The USS Tecumseh strikes a mine and sinks

Looking north from the beach at Mobile Point, Alabama, a handful of oil platforms clutter the inside of Mobile Bay, a few miles offshore. To the south, seaward, the Gulf of Mexico fills the horizon, and fishing boats work back and forth, harassed by seagulls. Close by to the west, cruise ships and container vessels use the ship channel to enter and exit the bay, still guarded by the brick ramparts of Fort Morgan. And some 100 yards off the beach, just inside the channel, a lonely steel buoy bobbing in the waves marks the final resting place of the U. S. Navy warship USS Tecumseh and 94 of her crew.

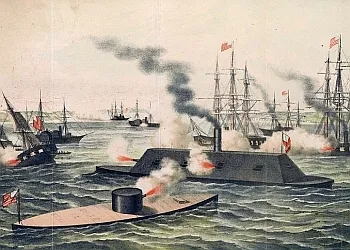

In the summer of 1862, the Union Navy was gripped with “Monitor Fever” after the better-than-expected performance of the revolutionary new warship USS Monitor in her battle against the CSS Virginia on March 9. The battle was a tactical draw, but the undersized and outgunned Monitor neutralized the Virginia and kept Hampton Roads in Union control. John Ericsson, the designer of the vessel, took note of his ironclad’s combat performance against Virginia and made improvements to the next class of monitors. Named for the lead ship USS Passaic, the next six vessels made incremental improvements in maneuverability, firepower, and command and control over Ericsson’s original design. Before any ironclads of the Passaic class could see any fighting, Union navy secretary Gideon Welles ordered nine more monitors to be built. Named for the lead ship USS Canonicus, this new batch of ironclads were a further improvement over their predecessors, and several modifications were made during their construction based on the combat experiences of the Passaic class in Charleston Harbor in April 1863. Named for Indian tribes, landmarks, or tribal leaders, contracts for $460,000 each were signed in September and October 1862, and the new vessels were laid down in six different commercial shipyards on the Ohio River and along the Atlantic coast. In addition to the Canonicus, the vessels were named USS Catawba, Mahopac, Manayunk, Manhattan, Oneota, Saugus, Tippecanoe, and Tecumseh.

Construction on the Tecumseh began on October 8, 1862, at the Charles A. Secor and Company Shipyard on the Hudson River in Jersey City, New Jersey. Tecumseh was 225 feet long overall, 43 feet across her beam, and had a draft of 13 feet. She displaced 2,100 tons, more than twice the volume of the Monitor. Although a larger and more stable seagoing vessel than the Monitor and the Passaic class, the Tecumseh drew only one foot more water, allowing her to operate in shallow water in rivers or near-shore like the other monitors. Her hull was framed by wrought iron beams, and her deck was built with one-and-one-half-inch white pine planking, supported by 12-inch by 16-inch oak beams and covered with one-and-one-half inches of armor. Like the Passaic class, the sides of Tecumseh’s hull were sheathed with five inches of armor plate, but the new ship also carried four-inch thick iron stringers inside along her hull. Her main deck was sloped downward 5 inches on each side to drain seawater, an improvement in seakeeping over the Monitor.

Tecumseh was powered by two vibrating-lever type, 640-horse power steam engines of Ericsson’s design, fed by steam from two primary and two auxiliary boilers. Two coal bunkers with a capacity of 150 tons provided fuel for the boiler furnaces. A massive, armored telescoping funnel on deck carried away exhaust smoke from the boiler rooms, and a 25-foot ventilator stack provided exhaust for the ship’s galley and other machinery. Three wooden lifeboats were carried in davits or lashed to the main deck. Two high-capacity blowers brought outside air from above the turret down through the fire room, officer’s quarters, and the crew’s berthing deck. Mounted forward of a single rudder on a 15-inch diameter shaft, the engines drove a cast iron, four-bladed, 14-foot propeller designed to move the Tecumseh through the water at 13 knots (about 15 miles per hour).3

Like her predecessors, Tecumseh was designed with a single, rotating turret with two 15-inch guns. For Tecumseh and the rest of the Canonicus class, two 15-inch guns were available for each vessel, making them the most powerful monitors built. Each 15-inch gun was mounted on a specially designed carriage weighing 45,000 pounds and required a crew of eight men to load and fire. Each gun required five minutes to reload. Using a 35-pound charge of gunpowder, a 350-pound shell or 440-pound solid shot could be fired 2,100 yards or just over one mile. Increasing the powder charge to 50 pounds gained an extra 300 yards of range at a maximum elevation of seven degrees. At point-blank range, the effects of the guns were devastating.

