A sketch by Alfred Waud, showing the Confederate fleet breaking through the barrier at Trent's Reach

By January 1865, Lt. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant’s armies in Virginia had a choke hold on the Confederate railroad center at Petersburg and the capital city of Richmond. The stalemate began six months earlier as Grant’s forces confronted Gen. Robert E. Lee’s defenders and dug into a series of ever-lengthening trench works. Grant’s front reached from the east bank of the James River outside Richmond across the river to the western edge of Petersburg. One possible weak spot in the Union line got the attention of Confederate war planners: Grant’s supply base and military railroad head on the river at City Point. All of Grant’s reinforcements, ammunition, and food were offloaded by ships at the docks there. If a river-borne force of ironclads and gunboats could descend the river from Richmond and destroy City Point, Grant might be forced to fall back. Flag Officer John K. Mitchell, who had commanded the James River Squadron since the previous May, was put in charge of the effort. The Confederate government was optimistic about Mitchell’s success. Secretary of the Navy Stephen Mallory told Mitchell on January 21: “You have an opportunity, I am convinced, rarely presented to a naval officer, and one which may lead to the most glorious results to your country.”

John Kirkwood Mitchell was born in 1811 in Wilmington, North Carolina. He joined the navy when he was 14 and graduated from the Naval Academy in 1831. In April 1862, now a captain in the Confederate navy, Mitchell was given command of the Rebel flotilla defending New Orleans, centered on the not-yet-completed ironclad ram CSS Louisiana. After Flag Officer David G. Farragut successfully ran past the forts and ships guarding New Orleans and captured the city, Mitchell’s inefficient deployment and preemptive scuttling of the Louisiana were partly blamed for the defeat. He surrendered to Farragut in New Orleans and was exchanged in August 1862. Mitchell’s next assignment was a desk job in the Orders and Detail branch of the navy department in Richmond. He became commodore of the James River Squadron in May 1864.

John Kirkwood Mitchell, Confederate Captain of the James River Squadron. Picture Courtesy of the Navy History Division of the Navy

The role of the James River Squadron was to defend Richmond from Union warships. The number of craft, most of them lightly armed wooden tugboats, cargo boats, and passenger ferries, varied during the war but was never more than about a dozen vessels. All were steam-powered. The CSS Virginia, supported by two vessels from the squadron, sank or burned two Union warships and grounded three more on March 8, 1862, before the ironclad USS Monitor could intervene the next day. After the Virginia was scuttled with the evacuation of Norfolk two months later, the squadron was withdrawn to Richmond, giving the Union navy access upriver as far as Drewry’s Bluff, just nine miles from the capital. CSS Virginia’s incursion into Hampton Roads showed the Confederates that ironclads could be helpful against Union wooden warships and could at least fight the monitors to a draw. The first of their new ironclads, CSS Richmond, was laid down at Gosport Navy Yard within weeks of the Virginia-Monitor duel. Richmond was designed by John L. Porter, who had built up Virginia from the burned-out remains of the USS Merrimack. Richmond was several hundred tons lighter, carried four Brooke rifled guns, and drew only 13 feet of water. After the fall of Norfolk, the Richmond was evacuated upriver to the Rockett’s Landing shipyard on the southeast edge of her namesake city. Porter designed two more ironclads, identical to Richmond, laid down at Rockett’s Landing, and became the CSS Virginia II and CSS Fredericksburg. Both also carried four guns each and were commissioned in 1863 and 1864.

The onset of Grant’s Overland Campaign in early May 1864 saw a dramatic increase in activity up and down the river. Maj. Gen. Benjamin Butler’s Army of the James landed at Bermuda Hundred, about halfway between Trent’s Reach and City Point, where Grant established his logistics base. Union navy monitors, up to three or four at a time, operated with Butler’s troops and covered the army’s right flank as Butler moved toward Richmond. Mitchell, who took command of the squadron the day after Butler’s troops landed, moved its base of operations downriver to Chaffin’s Bluff, where the outer edge of the Richmond defensive line crossed the James. Inconclusive, long-range gun duels between the squadron and Union ironclads occurred in June, August, and October. That June, a line of 14 sunken hulks, chained together and reinforced by logs and nets, stretched across Trent’s Reach, blocking any movement downriver. Union warships were content to patrol behind the barricade and not challenge their Confederate counterparts. Although Butler’s army was stymied ashore, there were no serious threats to his presence from the James River Squadron during the last half of 1864.

