The Battle of Fort Carillon (1758)

By July of 1758, the French and Indian War had been raging in North America for four years. What began as skirmishes on the edges of the French and British colonial empires had escalated and expanded into a wider conflict, known as the Seven Years War, with fighting in Europe, West Africa, India, and eventually even the Philippines. But for British Prime Minister William Pitt, the focus remained on North America. Pitt was determined to strip France of her colonial empire, and that meant conquering New France, which covered Canada and the land around the Great Lakes.

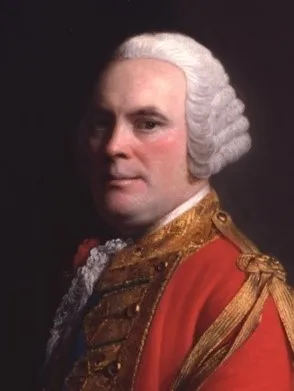

Pitt envisioned a grand campaign for 1758, with three simultaneous offensives by land and sea. One army would march into the Pennsylvania frontier and capture Fort Duquesne (on the site of modern Pittsburgh), depriving the French of the base from which their Indian allies had raided the colonial frontiers. An amphibious invasion would land on Cape Breton Island and capture the Fortress of Louisbourg, the “Gibraltar of the North,” to open the way for an invasion of Canada via the Saint Lawrence River. The final campaign was an offensive to open up the invasion corridor along Lake Champlain. To do this, General James Abercrombie was tasked with capturing Fort Carillon. The first two prongs of the British strategy would succeed, and set the stage for further victories in 1759. But Abercrombie would ultimately suffer defeat in the bloodiest battle of the French and Indian War.

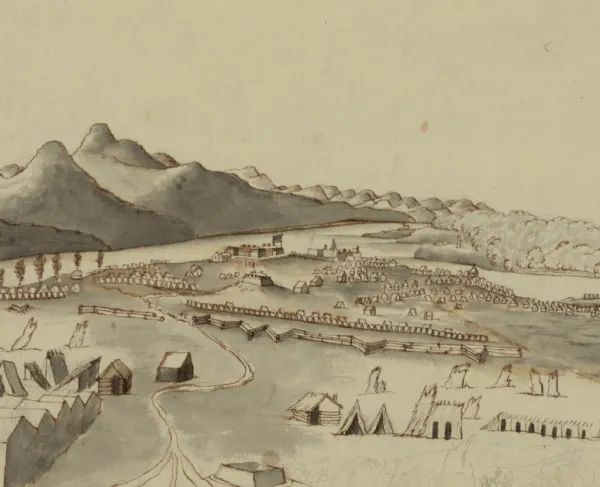

Fort Carillon had been constructed by the French in 1755. It was built at a point on the southern end of Lake Champlain called Ticonderoga, which was a Mohawk word for “the place between the waters.” It controlled the portage crossing between Lake George and Lake Champlain. To conquer Carillon, Abercrombie had at his command the largest army that had yet assembled in North America. It numbered more than twelve thousand men in total; six thousand were British regulars and the rest were provincial troops raised by the colonies. Among the regulars were regiments of Scottish Highlanders, renowned for their fighting prowess. Abercrombie also had a large train of artillery, for the anticipated siege of the fort. The army sailed in an armada of over eight hundred boats and landed near Fort Carillon on July 5, 1758.

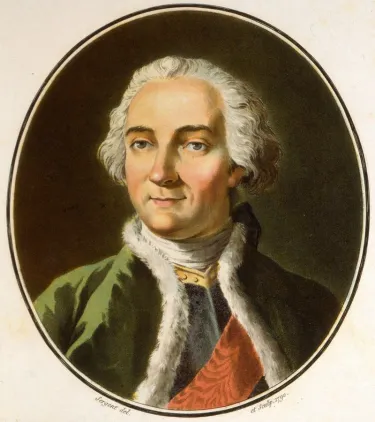

The commander of French troops in North America, General Louis-Joseph de Montcalm, the marquis de Montcalm, took command at Fort Carillon to stop the British invasion. To defend against Abercrombie’s twelve thousand men, Montcalm had less than four thousand soldiers. To make matters worse, Fort Carillon itself was not fully completed, so it would not withstand a long artillery bombardment. If the fort was besieged, it had only enough food for nine days. Montcalm decided to take a risk and meet the British outside the unfinished walls. At a spot three-quarters of a mile from Fort Carillon, the French built log breastworks and constructed an abatis, a tangled arrangement of sharpened branches designed to snare and slow enemy infantry, similar to modern barbed wire.

General Abercrombie had a long record of service in the British army, but he was not an especially dynamic commander. To compensate for this, Pitt had assigned the energetic George Howe, the older brother of future Revolutionary War commanders Richard and William Howe, as Abercrombie’s second in command. But on the day the British army landed near Fort Carillon, Lord Howe was killed in a skirmish with the French. His death seemed to slow the entire army, and it was not until July 7 that Abercrombie began to reconnoiter the French defenses. The military engineer who Abercrombie sent to determine the strength of the French defenses reported that the position could be carried by storm, and Abercrombie decided to launch an infantry assault the next day without bringing up any of his artillery for support.

On the afternoon of July 8, 1758, the British began their attack. Abercrombie had planned for a single, coordinated assault on the entire French line, but coordination broke down quickly and various regiments made their attacks against different parts of the line at different times. The sharpened branches of the abatis broke up the British formations and disrupted their cohesion, while the French poured on a deadly fire from behind their breastworks. Abercrombie continued to order attacks throughout the day, but this only increased the number of casualties. An assault by the 42nd Regiment of Foot, the Black Watch, did succeed in getting past the abatis and reaching the French positions, but it ultimately failed to dislodge the defenders.

Abercrombie reported just under two thousand casualties, with more than 500 dead. The French suffered just over three hundred killed and wounded combined. Defeat for the British was compounded by humiliation when Abercrombie ordered his force to withdraw back to their base at the southern end of Lake George. The order spread panic through the ranks, as soldiers began to fear that a French counterattack was imminent. Abercrombie’s vast army returned to where it had begun its campaign on the evening of July 9, having retreated from an enemy force a quarter of its size which was in no state to pursue them.

Montcalm ascribed his improbable victory to divine intervention and ordered a massive red cross to be raised on the site of the battle. Yet the victory was not enough to turn the tide of the war. The other two British armies succeeded in their campaigns, capturing Fort Duquesne and Louisbourg. The next year, the French would destroy Fort Carillon and retreat into Canada.

The Battle of Carillon left a lasting legacy in the minds of British and American commanders who would contest the same ground in the Revolutionary War. Many of these officers believed Fort Ticonderoga to be impregnable, but Montcalm’s successful defense of the fort would never be repeated. Fort Ticonderoga would be taken by the Americans in a surprise attack in 1775, then abandoned in the face of a British siege in 1777, then abandoned again by the British after their defeat at the Battles of Saratoga.

Further Reading

-

Crucible of War: The Seven Years' War and the Fate of Empire in British North America, 1754-1766 By: Fred Anderson

-

The French and Indian War: Deciding the Fate of North America By: Walter R. Borneman