In a significant design change, Tecumseh’s turret was mounted 20 feet further forward on the hull, much closer to the bow than her predecessors. The turret, one foot wider in diameter than Monitor’s, was armored with ten, one-inch thick curved armor plates. Tecumseh and her sisters also incorporated a ring of armor five inches thick and 15 inches high around the base of the turret to prevent it from being jammed by shot. In another design change from the Passaic class, the pilot house was moved from the bow to the roof of the turret and was covered with ten inches of armor. This modification removed the pilot house as an obstacle to the guns as they fired forward and provided better steering visibility. A steel plate three feet high and a half-inch thick was mounted around the top of the turret to protect the pilot house from rifle fire from ashore or other ships. Tecumseh’s brass magnetic compass, subjected to errors from the abundance of surrounding steel, was moved from inside the pilot house to the top of a mast-mounted 7 feet above it; the ship’s helmsman observed his heading through a periscope inside the length of the mast. Watertight hatches on the main deck forward, amidships, and aft led down into the ironclad’s interior. Access to the pilot house was gained through a single hatch and ladder inside the turret; another ladder and hatch led outside through the turret top.

Tecumseh was finally launched on September 12, 1863, one year after her construction contract was signed. Launch day was a big event and was covered by the local newspapers:

The number of spectators present was somewhat over five thousand. The yard, housetops, windows, adjoining piers, and every available place thronged with people, while the vessel's deck was crowded with invited guests. It shows interest our people take in the progress of the ironclads to see so many of them abroad at such an early hour to witness the launch of a vessel.. . At half past seven o'clock, the workmen commenced to wedge her up, and at eight o'clock she began to move slowly down the ways towards her native element. As she moved from the stocks, Mrs. Kate Gregory, daughter-in-law of Admiral Gregory, in a most pleasing manner, amid the cheers of the multitude, christened the vessel by breaking a bottle of wine over the bow with the words "In the name of Neptune, I christen you Tecumseh."

Tecumseh’s 15-inch guns were mounted on January 6, 1864, and her machinery was installed and tested on January 28. Sea trials in New York Harbor were completed on March 28 with “a number of prominent naval officers” in attendance. Before the final delivery to the navy, the ship was hauled out of the river to have her bottom scraped and painted. After all modifications, the total paid for the ship was $701,624, more than 50 percent over the contract price. USS Tecumseh was finally commissioned as a U. S. Navy warship on April 19, 1864.

The guns and steel of a warship are not brought to life until a crew is assigned. Command of Tecumseh was given to Commander Tunis Augustus Craven in March 1863, six months before her launch. Craven was born on January 11, 1813, at Portsmouth Naval Yard in New Hampshire, where his father served as the shipyard storekeeper. Craven had entered the navy at age 16 as a midshipman and served on coastal survey duty as a young officer. During the Mexican War, Craven served on the sloop-of-war USS Dale on the western coast of Mexico. In October 1847, Lieutenant Craven led a detachment of sailors and marines from the Dale ashore in an inconclusive skirmish with Mexican militia. When the Civil War broke out, Craven was given command of the new steam sloop-of-war USS Tuscarora and took her to sea in search of Confederate commerce raiders. Under Craven’s command, Tuscarora pursued the CSS Sumter into port at Gibraltar, where the raider was prevented from leaving and was ultimately abandoned. Craven requested command of an ironclad when Tuscarora returned to New York in March 1863, and he was given command of Tecumseh that month. For another year, Craven supervised the fitting out of his new ship, and he became intimately familiar with the vessel and how she performed underway.

