Perhaps none of the punitive acts passed by the British parliament to quell the rebellious activities occurring in the colonies during the buildup to the Revolutionary War were quite as personal as the Quartering Act of 1774. While other acts dealt with taxation, regulation, trade, and the administration of justice, the Quartering Act actually dealt with the disposition of armed British soldiers in the colonies. The Quartering Act specified the conditions for the lodging of British troops in all of colonial North America. However, there are many misconceptions about the Quartering Act.

The Quartering Act of 1774 was not the first British quartering act. With an empire that stretched across the world, the British needed to quarter troops in countries all around the globe. Though many British soldiers had stayed in the American colonies during the French and Indian War (1754-1763), some continued to stay in the colonies following the conflict. Having a standing regular army in colonial cities during peacetime began to lead to resentment and anger among the colonial leaders. While in London, this force was viewed as a necessary evil to help secure the borders of the British North American empire.

In 1765, Parliament passed an amendment to the Mutiny Act, which became known as the Quartering Act of 1765. Contrary to popular belief, this Quartering Act did not direct British soldiers to be billeted in the private homes of the colonists. The 1765 act actually prohibited British soldiers from being quartered in private homes, but it did make the colonial legislatures responsible for paying for and providing for barracks or other accommodations to house British regulars. Other accommodations the colonists could billet British troops in included “inns, livery stables, ale houses” and other public houses.

British soldiers had been housed in New York and other American cities but were generally forced to stay in military barracks. In the city of Boston, the placement of British troops constantly was an issue as the city tried to keep them farther from the center of the city, while the British officers pushed to have them closer among the townsfolk.

Relationships between British soldiers and colonial civilians were often tense and occasionally boiled over into violence, especially in Boston. In the most famous incident, on March 5, 1770, after a few heated exchanges, a group of British soldiers fired into a crowd of Bostonians killing five and wounding six in an event that would be branded as the Boston Massacre.

As tensions continued to grow between the soldiers and civilians, the people of Boston continued to fight back against the British attempts to tax and control them. This culminated in December of 1773 when numerous Bostonians, in an act of defiance, dumped thousands of pounds of British tea into Boston Harbor.

In 1774, following the infamous Boston Tea Party, the British Parliament passed four acts known as the Coercive Acts. The first three acts closed the port of Boston, took away Massachusetts’ ability to self-govern, and removed their ability to administer justice to British soldiers in the colony. The last act passed was the Quartering Act of 1774 which applied not just to Massachusetts, but to all the American colonies, and was only slightly different than the 1765 act. This new act allowed royal governors, rather than colonial legislatures, to find homes and buildings to quarter or house British soldiers. This only further enraged the colonists by having what appeared to be foreign soldiers boarded in American cities and taking away their authority to keep the soldiers distant.

As it had been an ongoing debate in colonial British America, the 1774 act sought to clarify and expand the British ability to quarter troops in American cities. It stated upfront that “doubts have been entertained whether troops can be quartered otherwise than in barracks” and the Royal governor had the right to use “uninhabited houses, outhouses, barns, or other buildings” to quarter soldiers. While “other buildings” could be open to broad interpretation, contrary to popular belief, the 1774 act (like the 1765 act) did not mandate that British soldiers stay in the occupied private homes of American colonists. In fact, it specifically prohibited it.

Regardless, the American colonists were enraged by the Quartering Act along with the other Coercive Acts and they were quickly rebranded “The Intolerable Acts.” The Quartering Act was also especially reviled as it applied not just to rebellious Boston or Massachusetts but to all of the American colonies. Leaders in other colonies began to wonder what other punishments Great Britain may place on them for actions they were not responsible for.

The British troops continued to be quartered in Boston and on April 19, 1775, large scale bloodshed between British regular soldiers and Massachusetts militiamen broke out at the Battles of Lexington and Concord that began the American War for Independence.

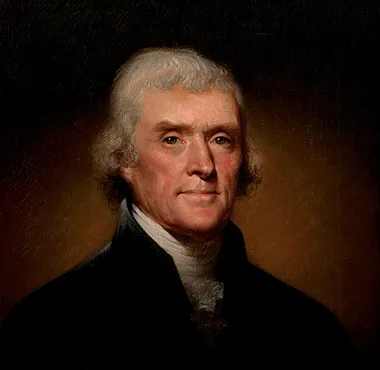

A year later in July of 1776, Thomas Jefferson included the Quartering Act in the Declaration of Independence in a list of the “repeated injuries and usurpations.” Among those grievances against King George III was that he “kept among us, in times of peace, Standing Armies without the Consent of our legislatures” and was “quartering large bodies of armed troops among us.” Though he was not referring to soldiers being stationed inside inhabited private homes, the very presence of armies stationed in American cities during peacetime was a threat to American liberty.

The relationship between armed soldiers and the civilian governments became a central issue of the American Revolution. As the new United States of America formed its own army to defend the former colonies, it became paramount that this military bend to the will of the civilian government to ensure the military could not be used against the people. This was something George Washington would be especially sensitive to and would be sure to defer to civilian authority.

Following the successful conclusion of the Revolutionary War, the issue of continuing to have a standing army during peacetime was fiercely debated. Many anti-Federalists in the early republic era would argue that the United States did not need a standing army during peacetime. As that debate continued in the new United States Congress, the issue of having soldiers stationed in American cities was agreed by all to be unacceptable.

Included in the new Bill of Rights for U.S. Constitution in 1790 was the Third Amendment. This Amendment stated that “No Soldier shall, in time of peace be quartered in any house, without the consent of the Owner, nor in time of war, but in a manner to be prescribed by law.” Though it is often thought today as an irrelevant amendment, at the time following the Revolutionary War, it was considered a usurpation of American liberty to allow soldiers to be quartered among civilian populations and they wanted to ensure that American homes would be protected against the always looming possibility of an armed takeover. Although the British Army was prohibited from being boarded in private inhabited homes in America, the fact that the local government was effectively powerless opened the door to potential abuses of power. The popular narrative that British soldiers forced themselves into the homes of Americans proved to be a true fear of the American people that was addressed as the nation created the new United States Constitution.

Further Readings

- The Long Fuse: How England Lost the American Colonies, 1760-1785 By: Don Cook

- American Revolutions: A Continental History, 1750-1804 By: Alan Taylor

- The Boston Tea Party: A Family History By: Serena Zabin

Related Battles

93

300