At the outset of the Civil War in April of 1861, the Abraham Lincoln administration faced military challenges ashore and afloat. The regular U. S. Army, mustering around 16,000 men, was not large enough and was too spread out across the states and territories to mount a campaign against Richmond. On April 15, two days after the fall of Fort Sumter, Lincoln called for 75,000 new soldiers to suppress the rebelling states. Similarly, the U. S. Navy that April could count only 42 commissioned warships, spread from Boston to Pensacola, and stationed overseas. Navy Secretary Gideon Welles ordered a crash shipbuilding and acquisition program, and on May 3, Lincoln issued a call for 18,000 new sailors to take the war to sea.

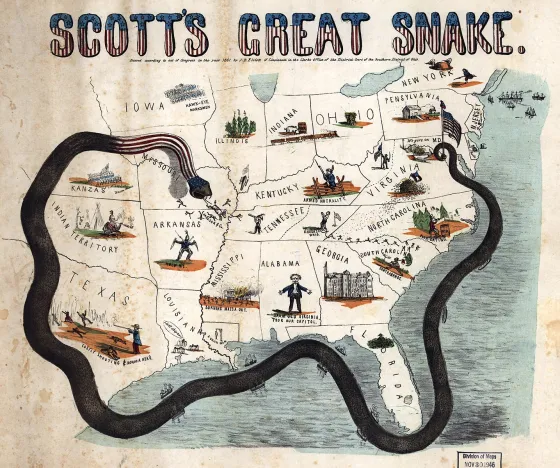

By mid-1861, the Navy had four missions. First, warships were needed to support the new blockade of Southern ports. Union war plans included crippling the Confederacy’s economy by strangling their export of cotton, tobacco, and other cash crops. Second, shallow-draft vessels were needed on the inland rivers, particularly the Mississippi and its tributaries, to support army operations. Third, Union warships were tasked with destroying Confederate commerce raiders on the high seas. And fourth, Union squadrons were charged with closing port cities and reducing coastal defenses. At one time or another during the war, all of these operations were conducted along the coast of the Gulf of Mexico.

The geography of the operations area was daunting. The Gulf of Mexico reached from Cuba to Mexico. The Confederate coastline stretched 1,700 miles from Key West to the Rio Grande. For much of that distance, barrier islands provided inlets and coves and hundreds of small ports to protect blockade runners. Big rivers like the Mississippi, the Sabine, and the Chattahoochee accessed the Confederate interior. The largest city in the Confederacy, New Orleans, was just 70 miles upstream from the Gulf coast, and the fourth largest city in the south, Mobile, was 30 miles inside Mobile Bay. Organizationally, the Union West Gulf Blockading Squadron covered the coastline from the Mississippi River to Mexico, while the East Gulf Squadron covered the remainder.

The war began early on the Gulf coast. On January 10, 1861, the day Florida seceded from the Union, the U. S. army’s garrison at Pensacola moved to the protection of Fort Pickens in the outer harbor, surrendering the navy shipyard there to the Rebels. Recognizing the importance of Pensacola as a coaling station and ship repair facility, the Union navy placed blockading vessels outside the harbor and made plans to recapture the base. On the night of September 13, 1861, a Union raiding party from the USS Colorado quietly entered the harbor in the darkness. There, they burned the Confederate privateer CSS Judah at the shipyard. The Confederate defenses were bombarded on November 22 and 23 by the USS Niagara and USS Richmond, heavily damaging the Rebel guns. In May 1862, Confederate soldiers were needed elsewhere and the base was abandoned. The Union navy occupied the shipyard, and it proved useful to Yankee blockaders for the rest of the war.

By April 1862, with a Union army moving south towards Vicksburg, the Union navy turned its attention to capturing the lower Mississippi River. A small naval battle had taken place on October 12, 1861, at the Head-of-the-Passes, where the big river empties into the gulf. There, a small, improvised “mosquito fleet” of Confederate gunboats, fire rafts, and the new ironclad CSS Manassas took on five larger Union ships and chased them out of the river delta. Despite the embarrassing setback, by mid-April, 1862, Union Admiral David G. Farragut had readied a large fleet of 43 warships to capture New Orleans. On April 24, after a 6-day long mortar bombardment, Farragut led his fleet past Forts Jackson and St. Phillip guarding the river below the city. Under the guns of the forts, Farragut’s big ships battled with the ironclads Manassas and the new CSS Louisiana, neither of which could impede the progress of the Union warships. Both ironclads were sunk during the battle or soon thereafter. New Orleans surrendered to Farragut on April 29, and the largest city in the Confederacy was in Union hands.

The gulf coast of Texas saw its share of naval action during the war. The Confederates hoped to establish trade between Texas and Mexico to obtain much-needed resources and supplies. In early August 1862, the West Gulf Squadron established the blockade at Corpus Christi with five small vessels. A battle ensued on the 12th when the ships encountered four Confederate schooners and a steamer protecting the harbor and nearby Fort Kinney. One of the Confederate ships was captured; the others were scuttled. With the defenses of the port weakened, the Union commander landed a force of sailors to demand the surrender of the fort. When the Confederates refused, the fort was silenced by gunfire from the ships. Although Fort Kinney held out they could not control the port, effectively closing Corpus Christi to blockade runners.

The Union attempt to cut Texas off from the Confederacy by sea and land shifted north to Galveston and the nearby mouth of the Sabine River. Blockade runners used both ports and a nearby railroad connected them to the east. On September 24, 1862, a Union steamer and two schooners opened fire on the defenders of Fort Sabine, four miles up the river at Sabine Pass. The small garrison had poor artillery and could not effectively return fire on the Union vessels at long range, so the commander ordered the guns spiked and evacuated his men that night. Union navy officers occupied the fort and received the surrender of the town the next day. Later, the Yankees received faulty intelligence that a Confederate army was gathering nearby, so the town and fort were evacuated and left to the Rebels.

