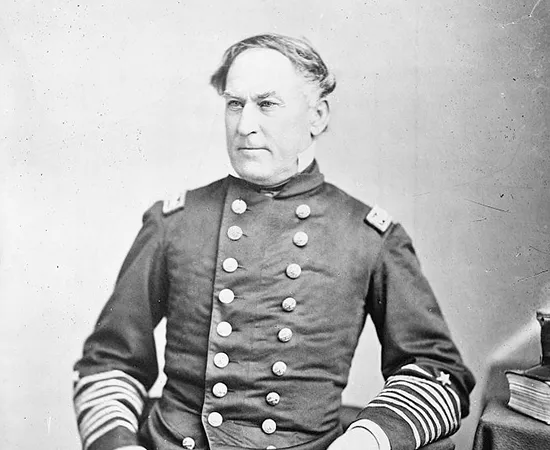

By the spring of 1864, Rear Admiral David G. Farragut had developed a case of “Monitor Fever.” Since early in the war, when he was named to command the Gulf Coast Blockading Squadron, he had envisioned capturing the strategic Confederate city of Mobile, Alabama. Mobile was the South’s largest open port on the Gulf of Mexico and a frequent haven for blockade runners. From there, two railroads connected the city to the Confederacy’s interior. Farragut’s orders sending him to capture New Orleans in early 1862 had included Mobile as his next objective. Still, the army campaigns against Vicksburg and Port Hudson in 1862 and into 1863 required the cooperation of his big, deep-draft wooden warships. By 1864, a joint army-navy move against Mobile had been agreed to draw troops away from William T. Sherman’s advance into northern Georgia. Watching ironclad Union gunboats and Confederate rams operate on the Mississippi River had shown Farragut the effectiveness of armored vessels. With the army now ready to provide an infantry force, Farragut, by then a keen observer of Confederate activity in Mobile Bay, told navy secretary Gideon Welles that a fleet action against Mobile would require at least “one or two” monitors to counter any rebel armored warships.

Farragut was especially concerned about the ironclad ram CSS Tennessee. The Tennessee was a powerful threat to his fleet: her 18-inch thick wood casemate was plated with six inches of armor, and she carried two 7-inch and four 6.4-inch Brooke rifled guns, both highly effective against wooden ships. She also carried a wrought-iron-plated ram on her bow. The Tennessee was operational by early May 1864. The lightly-armed gunboats CSS Selma, Morgan, and Gaines provided escorts for the big ram, and the flotilla was commanded by the experienced Admiral Franklin Buchanan, the commander of the CSS Virginia at Hampton Roads. Two other smaller ironclads were also nearly completed, Farragut learned, and could soon join Tennessee. On May 24, Tennessee descended lower Mobile Bay to the shelter of Fort Morgan in the clear view of the Union fleet offshore. “A rather ugly brute she is,” thought one Union officer. Farragut inspected the Tennessee from a distance and concluded more firepower would be necessary. He traded messages again with Welles and, on June 25, learned four ironclads would be headed his way. The river monitors USS Chickasaw and USS Winnebago, each with two turrets and four 11-inch guns, would be released from their duties on the Mississippi and sent to Farragut at Pensacola. Joining them with their big 15” guns would be the newly-commissioned USS Manhattan from New York and her sister Tecumseh from Norfolk.

Tecumseh’s transit south to Pensacola was delayed six days in Port Royal, South Carolina, after she developed engine trouble. On the morning of July 16, 19-year-old landsman James Dalton from New York wrote a letter home to his father:

"Today at eight o'clock, we leave for our destination Mobile. We will get there in about twenty days, being one thousand miles from here and we cannot steam fast. I am disappointed in not seeing [brother] Johnny at this place before I leave... Give my respects to everyone and let them know all is right with me at present. from your affectionate son, James L. Dalton"

Dalton requested that his father post any further letters to New Orleans, presumably Tecumseh’s destination, once Mobile had been captured. Tecumseh and the Eutaw arrived at Pensacola on July 28 and joined Farragut’s fleet; many of the other ships were already gathering near Mobile Bay, just 50 miles west. Manhattan had been there since July 8, Winnebago arrived from New Orleans on August 1, and Chickasaw a day later. As on the James River, Craven was given command of all four monitors and soon learned that he would be leading the fleet into battle.

