Everyday Life in the Jamestown Colony

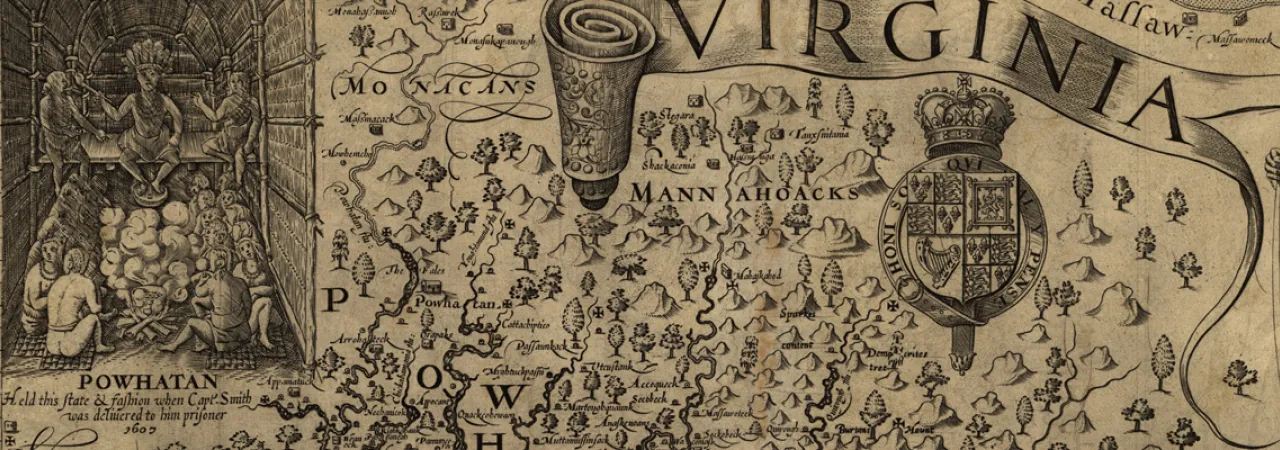

Few of the 104 English men and boys who set sail from England knew what to expect from their new home when they disembarked from their ships, the Susan Constant, the Godspeed, and the Discovery on May 14, 1607. Under a charter granted by King James I, these first English colonists to Virginia named their settlement Jamestown after their king, and the nearby river the James. Though this world was certainly new to them, these places already had names—the Algonquian-speaking tribes who inhabited the area knew the land as Tsenacomoco and the river, the Powhatan (named after the paramount chief of the Powhatan Indians). These English settlers would soon encounter the Powhatan and later, men and women from West Central Africa. All would have critical roles to play in everyday life in the Jamestown settlement as what began as a military outpost soon grew into a more stable colony with the introduction of the cash crop, tobacco.

Who lived in Jamestown?

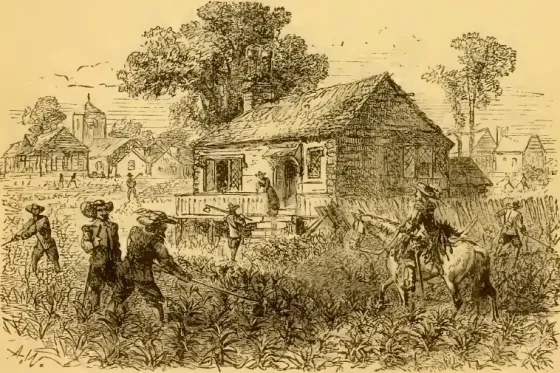

When the Virginia Company of London sent the first settlers to Jamestown in 1607, they only included English men and boys. Many of the first settlers were wealthy English gentlemen, but the list of first settlers also included laborers, bricklayers, carpenters, a blacksmith, barber, tailor, and a preacher. The first two English women arrived in 1608. More women, children, and family groups began arriving in 1609. As soon as the English arrived, they encountered the Powhatan Indians. Archaeologists have discovered evidence that Powhatan women visited the fort and brought food, goods, and supplies to the colonists in the first year of settlement. In 1619 the first “20 and odd” Africans arrived at Jamestown. These first Africans were captured by the Portuguese in Angola in West Central Africa, and sold into slavery. Once in Jamestown, the wealthier merchants and planters bought them for their households. The March 1620 muster of the inhabitants listed 32 Africans in Virginia (17 women and 15 men), with 892 European colonists. Even with the looming threat of warfare with the Indians, these numbers continued to grow, especially as tobacco—a labor-intensive crop—demanded the labor of indentured servants and enslaved Africans.