But by January 1865, the Confederates were ready to act. They had learned that recent heavy flooding had washed away some of the obstructions at Trent’s Reach, creating at least a partial opening there. They also knew most of the Union monitors had been sent to the North Carolina coast to support the massive army-navy operation to capture Fort Fisher. The fort had surrendered on January 15, so the return of those ironclads to the James River was imminent. Navy secretary Stephen Mallory gave Mitchell his orders. “I regard an attack upon the enemy and the obstructions of the river at City Point, to cut off Grant’s supplies, as a movement of the first importance to the country,” Mallory wrote on January 16. Mitchell was slow to act, recalling his debacle with the Louisiana at New Orleans. Mitchell believed it wiser to defend the river “by heavy land batteries with the adjunct of torpedoes in every possible way,” while the ironclads should be “held in readiness.” Although not willing to act precipitously, Mitchell ordered a closer reconnaissance of the obstructions and readied his squadron to get underway to move downriver the evening of January 23.

Waiting for the Confederates on the eastern end of Trent’s Reach would be the Union navy’s North Atlantic Blockading Squadron, commanded by Admiral David Dixon Porter. Porter was overseeing the naval assault on Fort Fisher, so command of his Fifth Division on the James River fell on the shoulders of Commander William A. Parker. Parker, a native of New Hampshire, had served admirably on blockade duty, where he commanded the steam gunboat USS Cambridge and captured 11 blockade runners. Parker did not believe his small division of gunboats and one monitor was enough to stop the Confederate ironclads if they came down the James. He pleaded for more ships to be sent to him and advised the army to build up their batteries along the river. Parker was also aware some of the obstructions at Trent’s Reach had been washed away, but he didn’t believe he could replace them within range of the guns at Battery Dantzler, a mile away. “The rams will no doubt make a desperate attack on our vessels… if the water rises sufficiently to allow them to pass,” Parker wrote to Porter the evening of January 23, not knowing at that moment that Mitchell’s ironclads were already heading his way. Parker’s flagship was the USS Onondaga, the most powerful monitor afloat. Easily identified by her twin gun turrets, Onondaga was armed with two 15-inch Dahlgren smoothbores and two 150-pound Parrott rifled guns, the largest guns afloat (each two-gun turret mounted one 15-inches and one 150-pounder). Designed by George W. Quintard and launched from the Continental Iron Works on Long Island in July 1863, Onondaga carried 11 inches of armor on her turrets. It was completely made of iron, giving her hull greater strength than her predecessors. She was broader in the beam than the other monitors, making her a more stable and more formidable gun platform. One crewmember corresponded with a New York newspaper in 1864 and referred to the Onondaga as the “monarch of all she surveys.” At one point, the commanding general found time to visit the ironclad:

There had been so much talk about the formidable character of the double-turreted monitor that general Grant decided one morning to go up the James and pay a visit to the Onondaga... After looking the vessel over and admiring the perfection of her machinery, the general said to the commander: "Captain, what is the effective range of your 15-inch smooth bores?" "About eighteen hundred yards, with their present elevation,” was the reply. The general looked up the river and added: "There is a battery which is just about that distance from us. Suppose you take a shot at it and see what you can do." The gun was promptly brought into position by revolving the turret, accurate aim taken, and the order given to fire... The huge mass struck directly within the battery and exploded. A cloud of smoke arose, earth and splintered logs flew in every direction, and a number of the garrison sprang over the parapet. The general took another puff at the cigar he was smoking, nodded his head, and said, "Good shot!".