Lieutenant John W. Kelley, the ship’s Executive Officer, was born in Ireland and emigrated to America in 1849. He graduated from the Naval Academy in 1857 and served on the sailing frigate USS Sabine until 1862. When Sabine was decommissioned, Kelley requested duty onboard an ironclad and received orders to the Tecumseh. Kelley, responsible for maintaining discipline among Tecumseh’s crew, had served under then-Captain David G. Farragut as a young officer. Commander John Faron from New Jersey was the engineering superintendent of the monitors under construction at the Secor shipyard. He was slated to take an engineering assignment on a new monitor just laid down in early 1863, but instead requested orders to an ironclad ready to go to sea, so he was named Tecumseh’s Chief Engineer. Faron was in the Pensacola naval hospital, severely weakened by cystitis, just before Tecumseh departed for Mobile Bay. When he learned he would be replaced on the ironclad, he dragged himself out of his hospital bed to rejoin the ship. Tecumseh’s paymaster was a 42-year-old Connecticut bachelor schoolteacher and trader named George Work. Work had never been a sailor but joined the navy anyway in 1862. Assigned briefly to the naval school at the Brooklyn Navy Yard, Work received his orders to Tecumseh in February 1864. Work found duty aboard the ironclad difficult in the summer heat, and his health deteriorated, but he hesitated to ask for a reassignment. Work stuck to his duties and remained on the ship for the time being. Acting Ensign Walter L. Titcomb from Maine was assigned to the gunboat USS Owasco in August 1864 and had been an officer for less than a year. When Owasco was laid up for long-term repairs at the navy base in Pensacola, Titcomb wrote a letter home to his father, a civilian mariner:

"[Admiral] Farragut is about to attack Mobile: he has not men enough now, and there will be hot work before he gets in. As 'The Owasco' is at the Navy Yard for repairs and will be unfit for duty until October, I have offered my services for the impending fight and asked to be transferred temporarily to some vessel that will take an active part in the engagement. I came out here to fight for the cause, and I wish now to do all in my power to advance it;…. Have I done right, father?"

Titcomb and 11 other crewmembers of the Owasco were transferred to the Tecumseh just before she departed Pensacola for Mobile Bay. A total of 145 sailors served under Craven and Kelley on the Tecumseh throughout her short career. Most of them reported aboard Tecumseh in New York shortly after her commissioning. Like the officers, most of the men had served on other ships, and they came from homes up and down the East Coast and the Great Lakes. Reflecting on the country they served, Tecumseh’s crew represented many nationalities: 52 were from the British Isles, four were from Canada, two from Germany, and one each from Portugal, Peru, Aruba, and France. At least one was an African-American.

Tecumseh’s crew of 81 officers and sailors had little time to train together. In May 1864, just two weeks after her commissioning, Ulysses S. Grant initiated coordinated offensive operations by Union armies across the Confederacy. In Virginia, Benjamin Butler’s Army of the James was charged with moving against Pierre G. T. Beauregard’s forces defending Richmond. Supporting the operation as escorts for Butler’s troopships, Tecumseh and her sisters Canonicus and Saugus, joined by the new double-turreted monitor USS Onondaga, were attached to the North Atlantic Blockading Squadron, commanded by Rear Admiral Samuel P. Lee, Craven commanded the flotilla of monitors as the senior officer.

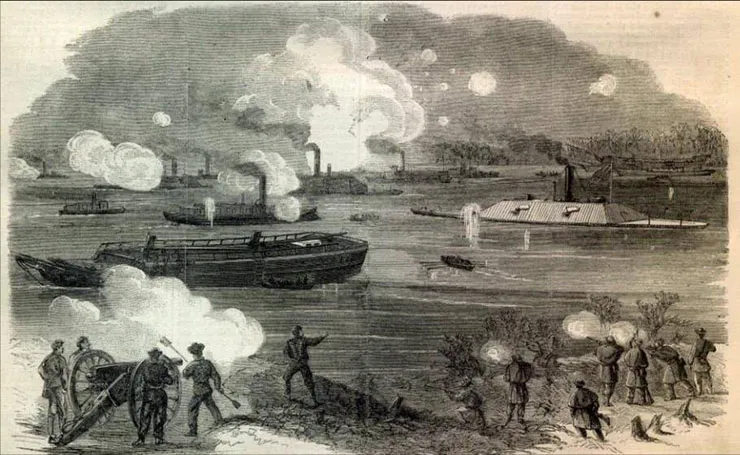

The first week of May, as Butler’s army landed at Bermuda Hundred, Tecumseh, and the other monitors slowly moved up the James, guarding the infantry’s flank. “The passage up the river was attended with great difficulty, as the enemy had sunk torpedoes in the channel, making it an extremely hazardous undertaking,” remembered Seaman Frank Cousins. There were other dangers too. Ordinary seaman Peter Holland was topside working on the main deck the morning of May 6. As Tecumseh navigated a bend in the river, Holland was shot in the face by someone from the river bank. He stumbled down a hatch into the chain locker. The ship’s surgeon, Dr. Henry Danker, treated Holland and remained aboard with injuries to his face, shoulder, and hip.

