The Capture and Burning of Washington, D.C.

The burning of Washington, D.C., in 1814 was one of America’s darkest hours. The new republic that had been created by the Founding Fathers less than a half-century earlier was in peril. Culminating in a flurry of disastrous British-American interactions that resulted in war - the War of 1812 acted as a pseudo-Revolutionary War that further solidified the United States’ legitimacy as a new nation independent from the British Empire. Since the Revolutionary War, America and Britain were not on good terms. The British navy continually captured American sailors on the high seas, as well as assisted Native American tribes against American expansionist efforts. The most famous of these campaigns is Tecumseh’s War, in which Tecumseh, a Native American chief, led a war against American forces expanding into the region of the modern-day state of Indiana. The American forces, led by William Henry Harrison, won, however, congressmen back in Washington, D.C. blamed Britain for providing aid to Tecumseh and his multi-tribe confederacy. By 1812, Britain was slowly phasing out America from trade in favor of their colonies in Canada and the Caribbean. Americans feared losing Great Britain as a trade partner, as Britain was one of the two major world powers at the time.

The War of 1812 began when war-hawks (government officials who wanted to go to war) pushed for a war bill on June 12th, 1812 in response to Britain’s actions against American interests. In 1812, with the assistance of Napoleon Bonaparte, the United States implemented a trade embargo against Britain in favor of French trade, in return the French would stop attacking American vessels.

The two years leading up to the burning of Washington DC were spent primarily in Canada with a stalemate between British and American forces. The British military in the War of 1812 was not the entirety of the British Army & Navy, rather it was a detachment from the main army that was currently fighting the Napoleonic Wars in Europe. America’s military, however, was not strong due to Congress’ unwillingness to dedicate much needed trained soldiers to fight in the war. Nor could politicians agree on the size of the American Army & Navy. The United States relied primarily on the use of citizen-led militia groups, who were not nearly as effective compared to trained regular soldiers. Both British and American forces were unable to make a dent in either’s armies. Neither side could hold and occupy territories for an extended period of time. It was not until the British began their campaign in the Chesapeake Bay when the British began implementing new strategies to try and win the war.

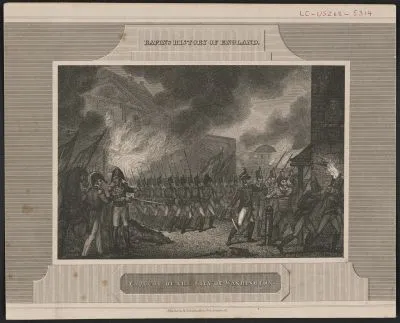

In August of 1814, the British began raiding the eastern shores of the United States in an attempt to dampen morale and the will to fight in the states. In 1814, Britain and a coalition of nations had recently defeated Napoleon and his army, so Britain’s resources could be directed almost entirely towards the war in America. Britain wanted to invade the southern regions of the United States to move American forces away from Canadian territory. The British chose to assault two cities: Washington, D.C., and Baltimore, Maryland. They chose Washington due to its lack of defenses and easy access from the Chesapeake Bay, and Baltimore due to its importance in ship manufacturing and trade in the Baltimore Harbor. On August 24th, 1814, the Battle of Bladensburg took place outside of Washington, resulting in an embarrassing American defeat. The defeat at Bladensburg allowed for the British soldiers led by Major General Robert Ross to enter the nation’s capital.