At 6:00 p.m. on January 23, Mitchell’s squadron got underway from Chaffin’s Bluff. Mitchell timed his departure to make the downriver transit in darkness and arrive at the high water obstructions. With the shallowest draft, CSS Fredericksburg led Richmond and Virginia II, Mitchell’s flagship. The wooden gunboats CSS Hampton, Beaufort, Torpedo, Nansemond, and the tender CSS Drewry were accompanying the ironclads. Also coming along were the small torpedo boats Hornet, Scorpion, and Wasp, each armed with an explosive charge. The smaller boats were lashed to the sides of the ironclads or towed behind. The group arrived under the guns of Fort Brady around 8:00 p.m. Alert sentries from the 1st Connecticut Heavy Artillery manning the guns spotted the vessels in the darkness. The fort opened fire as the Confederate flotilla skirted the turn below the bluff and continued south. Most of the Union gunfire was diverted by Confederate batteries across the river, providing cover for the ironclads who kept moving downriver. Things looked promising for Mitchell when his flotilla arrived at the western edge of the obstructions around 10:40 p.m. and found no Yankee warships waiting for them on the other side.

When the gunfire from Fort Brady alerted Parker that the Rebel ironclads were coming, he inexplicably withdrew his small force five miles downriver from Trent’s Reach to the army pontoon bridge at Deep Bottom. His request for more gunboats and monitors had gone unheeded, so Parker was forced to face the Confederate ships with what he had. Left behind with Onondaga were the wooden and lightly armed converted ferry USS Hunchback and the side-wheel gunboat USS Massasoit. Also available to Parker was the small torpedo boat USS Spuyten Duyvil armed with spar torpedoes. Outnumbered by three ironclads to one, Parker believed he could better maneuver his division in a wider stretch of the James near the bridge rather than challenge Mitchell’s flotilla at the barrier. “I thought my chances of capturing the whole fleet would be increased by allowing them to come down the river to the bridge, where I intended to attack them,” Parker said later. His decision nearly changed the outcome of the battle.

Back at the obstructions, Mitchell ordered the Fredericksburg and Scorpion forward to explore the barrier while the other ironclads waited in the darkness under the guns of Battery Dantzler. In charge of the two boats was Lieutenant Charles W. Read. Read had already served on the ironclad CSS Arkansas on the Mississippi and had famously captured 22 Union vessels with four different commerce raiders. Read, who was now commanding Mitchell’s torpedo boats, was responsible for clearing a passage for the ironclads through the gap in the obstructions before the river level dropped. Read and a few men, under fire from Yankee sharpshooters on the riverbanks, cut chains and sawed through spars, working quickly to widen the passage. By 1:30 a.m., Read reported to Mitchell that an 18-foot-deep channel was clear. Mitchell boarded the Fredericksburg and ordered her forward with the gunboat Hampton. Both vessels cleared the obstructions and anchored near Dutch Gap about a mile downriver on the Union side.

Mitchell returned to the Richmond and Virginia II and, to his “inexpressible mortification,” found them both aground as the river level had dropped several feet. Mitchell now faced a critical decision. He could continue downriver with the Fredericksburg and Hampton, with no idea what Union vessels awaited him. Or he could hold on where he was and try again later with his entire command. With dawn coming, his flotilla would soon be at the mercy of the Union batteries on the east edge of Trent’s Reach. Reluctantly, as daylight broke over the river, Mitchell ordered the Fredericksburg and Hampton back to Battery Dantzler to await the late morning high tide. “The Fredericksburg was now recalled and ordered to take up a position above the Richmond to cover, if practicable, the grounded vessels with her broadside,” he reported later. Mitchell did not realize it yet, but the “high water mark” of the James River Squadron had passed.

