“Great Spirit and Vigor”

In the summer of 1775, the Continental Congress began preparations for the United States’ first military incursion onto foreign soil: a campaign to capture Quebec, Canada. By spring 1776, however, mismanagement and disease has severely hampered the American efforts to besiege the city, and British reinforcements allowed the governor of Quebec, General Guy Carleton, to launch a counteroffensive. Carleton broke the siege, and the Americans abandoned their captured territory in Canada. They retreated to New York along the Richelieu River and Lake Champlain – a long, narrow lake running along the border between New York and Vermont.

The British general pursued the Continentals with much of the garrison of Quebec, harassing them on their retreat. Carleton had an ambitious plan to drive into New York in hopes of linking up with the British forces that had recently captured New York City. This maneuver would split off the New England colonies from the Mid-Atlantic and South. The Patriots, for their part, tried to slow Carleton’s progress by seizing or destroying all the ships they came across as they retreated upriver, and they eventually fortified themselves at Forts Crown Point and Ticonderoga at the southern end of Lake Champlain. Control of the lake was especially vital, because it was nearly impossible for an army to move through the dense wilderness of upstate-New York without relying on waterways for transportation.

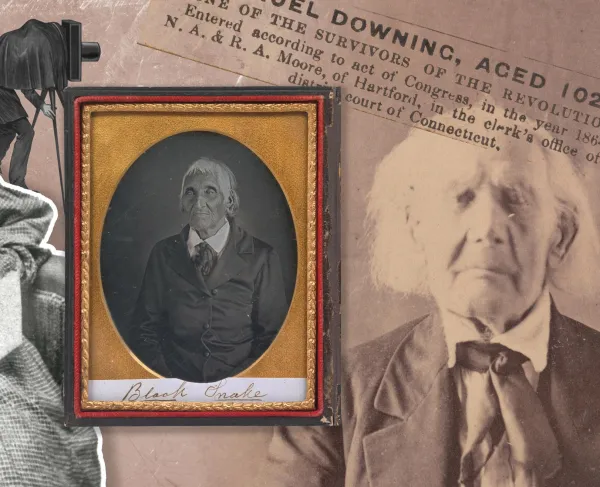

With their land forces badly outnumbered, the Americans formed their captured ships into a small naval squadron to slow the British advance. They augmented the ships with additional vessels constructed on the scene.Shipwrights arrived from the colonies to build a fleet.The majority of the vessels built were gunboats (called “gondolas”) – flat-bottomed boats powered by oar or sail that carried three cannon and forty-five men. The Patriots also constructed several larger galleys which carried six guns and were more maneuverable than most ships in the fleet. There were few sailors in the New York wilderness, so the vessels were manned primarily by hastily-trained infantrymen. General Horatio Gates, who had recently assumed command of the army on Lake Champlain, soon delegated command of the American fleet to General Benedict Arnold, a former ship captain who had gained prestige earlier in the Canadian campaign for his role in the capture of Fort Ticonderoga.

Recognizing the need to control the lake, Carleton began assembling his own small fleet in late spring. This force consisted mainly of Royal Navy warships that were disassembled and transported to Lake Champlain and “prefabricated” ships from Great Britain which were shipped to Canada ready-to-assemble. The British general supplemented these ships with gondolas of his own. With superior resources at his disposal, Carleton’s shipbuilding quickly overtook the Americans. By October, Carleton had a fleet of over thirty armed vessels compared to the Americans’ fifteen. The British fleet also had more (and heavier) guns, and hundreds of veteran sailors. Carleton placed this force under the command of Royal Navy Captain Thomas Pringle, who sailed south onto the lake to meet Arnold on October 9, 1776.