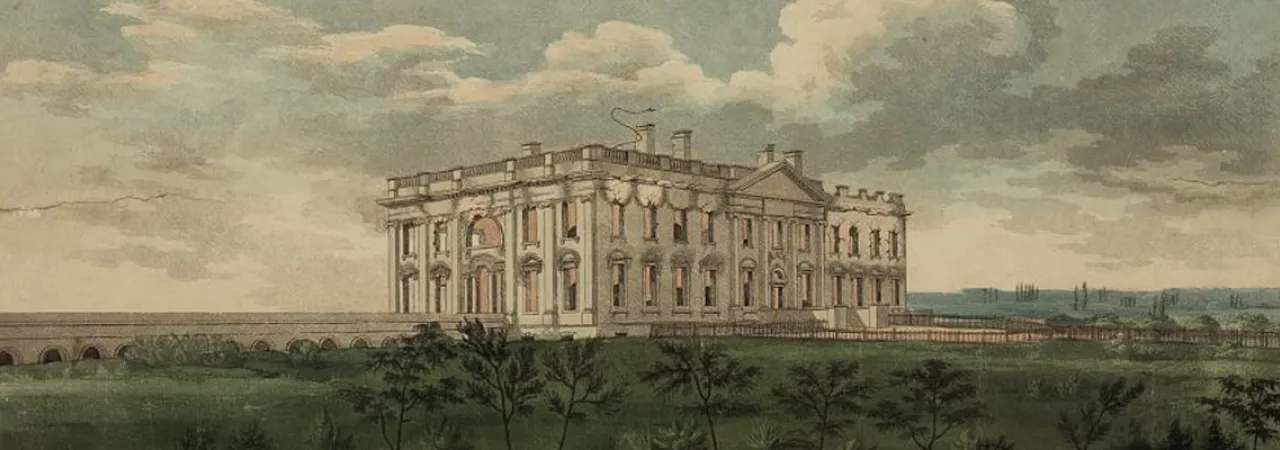

Later that August 24th evening, British soldiers moved on Washington holding bitter resentment for the American burning of the Canadian capital of York (present-day Toronto) in 1813. When entering Washington, the British and Canadian soldiers had unfettered access to the capital and began burning the city. Government officials were forced to flee the city. President James Madison and First Lady Dolley Madison both fled the White House. Before leaving, Dolley Madison had a portrait of President George Washington, and many other irreplaceable artifacts from the founding of the nation secured. Dolley had the artifacts taken for safekeeping from the flames. Washington’s naval yard was ordered to be set ablaze to prevent warships from being taken into British hands. British Admiral George Cockburn ordered his men to burn the White House, Capitol Building, the Library of Congress (located in the Capitol Building at the time), the Treasury, and other government buildings. However, Cockburn instructed his men to not destroy private residences, and they even spared the Patent Office due to the head administrator convincing the British that inside the building contained private property. The administrator argued that if the inventions within the Patent Office were burned that it would be a loss to humanity.

The following day on August 25th, a storm rolled into Washington and put out the fires. Unfortunately, during the storm, a tornado erupted and tore through the city. While the British had spared the private residences, the tornado did not express such mercy to private residences and destroyed some in the city. After the burning of Washington, there was widespread looting throughout the city, and many of the looters were American citizens. Shortly after the British were finished with burning Washington, they left almost immediately towards Baltimore as the British did not intend to occupy Washington.

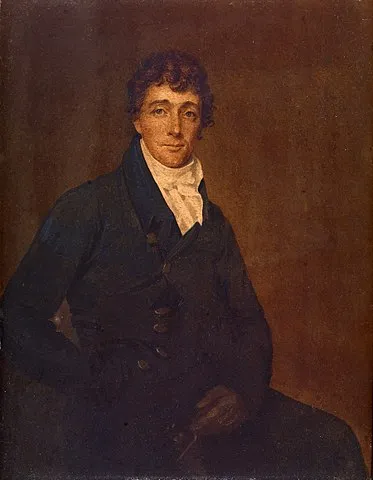

The burning of Washington did not achieve the effect that the British had hoped that it would cause. Instead of demoralizing Americans, it gave Americans a cause to rally behind in defeating the British once again. The burning of Washington negatively impacted the British, because when the British arrived in Baltimore, Maryland, on September 13th, 1814, the British navy was met with a well-defended city. The Battle of Fort McHenry ensued and resulted in an American victory. While the battle was raging, a Baltimore lawyer by the name of Francis Scott Key was held aboard a British warship and watched the battle unfold. He wrote a poem called the Defense of Fort McHenry, which later became the Star-Spangled Banner, America’s national anthem. The United States’ victory at Fort McHenry led to the eventual end of the war, with Washington left to rebuild from the fires.

The burning of Washington was not a large embarrassment as it was originally thought to be. Washington was quickly rebuilt, with the White House becoming operational in 1817 and the Capitol Building was operational by 1819. Overall, the burning of Washington symbolized that the young nation that was built upon democracy and freedom was able to take a major world power head-on and come out victorious. Thomas Law, a foreign visitor who went to Washington, described the city after the war like a phoenix rising from the fires stronger than ever before. The War of 1812 showed the world that America was a force to be reckoned with and would continue to be perpetual.

Further Reading:

- The Burning of Washington: The British Invasion of 1814: By Anthony S. Pitch

- Washington Burning: How a Frenchman's Vision for Our Nation's Capital Survived Congress, the Founding Fathers, and the Invading British Army: By Les Standiford

- Through the Perilous Fight: Six Weeks That Saved the Nation: By Steve Vogel

Related Battles

200

250