tune dating back to the seventeenth century, it refers to a specific type of British soldier known as a grenadier. This type of soldier was utilized by the British army beginning in the mid-to-late seventeenth-century with one of their sole tasks to throw grenades at the enemy. The British army always chose the largest most able bodied men to be Grenadiers. As time and military advancements evolved, the use of grenades became unnecessary. However, the British army still chose soldiers to be Grenadiers. It was an honor for soldiers to be chosen to uphold this esteemed position. The song was a way for the British army to honor and encapsulate the true patriotism of all British troops.

The Revolutionary War period was an era defined by immense change. An influx in immigration, a rapidly growing population, a shift in gross domestic products, and philosophical and ideological divisions with the laws and politics of England within the colonies are only some of the many changes witnessed by those who lived through this turbulent time. Music during the Revolutionary War era was no exception when it came to change. The Baroque Era had ended and gave way to the Classical Era. Songs and music about the colonist’s daily lives gave way to reflect their growing frustrations and mood towards England, independence, and war. With that change came new musical soundscapes as colonists entered the army and British armies occupied and moved through vast sections of the colonies themselves. Military music and musicians thus entered the colonial musical scene. The confluence of all this social and cultural change spawned a new, rich, and diverse musical landscape that continued to solidify as the war gave birth to a new nation, and with it, pieces of music that remain popular until today.

Further Reading

-

The History of Modern Music By: J. Peter Burkholder, Donald J. Grout, and Claude V. Palisca

-

Music of the Civil War Era By: Steven H. Cornelius

-

America's Musical Life By: Richard Crawford