While waiting for Tecumseh to arrive off Mobile, Farragut and his officers observed the Confederate defenses. The opening into the bay from the gulf was about three miles wide and guarded by strong brick fortifications at the east and west ends. To the west, Fort Gaines stood at the tip of Dauphin Island. Twelve of its 26 guns faced the bay but were out of range of the ship channel. On the eastern end, Fort Morgan stood at the end of Mobile Point. Built between 1819 and 1834, the three-tiered brick fort mounted 46 guns, primarily 32-pounders, 10-inch Columbiads, and 7- and 8-inch Brooke rifles. About 38 guns could face the channel, only 500 yards away. Outside the fort along the beach, another battery of seven guns bore down on the channel from point-blank range. In addition to the forts, a row of sunken piles stretched from Fort Gaines eastward, almost entirely across the harbor entrance. During June and July, the Confederates laid 180 torpedoes in three staggered rows from the end of the piles to the ship channel, just under the guns of Fort Morgan. The open channel was narrow, and a black buoy marked the eastern end of the torpedo field so blockade runners could safely enter and leave the bay.

The Union attack plan was simple but bold. Fort Gaines would be the objective of 2,400 army troops landing on the remote, western end of Dauphin Island two days before the fleet assault. With Gaines secure, Farragut’s fleet could focus its attention on passing up the channel in front of Fort Morgan. Once inside the bay, the ships could maneuver against the Tennessee outside the range of the fort’s guns. The monitors, led by Craven onboard Tecumseh, would lead the battle line and go in first. Tecumseh and Manhattan, with their big 15-inch guns, would focus on keeping the Tennessee away from the wooden ships, while the Winnebago and Chickasaw, with their 11-inch guns, would reduce the battery on the beach and deal with the Gaines, Morgan, and Selma. The line of big sloops-of-war, led by the USS Richmond, would follow the monitors to port and focus on knocking out Fort Morgan’s batteries while moving into the bay as quickly as possible. USS Hartford, Farragut’s flagship, would be in line behind the Richmond, followed by the rest of the fleet. Farragut ordered the big ships lashed together in pairs with the smaller vessels on the port side away from Fort Morgan to shorten the line of ships and protect his smaller gunboats. USS Octorara would be protected by Brooklyn, USS Metacomet would be tied to Hartford’s side, and so on down the line. Farragut knew about the torpedoes; his officers had watched the Confederates lay many of them in the weeks before the assault. He briefed his ship captains on August 3 and gave them written orders:

"There are certain black buoys placed by the enemy from the piles on the west side of the channel across it towards Fort Morgan. It is understood that there are torpedoes and other obstructions between the buoys, the vessels will take care to pass to the eastward of the easternmost buoy, which is clear of all obstructions. "

A total of 18 Union warships with 190 guns would attempt to pass the forts and torpedoes and destroy the Confederate flotilla waiting inside the bay. At Pensacola, Tecumseh was delayed nearly six days as more engine repairs were made. Farragut was anxious to have the monitor report to Mobile Bay and join the others quickly, as the army attack on Fort Gaines was set for August 3. Many of Tecumseh’s crew were sick from the voyage and had been sent to the hospital. Most of the sick men worked in the ironclad’s furnace-like engine and boiler compartments. One of them was Peter Holland, sent to work as a coal heaver after his gunshot to the face received on the James River had healed.

She was ready by 10:00 a.m. on August 4 and departed Pensacola under tow. Tecumseh arrived at Farragut’s fleet anchored off Mobile Bay six hours later, in time for Craven to meet with Farragut in his flag cabin on the Hartford. Craven apologized, saying, “I regret, Admiral, that I have detained you.” Farragut reviewed his orders and the battle plan for the next morning’s attack with Craven. The meeting ended, and Craven went back to his ship. That evening, on Tecumseh and the other warships of the fleet, men prepared for battle. All hands were called to quarters at 5:30 a.m. on August 5, and the fleet was soon ready to get underway. Craven climbed up through Tecumseh’s turret into the pilot house, where he was joined by local civilian harbor pilot John Collins. Collins was responsible for guiding Craven up the channel into the lower bay without running aground. The four monitors, Tecumseh in the lead, followed by Manhattan, Winnebago, and Chickasaw, were slower and moved north toward the channel first. The monitors put their boats in the water and towed them to provide clear fields of fire for their guns. All deck hatches were closed tight, and the turret rotation mechanisms were tested. The big sloops formed up in line behind the monitors and to port, lashed in pairs to the gunboats. All the warships flew massive national flags from their mastheads. One seaman remembered that every sailor “could see the mass of colors grandly unfurled by the strong westerly breeze.” The gunners in Fort Morgan were ready too, as were the Tennessee and her escorts just inside Mobile Point.