Around 1:00 a.m., Grant was awakened at City Point and was told the obstructions had been breached and that Parker’s division had withdrawn downriver. Grant was incensed because his base at City Point was now in grave danger. “He seems hopeless,” Grant telegraphed navy secretary Gideon Welles, requesting that Parker be relieved. “It is an inexpressible mortification to think that the captain of so formidable an ironclad… should fall back at such a critical moment,” Grant told his staff. In an unprecedented move, Grant communicated directly with each of the squadron’s commanding officers, ordering them back upriver to meet the Confederate ironclads: “This order is imperative, the orders of any naval commanders to the contrary notwithstanding,” he wrote to them. Grant then wired the navy department, “I have been compelled to take the matter into my own hands.” He received no objection from Welles.

By the time the torpedo boat Spuyten Duyvil returned to Trent’s Reach, the Fredericksburg and Hampton had retreated. As the other Union warships worked their way back upriver, daylight revealed to the 1st Connecticut Heavy Artillery gunners the Confederate flotilla stranded in the river below. The shore batteries erupted with a barrage of fire upon the hapless ironclads and gunboats. During what Lieutenant Read called a “perfect rain of missiles,” a 100-pound shell struck the tender Drewry, blowing her up and disabling Read’s torpedo boat Scorpion. Most of the projectiles fired from the batteries found their mark, riddling Virginia II’s smokestack and upper decks while wounding several men. Rifle fire from the riverbanks added to the carnage. The pounding continued into the late-morning hours when, to Mitchell’s relief, the incoming tide began to lift his vessels off the bottom one by one.

Then the Onondaga returned, followed by the Hunchback and Massasoit. The twin-turreted monitor opened fire on the Confederate ironclads around 10:45 a.m. from less than a mile away. Her 15-inch and 100-pound rifles blasted away at the Virginia II and Richmond, the two vessels closest to her. “Hit the rebel rams several times,” the monitor’s log recorded, and a crewmember reported her solid shot flew “thick and heavy.” One shell from Onondaga tore through Virginia II’s 4-inches of armor plate and crushed the two-foot-thick wood underneath, “jarring her from stem to stern,” according to her captain, and “breaking the iron and crushing the woodwork completely in, making a large hole through.” One man was killed, and two were wounded. Richmond’s gun shutters and anchors were blown away. Her captain found that she was hit “three times with heavy shot, causing decided shocks and knocking off the heads of bolts.” Both sides blasted away at each other, the deafening fire from the big guns echoing off the riverbanks. As the hammering continued, Richmond’s captain reported that his ironclad was “struck so constantly by shot and shell that it was impossible to keep account of the number,” but her sides were not penetrated. On Virginia II, her captain reported that “I am of the opinion that the two most damaging shots, one aft on the port side of [the] shield, and one between [the] after port and port quarter port, were fired from the monitor.” Fredericksburg was not damaged by Onondaga, but she had developed a leak from her dash through the obstructions and was taking on water. Mitchell’s casualties were light: five were killed and 17 others wounded, most of them on the Virginia II, which had been struck by over 70 shells from Onondaga and the shore batteries. Mitchell decided to cut his losses and move his battered warships out of range. As the morning tide rose and the Confederate squadron floated free, he ordered a retreat upriver above Battery Dantzler.

But the battle was not over yet; Mitchell was determined to try again. Although heavily damaged, his ironclads were still functional. His crews took most of the day on January 24 to make what repairs they could and moved their wounded to safety. By around 9:00 p.m., Mitchell was ready to return downriver. Once underway in the darkness, the pilot on the Virginia II found it difficult to maneuver the ironclad, which leaked steam inside the casemate. Fredericksburg’s pumps worked furiously as she continued to take on two to three inches of water every hour. As the flotilla rounded Trent’s Reach, the Union gunners were waiting. During the day, along the south riverbank, they had installed a Drummond light: an intensely bright light that burned lime ignited by a hydrogen flame. The light came on as the Confederate ironclads neared the line of obstructions, and gunfire from the shore batteries erupted anew. Virginia II’s captain found that the brightness “illuminated the area, allowing the batteries to fire nearly as accurately at night as they had during the day.” Unsure of whether to continue, Mitchell called his ship captains together. Lieutenant Read, the most junior officer present, pleaded for a chance to pass through the obstructions again in daylight and attack the Onondaga with his torpedo boats. Mitchell disapproved of Read’s request and again reluctantly decided to withdraw his fleet, this time all the way back to Chaffin’s Bluff. Once again, the gunners at Fort Brady were waiting and rained still more shot and shells down on the retreating ironclads. By sunrise on January 25, the gunfight at Trent’s Reach was over, Grant’s supply base at City Point was secure, and the last chance of the Confederate Navy to break the siege of Richmond and Petersburg was gone.