Confederate naval mines (known then as “torpedoes”) were a constant threat. Rear Admiral Lee reported the flotilla encountered several and that the ships were “fishing out torpedoes as we go.” Many elected officials and general officers on both sides considered the irregular warfare devices as “infernal machines” and were reluctant to sanction their use. Recognizing, however, that the relatively inexpensive devices could make up for a shortage of ironclads and heavy artillery, the Confederate congress in October 1862 had authorized the creation of a Torpedo Bureau within the Navy Department. Most of the devices developed were cylindrical or cone-shaped oak or tin barrels filled with 50 to 100 pounds of gunpowder. A contact plate or percussion cap struck by a passing ship would ignite a firing pin, detonating the powder charge. Most were anchored to the bottom with a tether that held the device just below the surface. On May 6, the Union transport ship USS Commodore Jones was destroyed by a torpedo on the James detonated remotely from ashore, taking 40 soldiers with her. Fearful of losing a monitor, the advance of Craven’s flotilla up the river was slowed by Lee’s orders to sweep the river for torpedoes as they went.

By the end of May, Butler’s forward line stretched from Trent’s Reach on the James River to the Appomattox River three miles south. With Grant’s concurrence, Butler and Lee agreed to block the James at Trent’s Reach to prevent Confederate warships, including the ironclad rams CSS Virginia II, Richmond, and Fredericksburg, from descending the river and threatening Butler’s infantry. On May 28, navy secretary Welles ordered Tecumseh to leave the James and proceed to sea with orders transferring the ironclad to Admiral David G. Farragut’s growing fleet at Pensacola, preparing for an assault on Mobile Bay. Lee communicated with Welles and begged to have Tecumseh remain on the James. Lee believed it “imprudent” to give up Tecumseh as he believed his river flotilla was threatened with an “immediate attack” from Confederate “fire rafts, torpedo vessels, gunboats, and ironclads.” Welles countered that Lee “had the best ironclads in the Navy, and Admiral Farragut, threatened by a larger force than is opposed to you, has not a single one.” Lee agreed that the monitors assigned to him were “better than was originally expected” but reminded Welles that Grant had expected the ironclads to secure the river covering the army’s flank. Lee believed that it would “be of vital importance to the success of the campaign that the river should be held securely against the casualties of a naval engagement.” Welles acquiesced and endorsed Lee’s request to keep Tecumseh for the time being.

From June 15-18, crewmen from Tecumseh and the other monitors sank four hulks and a schooner in the river at Trent’s Reach and stretched a heavy chain between them from the north bank to the south. On June 19, Craven’s flotilla engaged in some improvised target practice with unintended results. Craven’s ironclads opened fire upriver over the treetops and across the river bends. A Confederate officer from the gunboat CSS Richmond anchored upriver and reported what happened:

On the 19th of June, our squadron got underweigh from the anchorage at Chapin’s Bluff and proceeded down the river. At 2 p.m., we anchored off upper Howlets [Farm], which I suppose is in an airline two miles from [Trent’s Reach], but by the river much farther. Butler had erected a tower of wood at Trent’s Reach, perhaps 120 feet high, as a post of observation. It gave him a very good one… From our anchorage, nothing could be seen of the monitors in Trent’s Reach—in fact, we were anchored under a bluff on the right bank of the river… We had been at anchor an hour or two, not expecting a movement of any kind—indeed, I was sitting in an armchair on the shield of the Richmond reading—when a shell was fired from one of the monitors in our direction. It exploded just at the river bank and scattered the pieces about the forward deck of the Virginia, wounding three men. Whilst we were wondering at this, another shell came and exploded just after it had passed over us, and again another. As we could not return the fire, and there was no necessity to remain and be made a target of, we got underweigh and went back to Chapin’s Bluff. As the guns had to be pointed by directions from those in the tower I have mentioned, I thought this the most remarkable shooting I had ever seen or heard of but happening to mention this circumstance after the war to a naval officer present at the time on board one of the monitors, he informed me that they were not shooting at us at all. He said that some officials had come from Washington on a visit, and they wishing to see a large gun fired, the monitors had obliged them.