Onboard Tecumseh, Executive Officer Kelley, in charge of the gun crews inside the turret, steadied his men. “Our enemy is brave and determined, and he will not flinch or give up until forced to do so. So we must do our very best, shoot quick and true, exactly as if the odds were all against us,” Kelley told them. Seaman Cousins manned one of the guns. “When nearly opposite Fort Morgan, our commander ordered the 15-inch shells to be discharged at the fort and the guns to be loaded with solid shot preparatory to engaging the ram [Tennessee].” At 6:47 a.m., Tecumseh opened the battle with a well-aimed, 350-pound shot that struck the lighthouse next to the battery on the beach, sending bricks and mortar everywhere. Gunfire quickly erupted from the other monitors, and the gun crews inside Fort Morgan returned fire. The Confederate gunners used their big rifles on the monitors, reserving their smoothbores for the wooden ships. Farragut’s sloops opened fire as they moved north and came within range. Soon the channel was enveloped in smoke that settled toward the fort as both sides blazed away at ranges of a few hundred yards or less.

In the lead, Collins guided Craven and Tecumseh north and slightly east up the channel under heavy fire. “We did not fire more than two shells at the fort,” wrote a handful of crewmen after the battle, “but were reserving our next broadside for the rebel ram. When about abreast of Fort Morgan, the order was given to go ahead at full speed.” Frank Cousins’ gun crew loaded solid shots with 45 pounds of powder into the huge 15-inch muzzles as Tecumseh’s turret rotated in search of the Confederate ironclad.

As Tecumseh passed the fort, Craven took in the scene through the small viewing ports in the pilot house armor plate. Immediately astern, the Manhattan and the other monitors followed in Tecumseh’s wake. Behind him on his port side, Farragut’s faster ships were gaining on the line of ironclads. To his front, slightly to the right, Craven could now see the black buoy marking the eastern end of the torpedo field. The open channel was to the right of the buoy. Unexpectedly, to Craven’s left, he saw that the Tennessee and her escorts had moved westward from their usual anchorage behind Mobile Point and had positioned themselves across the channel on the far side of the torpedoes, just a few hundred yards away. Tennessee’s guns could rake the Union warships from that position as they approached the torpedo field. Pilot Collins dutifully reported deep water to starboard as the channel bent to the northeast. Craven now realized he could not comply with all of Farragut’s orders. To bear to the right and clear the buoy as the ship captains were told to do, Tecumseh would have to execute a sharp turn back to the left to close with the Tennessee once past the torpedo danger. Craven knew his ironclad could not turn sharply even at full speed, and he knew that Tennessee would have her way with the Brooklyn, coming up fast, while Tecumseh and Manhattan took time to maneuver. To bear to the left across the torpedo field was the shortest route to the Confederate ram, his primary objective for the attack. “The admiral ordered me to go inside that buoy, but it must be a mistake,” Craven told Collins. Craven gave the order to turn to port.

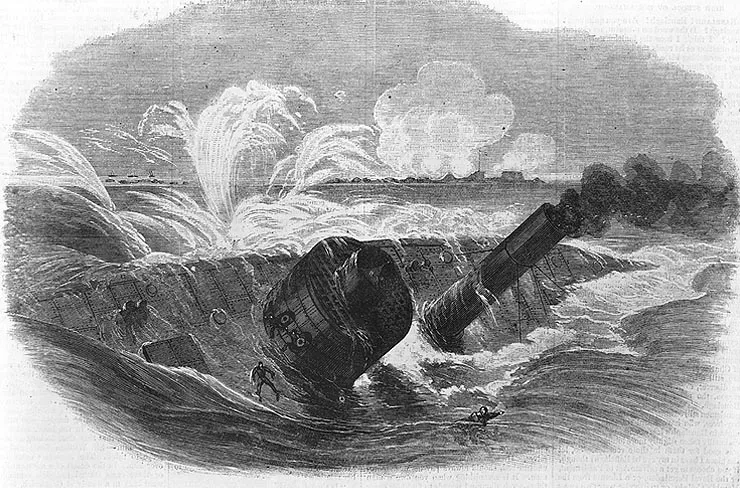

A few minutes later, at around 7:40 a.m., a violent underwater explosion rocked the Tecumseh. The torpedo detonated forward on the starboard side, directly below the turret. The monitor careened over to port with the force of the blast, briefly burying her port side under the waves. Inside the ship, the water “rushed up into the berth deck and turret chamber, where nothing but confusion and despair reigned,” recalled a few survivors. Acting Master Gardner Cottrell was below decks when the torpedo exploded:

"I was fortunate enough to be on the berth deck, just under the turret, at my station in the powder division, when the shock came and the sea began to pour in. I shouted to the few men near me to climb up through the turret, and joining them, all of us hurried to keep ahead of the water. We crawled through the fifteen-inch gun port, and among the last, I reached the deck as the ship gave a lurch and settled heavily. Running to the side, I jumped overboard and struck out as hard as I could, fearing to be sucked down with the Tecumseh, which I realized was hopelessly lost. "

Gunners Mate Samuel Shinn, under the turret with Cottrell, remembered the explosion:

"Such a sensation I never experienced before or never care to again. It seemed as if we were lifted right out of the water. At the same time, a blinding flash like lightning came through the porthole. A large hole was stove in the vessel's side, and the men below commenced to cry that the vessel was sinking. I started out of the porthole and told Lieut. Kelley to follow, but he stood there dazed and apparently unable to move. Just as I was climbing out of the porthole, the old Scotchman who was in charge of the gun said: Lieutenant, shall I fire?' I said: 'For God's sake, wait until I get out…' I was followed by several more of the gun crew, who got out through the porthole."

The closed deck hatches on the main deck prevented most of the crewmen below decks, especially those in the engineering compartments, from escaping the rapidly sinking ship.

Momentum rolled Tecumseh back over to starboard, where she briefly wallowed in the swells, burying her bow as the water rushed in. In the pilot house, Craven and Collins made their escape, descending the ladder into the turret where the water was already up to their waists and quickly rising. Both men reached the bottom of the ladder leading up through the turret top at the same time. With a gesture that would be venerated for decades in stories of navy honor and tradition, Craven stepped aside, saying: “After you, pilot. I leave my ship last.” Collins reached the top of the turret, recalling later that "There was nothing after me. When I reached the topmost round of the ladder, the vessel seemed to drop from under me."

As her bow pitched down, Tecumseh’s design improvements worked against her. The heavy 15-inch guns with their massive carriages and the extra armor plating on the top and around the bottom of the turret, all of it far forward on the bow, helped to drive her under. Less than two minutes after the blast, Tecumseh plunged toward the bottom, rolling over to starboard as she went. As she turned over, her propeller cleared the surface as she slipped under. “Her stern lifted high in the air with the propeller still revolving, and the ship pitched out of sight like an arrow twanged from a bow,” one witness on the Manhattan recalled. Another sailor recalled that “immense bubbles of steam, as large as cauldrons,” rose to the surface as the monitor disappeared. The Tecumseh was gone.

Several of her crew struggled to survive as the ship went under. “The gun's crews and those that were in the pilot house succeeded in getting out before she settled down beneath the waves,” a handful of survivors told later. “We had three boats towing alongside, two of which were immediately filled and were swamped.” Frank Cousins managed to cut the line holding the third boat to the ironclad, freeing it from plunging down with the ship. Gardner Cottrell nearly drowned as the sinking monitor dragged him under:

"Although a good swimmer I was not able to get far enough away, and soon I felt myself pulled under the surface, as I had feared I should be. It seemed an eternity before I came to the top again. I was nearly exhausted, but I struggled to regain my breath and had barely succeeded when a heavy wave came along from I don't know where and swamped me entirely. I supposed I was born to be hanged, for once more I saw the light of day, filled my lungs with fresh air, and managed to keep afloat by treading water. It seemed a long while, yet probably it was very short before I was picked up by one of our own boats…"

Cottrell and six other men, including Cousins, Samuel Shinn, and Peter Parker, were able to climb aboard the boat. “We got into the cutter and pushed away just before the monitor tipped over and sank,” recalled Shinn.Around 14 men were still in the water. Fortunately for them, Tecumseh sank in full view of the other Union warships, so help was soon on the way. Farragut watched in horror on the flagship Hartford as the Tecumseh sank and her survivors were washed into the bay. “Pick up those poor fellows,” he ordered Captain James Jouett of the Metacomet, lashed to Hartford’s port side. Within minutes, Acting Ensign Henry C. Nields from Metacomet led a rescue boat crew within 600 yards of Fort Morgan’s guns into the torpedo field through what Farragut called “one of the most galling fires I ever saw.” As shots and shells flew all around, Nields’ sailors pulled ten men from the water. For their actions that morning, six of the men in Nields’ boat were awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor. Four more of the Tecumseh survivors were able to swim to Mobile Point, where they were captured by the Confederates. They had survived their ship’s sinking but soon found themselves headed for Andersonville prison.