At Galveston, another small Union navy flotilla of four steamers and a mortar boat, led by the former revenue cutter USS Harriet Lane, attempted to enforce the blockade there. Entering the harbor on October 4, 1862, the Yankees demanded the surrender of the city. A handful of Confederate infantry defenders refused. After an ineffectual exchange of artillery fire with Fort Point, both commanders negotiated a turnover of the city, closing another port to the rebels. Three months later, however, on the first day of 1863, the Confederates returned with two cottonclads and some infantry under the command of Maj. Gen. John B. Magruder. Magruder’s two ships attacked six Union vessels now stationed there, losing one cottonclad and capturing the Harriet Lane while grounding another Union gunboat on a sand bar. The Union commander was killed attempting to scuttle one of his vessels, and his remaining men and ships retreated to New Orleans. Galveston finally surrendered in June 1865; the only major port that remained in Confederate hands at the end of the war.

Later in 1863, the West Gulf Squadron returned to Sabine Pass. Union commanders were convinced that an infantry force sent to Beaumont, 30 miles inland, would cut the railroad between Texas and the rest of the Confederacy. On the morning of September 8, a Union flotilla of four gunboats and seven infantry transports steamed into Sabine Pass to reduce the defenses and land troops. This time, as the gunboats approached Fort Griffin (the same fort evacuated by the Yankees a year earlier), they came under accurate fire from gunners who held their fire until the vessels were within point-blank range. The fort’s small force of 44 men disabled two Union ships and captured a gunboat with about 200 prisoners, forcing the flotilla to retire. The Confederate defenders suffered zero casualties and Union expeditionary operations in the area finally ceased.

Meanwhile, the East Gulf Squadron was busy along the Florida coast. The steam schooner USS Sagamore, with five guns, spent much of the war capturing ports and blockade runners. On April 3, 1862, Sagamore and the USS Mercedita captured the town of Apalachicola without resistance. Taking the town was an important victory: 140 miles upriver was the Columbus Naval Iron Works, where two new ironclads were now trapped in the Chattahoochee River. On June 30, Sagamore attacked Tampa and exchanged fire with a Confederate artillery battery there, later withdrawing without capturing the port. On September 11, she destroyed the salt works at St. Andrews Bay. Between December, 1862 and the end of April, 1863, Sagamore captured or destroyed six blockade-running vessels. On July 28, 1863, she shelled the town New Smyrna, destroying two schooners and a large store of cotton, and in August she captured four more blockade runners. In April, 1864, Sagamore and another ship operated in the Suwannee River, where they destroyed over 500 bales of cotton. The squadron returned to Tampa on October 16, 1863, when two vessels bombarded Fort Brooke and landed a party that destroyed two blockade runners at a shipyard before being chased back to their ships.

The war was fought in the deep waters of the Gulf of Mexico also, not just along the coast. On June 3, 1861, the new commerce raider CSS Sumter, under the command of Captain Raphael Semmes, broke through the Union blockade of the Mississippi River. Sumter had been converted from a commercial 3-masted steam bark and was now armed with four 32-pound guns. Sumter captured eight Yankee merchantmen around Cuba before moving into the Atlantic. On January 11, 1863, the raider CSS Alabama, Semmes’s next command with 28 captured Yankee merchant ships from the Atlantic and Caribbean listed in her deck log, met her first military opponent off the Texas coast. There, she found the USS Hatteras, a side-wheel steam gunboat with 20 captured or destroyed blockade runners to her credit. The 5-gun Hatteras dueled with the 6-gun Alabama for 20 minutes at close range just after dusk, but the Union ship was no match for the big 32-pounders on the raider. Hatteras went down in 45 minutes. The commerce raider CSS Florida also operated briefly from Mobile Bay and around Cuba in late 1862, before taking 37 Yankee ships in the Atlantic as prizes.

The largest naval action in the gulf, and one of the biggest of the entire war, took place in the summer of 1864. By then, the Union was ready to close Mobile, Alabama, to blockade running traffic for good. The effort was put under the command of Farragut, who had successfully run past the forts and ironclads at New Orleans and Vicksburg in 1862. Farragut led a land and sea operation that began August 3 to reduce Forts Gaines and Morgan guarding Mobile Bay. Farragut successfully entered the bay on August 5 with 18 big, wooden warships and four ironclad monitors and captured the Confederate fleet defending the port, including the ironclad CSS Tennessee. Cut off, the forts surrendered by August 23. Without the protection of the forts, the bay could no longer harbor blockade-running vessels. The city of Mobile fell to a Union army expedition eight months later, three days after Robert E. Lee’s surrender at Appomattox.

The war raged along the Gulf of Mexico coast from Florida to Texas and up Confederate held rivers. The East and West Gulf Squadrons did their share to contribute to Union victory. Union warships seemed to be everywhere, all the time, capturing Confederate ports and stopping blockade runners. Confederates scored some victories too; especially with their big, fast commerce raiders. In the end, however, as with the armies, the numbers were with the Yankees. The Confederate Navy could not sustain a prolonged, offensive presence in the Gulf to make a difference in the outcome of the war.

Further Reading

- War on the Waters: The Union and Confederate Navies, 1861-1865 By: James M. McPherson

- Iron Dawn: The Monitor, the Merrimack and the Civil War Sea Battle that Changed History By: Richard Snow

- Lincoln and His Admirals By: Craig Symonds

- The Civil War at Sea By: Craig Symonds

Related Battles

322

1,500