The Confederate ironclads wisely remained out of range of the monitors on the James for the remainder of the year. Tecumseh’s combat on the James continued two days later with more substantial effects. Early on June 21, from behind the barricade across Trent’s Reach, Craven observed a rebel artillery position that had been concealed with brush:

At 10:30 a.m., observing a gang busily occupied on the right of this new battery, I threw into it five XV-inch shells, two of which exploded in the right place, destroying a platform, throwing the plank and timber in every direction. At 11:30, the enemy commenced moving the brush and unmasked a battery of six embrasures, in four of which guns were mounted. I immediately renewed my fire on the battery and ordered the Canonicus and Saugus also to open. The enemy opened his fire upon us at [noon] with four guns, two of them heavy caliber… Our fire was delivered slowly and with great precision, most of our shells exploding within the works of the enemy. At 1:30 p. m. I ceased firing and gave my crew a half hour to rest and eat their dinner. At 2 recommenced and continued firing slowly until 4 p. m., our last shell silencing one gun, the shell having traversed through the embrasure and disabled it. The estimated distance was 2,000 yards. This ship expended forty-six XV-inch shells and was not hit.

Paymaster Steward Thomas Brown on Tecumseh recalled the effect of the Confederate artillery fire on the monitor flotilla:

"It was fun to be on deck and hear the steel pointed shot came singing along like a locust, and the minute we would hear them, we would all run behind the turret and hearing it up close and see the shot and shell go singing over our heads and drop in the water just astern of us. The monitor named Canonicus from Philadelphia laid close alongside of us so you could jump from one to the other. She was more unfortunate than us, one shot went through the top of her smoke stack and made three holes, and another one came along and struck her deck and made a dent about 4 inches deep and jumped up and tore her awning and skipped overboard. The Boston monitor called Saugus, just a little to our left got struck on the front of her turret with a rifle ball and it made a large dent and bounced clear back about 20 feet and fell overboard. That is the only damage that is being done yet. I think the Rebs are sick of us, for we put the shot and shell in there at a fearful rate, we knock[ed] their battery most all to pieces dismounting three of their guns."

Craven and the Tecumseh crew would not have long to wait to apply their experience of dodging torpedoes and firing at Confederate defenses.

On June 23, Welles ordered Lee to send Craven and the Tecumseh to Hampton Roads “as soon as practicable.” Lee gave Craven sealed orders to be opened only upon his arrival in Norfolk and wished Craven “a pleasant passage and regretting very sincerely to part with you and your efficient command.” Steward Thomas Brown and most of the crew knew where they were headed. “We have weighed anchor and are now on our way down the river, so I will let the letter stop until we get to our destination, I think we are bound for Norfolk,” Brown wrote home to his family.

Tecumseh anchored in Hampton Roads on June 25. Craven opened his orders sending Tecumseh to Pensacola to rendezvous with the rest of Farragut’s fleet gathering for the attack on Mobile Bay. That night, Steward Thomas Brown closed his letter home and gave his family an insight into life on a monitor headed for certain combat:

"While I write, the perspiration is running off me like water. A good many of our men are sick with the diarrhea and I have it quite bad myself. The report is we are bound for Mobile... The distance to Mobile is about 1500 miles right at sea all the time we will be batten[ed] down about 10 days… I will write to you as soon as we reach our destination if ever we do, which I am sorry to say is doubtful, for it is the first monitor that has dared to my knowledge, to endure so far at sea. Give my love and best wishes to all the folks and let them know I will write to them personally if I should survive the passage."

While at Hampton Roads, Craven’s crew made minor repairs to their ironclad. Tecumseh’s steering cables had parted, and the ship ran aground briefly while descending the James River. The cables were replaced, and the ship took on coal, ammunition, and supplies at the anchorage. Craven also ordered more ammunition to be sent ahead to Pensacola. Twelve new crewmembers were added from the steam frigate USS Minnesota. saved by the Monitor from the CSS Virginia in the same waters two years earlier. The Monitor was gone, sunk at sea in a storm off Cape Hatteras at the end of 1862, most of the crew rescued by the vessel towing her. Tecumseh would be transiting the same waters and would be towed to Pensacola by the steam gunboat USS Eutaw, accompanied by the side-wheel steamship USS Augusta. Tecumseh and her escorts sailed from Norfolk on July 5, 1864, and headed south.

Click Here to read part two.

Related Battles

322

1,500