Throughout the earliest years of European settlement at Jamestown, mortality rates were high. Sickness and disease were a constant threat and plagued the English settlers heavily. Historians have identified both environmental factors and malnutrition as contributing factors to the high death rate among the early colonists. The water around Jamestown Island, where the first colonists settled, is an oligohaline zone, where the mix of fresh and salty water come together to trap contaminates. The resulting water is high in salinity, and also delivered colonists low doses of naturally occurring arsenic, iron, and sulfur. The colonists also inadvertently further contaminated their drinking water with their own waste. The first settlers planned to rely on the local Powhatan Indians for much of their food needs, and so did not plan ahead for their own nutritional needs. A long and devastating drought from 1606-1612 may have contributed to the early colonists’ malnourishment. Even as environmental conditions improved and colonists settled near better water supplies, sickness continued to spread. One colonist wrote home to his parents in 1623 of the pervasiveness of disease in Virginia, “…the nature of the Country is such that it Causeth much sicknes, as the scurvie and the bloody flix, and divers other diseases, wch maketh the bodie very poore, and Weake, and when wee are sicke there is nothing to Comfort us.”

Early Settlement

Soon after their arrival, the first English settlers constructed a fort to defend themselves. The first fort, which was finished on June 5, 1607, included “bulwarkes at every corner, like a halfe moone, and four or five pieces of artillerie mounted in them.” Because the English faced the threat of attack and violence from the Powhatan, they constructed many necessities inside the fort walls, such as a well and a church. Inside the fort, the first settlers also constructed a barracks and other houses. The early colonists constructed these buildings in a style known as “mud and stud,” a traditional building technique that the colonists knew from home in England. When the first men and boys arrived at Jamestown, most of them lived together in the barracks, while after 1611 were built “two fair rows of houses, all of framed timber, two stories, and an upper garret, or corn loft.” The governor of the colony likely lived in one of those row homes.

Eventually, the colonists outgrew the fort, and as more women and families arrived in Virginia the colony expanded. As English colonists expanded outside of James Fort, a small community began to take shape called New Towne, which later grew into “James Cittie.” As the century progressed wealthier colonists used brick to construct their homes in this larger settlement, where wharves, warehouses, and a tavern also appeared to support the growing population. The majority of the colonists continued to live in the more modest frame, not brick, dwellings, with only one or two rooms which served a variety of functions and housed all the family members. Household inventories from later in the 17th century reveal that some families had very little—perhaps just bare necessities for cooking and farming—while other families had tables, beds, chests, chairs, mattresses, and a variety of pots—not necessities, but comforts and luxuries.

Food

Initially, English colonists sought to rely on trade with the Powhatan Indians for corn and meat. The first colonists were also preoccupied with searching for gold, so they did not spend adequate time planting corn or other crops to become self-sufficient without help from the Indians. Colonist George Percy recorded that shortly after their arrival the Indians “(relieved) us with victuals, as Bread, Corne, Fish, and Flesh in great plenty, which was the setting up of our feeble men, otherwise wee had all perished.” Archaeologists have found numerous brass and iron fishhooks at Jamestown, indicating that colonists looked to the river to supplement their diet. Sturgeon became an especially important part of early colonists’ diet. In 1609 Captain John Smith wrote “we had more sturgeon than could be devoured by dog and man.”

Historians sometimes refer to the winter of 1609/10 as “the starving time.” During this period, tensions between the English and the Powhatan escalated. Trade with the Powhatan ceased and the colonists were confined to their fort, unable to hunt. Colonist George Percy wrote that outside the fort, “Indians killed as fast as Famine and Pestilence did within.” Percy also wrote that those colonists who left the fort in search of “serpents and snakes” to eat, were “cut off and slayne” by the Indians. A severe draught which impacted the region from 1606-1612 complicated the situation, with even the Powhatan likely having to compensate for this environmental factor. Desperate colonists resorted to boiling shoe leather and starch before turning to their horses, dogs, cats, and mice. Percy also wrote of survival cannibalism, which has been corroborated by archaeological evidence. Due to the severe feminine and resulting disease, only 60 colonists survived by spring 1610, but ships arriving from England brought supplies.