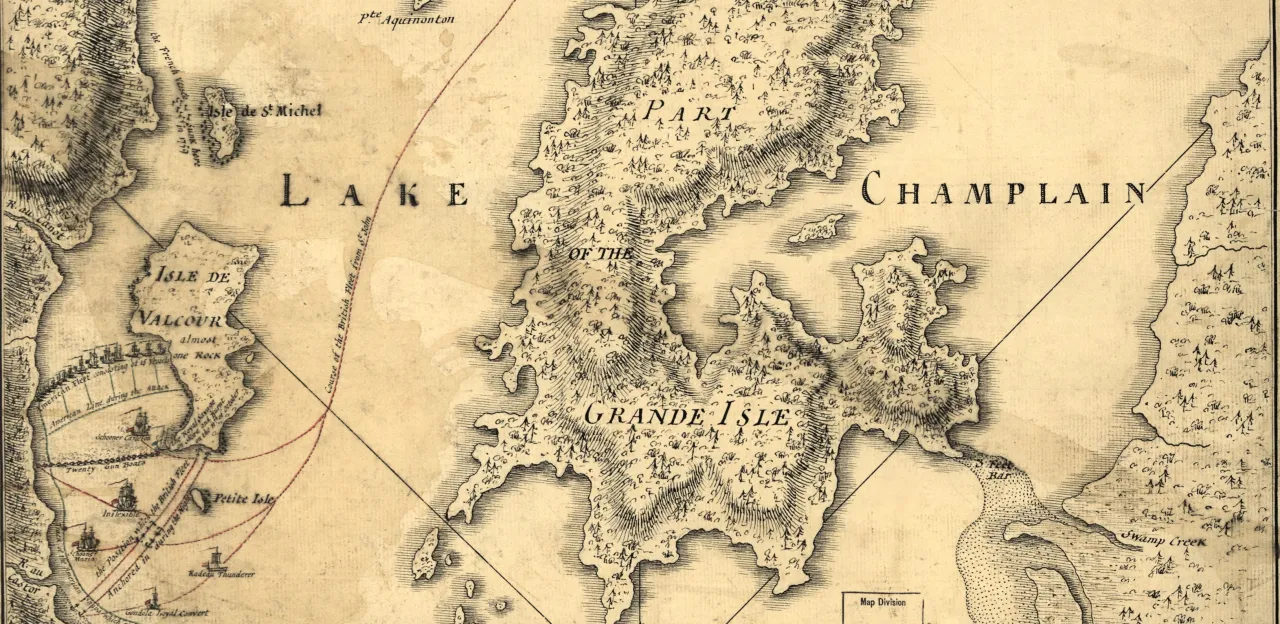

Arnold was prepared, and arrayed his fleet in a sheltered inlet between the lakeshore and Valcour Island, one of many forested islands dotting the lake. The British were forced to move past the inlet before they could see Arnold’s location, then sail upwind into the inlet in order to engage the Americans. This significantly meant that many of the larger British ships – which were not rigged to sail upwind and did not have oars – fell behind the smaller gunboats, and could not support them in the early stages of the battle. The confined location also limited the ability of the experienced British crews to outmaneuver the Americans.

These advantages were useful when combat began around noon, but were gradually overcome by Pringle’s superior fleet. Almost immediately, one of the larger American ships ran aground and was abandoned when the adverse winds prevented it from reaching its position in Arnold’s battle line. Nevertheless, the Americans held their own for five hours as the British crept upwind, and a handful of vessels on each side were destroyed or disabled as the two forces pummeled each other. The larger ships, as they reached the battle, were especially threatening to the small gunboats, making them prime targets. The British schooner Carleton, for example, lost nearly half its crew to concentrated American fire before it was towed to safety. By dusk, HMS Inflexible (which was the most powerful ship on the lake, with 22 cannon) came into action, but with the light fading and the British gunboats low on ammunition, Pringle recalled his fleet.

The British anchored near the mouth of the bay and dispatched Native American allies to occupy the shore to prevent the Americans from abandoning their ships and escaping. A foggy, night, however, enabled Arnold to quietly slip through a gap in the British defenses and sail what remained of the fleet south towards Crown Point. The next morning, the British noticed their mistake and caught up to the damaged American ships. They first captured the galley Washington, and it soon became clear that they would overtake most of the remaining vessels. Only four American ships were fit to escape. To avoid capture, Arnold grounded the remainder and burned them – personally setting fire to his flagship. The exhausted men then retreated overland to Crown Point. However, British control of the lake and the destruction of most of the American fleet made even this position indefensible, and the Americans destroyed the fort and withdrew to Fort Ticonderoga.

The battle itself was unquestionably an American loss. About sixty Americans were killed or wounded, over one-hundred captured, and eleven vessels were destroyed (including those that Arnold burned). By comparison, the British lost three gunboats and suffered about forty casualties. However, despite the defeat, the simple existence of the American fleet had forced Carleton to delay all summer while he constructed a force to seize Lake Champlain. By the time he occupied Crown Point and spent two weeks planning for an attack on Fort Ticonderoga, winter was setting in; Carleton was unwilling to risk launching an offensive with so little time before he would need to establish winter quarters for his army. Consequently, the Patriots’ shipbuilding efforts gave the Americans in northwestern New York time to prepare for the British invasion the following year – contributing to the critical victory at Saratoga.

Related Battles

200

40