Parker’s Fifth Division was barely hit during the battle. Onondaga had no casualties but was slightly damaged: her boats were shot to pieces, and one 7-inch round pierced her smokestack. However, Commander Parker’s naval officer career was irreparably wrecked. Welles acted on Grant’s request and relieved Parker of his command while the battle at Trent’s Reach was still in progress. Belatedly, the big ironclads USS New Ironsides and USS Atlanta were ordered up the James from Hampton Roads but did not arrive in time. The morning after the battle, Parker turned over his command to his senior subordinate. Two days later, Parker appealed his removal in writing to Grant and Welles, outlining his attempts to seek reinforcements. “I pray that you will order an investigation of the facts," he asked. In March, Parker was given a court martial where he was found guilty of “willful cowardice” by moving the Onondaga downriver “for the discreditable purpose of avoiding an encounter with [enemy] vessels.” By that time, the heat of the battle had cooled, and Welles had softened his charges, telling the board members reviewing Parker’s case that he believed the commander’s decision was an “error in judgment” rather than for a “discreditable purpose.” Parker’s sentence to be dismissed from the Navy was vacated, and instead, his name was moved to the retired list.

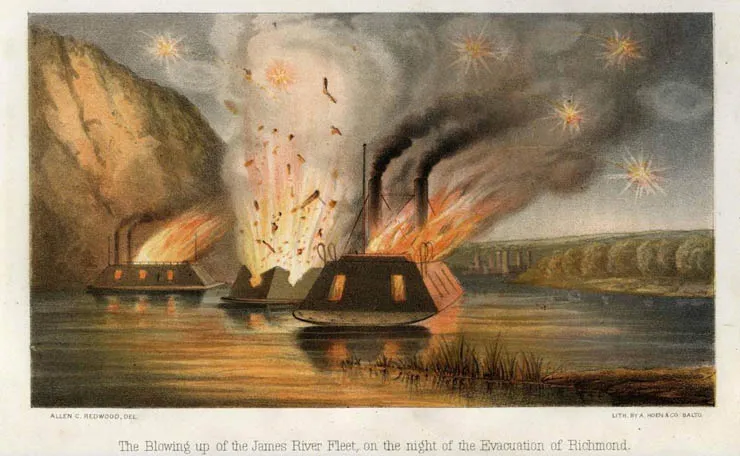

Mitchell fared a little better, although no charges were filed against him. He believed firmly that his entire squadron could have passed through the obstructions if Virginia II and Richmond had not grounded. “As the result has proved so unfortunate… I invite the closest scrutiny into the manner of conducting the enterprise committed to me,” Mitchell concluded in his official report. He was relieved of his command of the James River Squadron in mid-February by Admiral Raphael Semmes, another highly acclaimed veteran of Confederate commerce raiding and former captain of the CSS Alabama. Semmes oversaw the ironclads' repairs but made no further attempts to move them downriver. The obstructions at Trent’s Reach had been strengthened, and more Union warships patrolled the lower James. On April 2, with the fall of Richmond inevitable, Semmes was ordered to destroy his ironclads and send his sailors to join Robert E. Lee’s retreating army. Richmond, Virginia II, and Fredericksburg were blown up and sunk near their base at Chaffin’s Bluff, where they lie today under the silt of the river they once fought to defend.

Related Battles

3,500

4,250