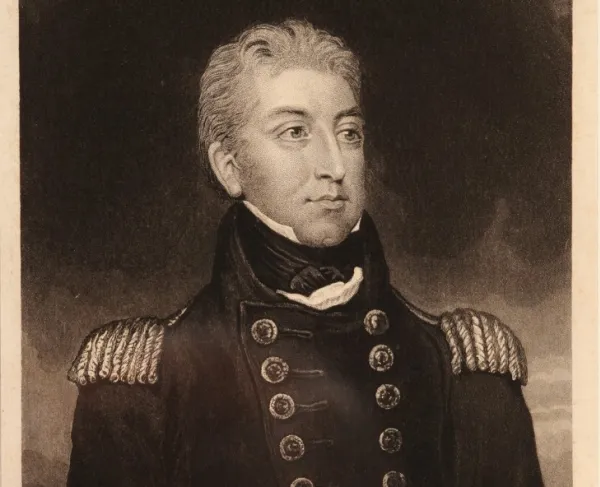

George Cockburn

Sir George Cockburn was born April 22, 1772, in London. Throughout his lifetime of service in the Royal Navy, he gained fame for taking part in many key sea battles during the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars. In American history, however, he is best known as the chief strategist and naval leader for the British attacks on Washington, D.C. and Baltimore, Maryland, during the War of 1812.

Born the second son of Sir James Cockburn, a Baronet, the younger Cockburn knew from an early age he would not inherit his father’s fortune and title. As a result, he pursued a career as an officer in the Royal Navy. Cockburn joined the service in March 1781 as a servant aboard the frigate, HMS Resource. He worked his way through a series of postings until he qualified as a midshipman aboard the frigate HMS Hebe in 1791.

As a midshipman, Cockburn was responsible for learning all the duties and skills required to become a lieutenant, the first commissioned rank in the officer corps. In addition to their training, midshipmen acted like non-commissioned officers, leading gun crews, repair parties, and acting as a bridge between the officers and the enlistees. After two years, Cockburn stood for the lieutenant’s exam and passed. After commissioning, his first assignment was to the brig HMS Orestes, shortly transferring to serve aboard the HMS Victory, the flagship of Britain’s Mediterranean Fleet.

Cockburn impressed his superiors, evidenced by his selection to command the sloop HMS Speedy just months later, while still a lieutenant. In January 1794, he received the command of HMS Inconstant, a frigate. The Royal Navy promoted him to the rank of Captain not long afterward. Still assigned to the Mediterranean Fleet, he took part in the blockade of Livorno and commanded a frigate in the Battle of Cape St. Vincent in 1797. Cockburn’s exemplary service and connections enabled his rapid rise through the ranks to continue.

After a series of postings in the far east and in European waters, in 1809 Cockburn was tasked to lead an expedition against the French colony of Martinique in the Caribbean. He captured the island and its entire garrison, and for his actions he received a motion of thanks from the British Parliament. After taking part in an unsuccessful spy mission to rescue the imprisoned King of Spain, Cockburn commanded a frigate during the siege of Cadiz, where he managed the transfer of supplies in rowboats from the fleet to the British garrison. After another batch of assignments, Cockburn was promoted to rear-admiral in August 1812.

The U.S. declared war against Britain in June 1812, after years of trade restrictions and impressments due to Britain’s war with France. While American troops invaded Canada, battles at sea commenced. In November 1812, Cockburn was chosen to lead a British squadron tasked with operating in and around the Chesapeake Bay. Cockburn’s fleet aggressively patrolled the American east coast contributing to a semi-tight blockade, burning American storehouses and raiding a number of coastal towns, especially in the Chesapeake. It was not until two years later, however, that Cockburn’s plan for the region would fully materialize.

Cockburn advocated for a strike at the heart of American resistance, at the capital: Washington, D.C. He secured the services of an expeditionary force commanded by his friend, Major General Robert Ross. Cockburn presented Ross with a plan to land a force of 4,500 soldiers and Marines north of Washington and attack the city from the landward side while a force of ships blasted through the defenses on the Potomac River. Ross, initially hesitant to risk a land campaign without any cavalry and little artillery, agreed, and the invasion began.

The ships anchored near Benedict, Maryland, on the Patuxent River in August 1814. The force, 3,500 soldiers and 1,000 Royal Marines, then began their march on Washington. Cockburn joined the march, acting as an advisor to Ross, while the ships sailed south and into the Potomac River. The British, contrary to Ross’ initial expectation, crushed American forces at Bladensburg on August 24, capturing Washington shortly thereafter. Cockburn oversaw much of the destruction that followed, with British troops burning government buildings and military stores, most famously the White House and Capitol. One of the only privately owned buildings burned was the office and printing house of the National Intelligencer, an American newspaper Cockburn disliked. He reportedly said during its destruction, “be sure that all the C's are destroyed, so that the rascals cannot any longer abuse my name.”

For his actions in the War of 1812, Cockburn was appointed a Knight Commander in the Order of the Bath in 1815. Cockburn continued to serve in the Royal Navy for another forty years, rising to the rank of Admiral of the Fleet and for a time serving as the First Naval Lord, the equivalent of the American “Chief of Naval Operations.” Shortly before his own death Cockburn inherited the Baronet title from his brother, who died without an heir. George Cockburn died on August 19, 1853, aged 81, and was buried in Kensal Green Cemetery in London.