The following years saw more supply ships arriving from England, bringing pigs, goats, and cattle. In addition to meat the colonists used cows for milk, butter, and cheese, the production of which increased with the immigration of women to Virginia (dairying tasks were traditionally women’s work). Colonists transplanted fruit trees which Captain John Smith noted “prosper(ed) exceedingly.” Fruit like apples and figs could be distilled into hard cider and other alcoholic beverages, which was often safer to drink than the local water supply. Through most of the 17th-century salt was not prevalent in Jamestown, meaning that colonists had few options to preserve meat and fresh fruits and vegetables.

Work and Daily Life

In the early years of the colony, many men and boys spent their days searching for Virginia’s natural resources to benefit England, building her a trading empire to both rival and free the country’s dependence upon Europe. Shirking all other needs such as planting and building projects, John Smith wrote that the colonists were distracted by the prospect of finding gold in Virginia: “There was no talk, no hope, no work but dig gold, wash gold, refine gold, load gold.” In additional to procuring raw materials, the crown had also encouraged the colonists to experiment with industrial pursuits to benefit England, sending skilled craftsmen and laborers to the colony to support that effort. Archaeologists have uncovered evidence of metallurgy (such as testing for gold or other metals) as well as glassmaking, and other colonists tried their hands at silk production with the area’s mulberry trees. None of these ventures proved successful or economically sustainable.

With the colony in disarray after the Starving Time in 1610, officials implemented a set of rules to order the lives of settlers in Jamestown. These “lawes divine, morall and martiall” dictated the colonists’ church attendance (two times every Sunday), ordered housing and bedding to be kept clean, and directed trade and the everyday work lives of both men and women in the colony. Some of the laws (such as the law against doing “the necessities of nature” within a quarter mile of the well) were clearly meant to correct the mistakes of the early years of the colony. Under this code of conduct, colonists were forbidden to gamble, church attendance was mandatory, and blasphemy, treason, robbery, stealing from Indians, and trading without permission were all punishable by death. More minor offenders were whipped in public or endured other physical punishments.

These laws ceased to be enforced after 1619, but by then a new venture had taken hold in Jamestown which ordered the lives of the colonists—planting tobacco. After John Rolfe’s successful experiments with the crop tobacco quickly became the profitable export England was hoping for from the Jamestown venture. Tobacco production, however, was labor intensive. Men, women, and even children contributed to the cultivation of their family’s tobacco crop—clearing fields of trees, planting the tobacco seeds, weeding the crops and “topping” the plants, and removing the tobacco worms that threatened to destroy the crop. Harvesting the leaves to prepare them for export involved even more time and labor.

Threat of Violence and Warfare

European colonists and Powhatan Indians constantly navigated changing relationships, which were sometimes peaceful and sometimes violent. A series of smaller attacks spurned what some historians refer to as First Anglo-Powhatan War in 1609, which lasted through 1614. The colonists’ increasing demands on the Powhatan for food and support reached a climax when colonists attempted to take control of the town of Powhatan (hometown of the paramount chief Powhatan). Shortly thereafter, under the guise of trading for corn Powhatan invited colonists to visit his new capital, but the colonists were ambushed. This attack drove surviving colonists into the safety of James Fort where, without help or food from the Powhatan Indians, they endured the Starving Time. Once food, supplies, and more colonists arrived in 1610, the war picked up in momentum with fighting occurring throughout Virginia. In 1613, the English captured Pocahontas, daughter of the paramount chief Powhatan, and held her for ransom. Pocahontas stayed with the English and, after announcing her intention to marry one of the colonists, John Rolfe, paramount chief Powhatan called off the attacks on English settlements. This peace was short-lived. In March 1622 Opechancanough, younger brother of paramount chief Powhatan, instigated the Second Anglo-Powhatan War with his attack on the dispersed English settlements up and down the James River. The ten year war that ensued devastated both the English and Powhatan, and the sides merely agreed to “a peace” in 1632.

Further Reading

- The Old Dominion in the Seventeenth Century: A Documentary History of Virginia, 1606-1700 By: Warren Billings

- Jamestown, the Truth Revealed By: William M. Kelso

- A Land As God Made It: Jamestown and the Birth of America By: James Horn

- 1619: Jamestown and the Forging of American Democracy By: James Horn