Of Tecumseh’s complement of around 115 officers and sailors on August 5, only 20 survived the sinking. Civilian pilot John Collins also survived. Drowned were Commander Tunis A. Craven, Executive Officer John Kelley, Chief Engineer John Faron, Paymaster George Work, and eight other officers. Among the sailors, Daniel Taber, Michael Hoban, Thomas Brown, James Dalton, and some 80 others went down with their ship. Frank Cousins survived with his back pay wrapped in his handkerchief, and Peter Parker survived his second navy shipwreck. Of the 12 borrowed crewmen from the Owasco, only one survived.

Meanwhile, Craven’s turn to port into the torpedo field had thrown the rest of the fleet into chaos. As Tecumseh turned left, she crossed in front of the line of big sloops. On the lead vessel pair, Captain James Alden stopped the Brooklyn and Octorara to avoid a collision with the ironclads. “The monitors are right ahead; we cannot go in without passing them,” Alden signaled to Farragut. As he watched Tecumseh founder, Alden signaled again, “We have lost our best monitor.” The gun decks of the ships ran red with blood as the crews were cut to pieces by Fort Morgan’s guns. Farragut watched the collapse of his whole battle line. As the big ships slowed or stopped and piled up behind Brooklyn, Farragut faced the same decision Craven had faced just minutes earlier. To readjust the whole line and turn starboard safely up the channel would take time, all the while, his crews would suffer even heavier casualties from the guns of the fort. Across the torpedo field just ahead and to the left, the Tennessee waited. Farragut wasted no time making up his mind. He ordered Captain Percival Drayton of the Hartford and Jouett of the Metacomet to turn to port. Both ships backed their engines at full power as their bows swung to the left of the stalled Brooklyn. Once clear, both captains ordered full ahead. As Hartford and Metacomet lurched forward and passed the Richmond, Farragut was warned of the upcoming torpedo field. “Damn the torpedoes! Four bells! Captain Drayton, go ahead! Jouett, full speed!” The remaining ships followed Hartford and Metacomet across the torpedoes and into Mobile Bay. Many of the crewmen remembered hearing inert torpedoes bumping along the bottoms of their ships as their firing pins snapped but failed to detonate.

By the end of the morning, Farragut’s fleet had won the Battle of Mobile Bay. The Union fleet severely battered the Tennessee, especially by the monitors Manhattan, Chickasaw, and Winnebago. After three hours of battle, Tennessee surrendered. Her escorts, Morgan, Selma, and Gaines, were driven off, captured, or sunk. Fort Gaines surrendered to the army on August 8, and Fort Morgan capitulated after a two-week-long bombardment and siege, surrendering on August 23. A week later, the city of Atlanta fell to Sherman’s army. The two Union victories helped cement President Abraham Lincoln’s reelection in November and turned the tide of the war in the Union’s favor. Although Mobile Bay was closed to blockade runners, the city of Mobile held out. Torpedoes in the upper bay claimed nine more Union vessels, including the monitors USS Milwaukee and USS Osage, in March 1865. Mobile finally surrendered that April, the same week Confederate armies surrendered in Virginia and North Carolina.

Tecumseh’s story did not end with her sinking. Parties interested in raising the vessel expressed their interest to Farragut as early as November 1864, but the admiral was more interested in recovering the 15-inch guns from the ironclad. He wrote Secretary Welles that:

"The Tecumseh is buoyed and lies very near Fort Morgan, say two or three hundred yards from the wharf in seven fathoms of water, with three fathoms over her. We have not been able to ascertain her condition, not being able to discover her turret. Much valuable material and her guns may be recovered, provided good divers are employed on this duty."

As the first iron warships designed to operate against enemy vessels in rivers and coastal waters, few can question the significance of John Ericsson’s monitor design. Three-quarters of all Union warships built during the Civil War were monitors. Including the original Monitor, 60 of her type were built, and 37 were commissioned. Only six monitors were lost during the war, none were sunk by Confederate gunfire: Tecumseh, Patapsco, Milwaukee, and Osage were sunk by torpedoes; Monitor and Weehawken were foundered in rough seas. Two Confederate ironclads were captured after engagements with monitors, the Tennessee at Mobile Bay and the Atlanta after battling with the Weehawken and Nahant.

Tecumseh’s short career as a warship in the U. S. Navy lasted only 108 days. Her role as an important warship in naval history will always be eclipsed by John Ericsson’s original Monitor of 1862. Few will ever read about Tecumseh dodging Confederate torpedoes and destroying artillery batteries on the James River. Commander Craven’s heroic words, “After you, pilot,” will always be overshadowed by Farragut’s “Damn the torpedoes, full speed ahead!” Yet the 94 officers and men still aboard Tecumseh at the bottom of Mobile Bay deserve to have their ship’s story told too.

Click here to read part one.

Related Battles

322

1,500