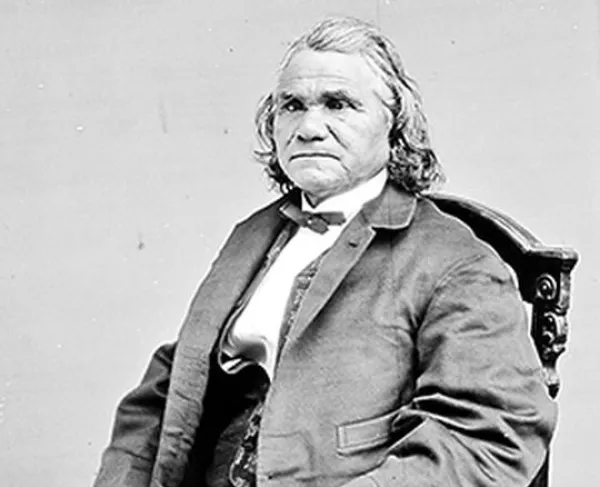

Stand Watie

The only Native American to be fully promoted to the rank of General in the Civil War, Stand Watie was born Degataga, meaning "Stand Firm" in the Cherokee language, and baptized as Isaac in Georgia to a man named David Uwatie and his mixed-race wife, Susan Reese. "Stand Watie" is actually a combination of his English and Cherokee names. Like many children of wealthy Cherokee planter families, Watie grew up bilingual and received a Western-style education from local Christian missionaries. At the time, the Cherokee Nation was considered by many Anglo-Americans as one of the "Five Civilized Nations," along with the Chickasaw, Choctaw, Muscogee and Seminole, for their adoption of certain Western cultural customs such as centralized government, agriculture, Christianity, ability to speak English, as well as the use of African slavery (the Cherokee, of course, had been practicing agriculture for centuries before Europeans arrived in North America, and they were far from the only Native group to do so). This did mean, however, that these tribes had close diplomatic relations with the United States government, and existed as semi-sovereign nations for many years.

Under the threat of Indian Removal and increasing harassment from local state militias, Watie and several other tribal members helped to negotiate the Treaty of New Echota with the United States, which confirmed Cherokee relocation to Indian Territory, now modern-day Oklahoma. Watie's party represented only a minority of the Nation, and their actions caused an enormous rift between them and the majority that opposed any relocation, represented by Principal Chief John Ross. The treaty was ratified in the U.S. Senate, and the Cherokee were ordered to leave their ancestral lands in what became known as the Trail of Tears.

Once settled in Indian Territory, the partisan divides between the Cherokee continued. Watie was actually one of the few treaty party members who was not assassinated in the years between Removal and the Civil War. The issue of slavery and support for the Union or Confederacy also divided the Cherokee along the same lines: John Ross and his allies supported the Union, and included fervent traditionalists who supported abolitionism, while Watie and his fellow planters supported the Confederacy to protect their investment in slaves. Watie joined the Confederate army in 1861, earning a commission as colonel in what became the 1st Cherokee Mounted Rifles. Violence between the two sides caused Ross and many of his supporters to flee to Union-occupied areas in 1862, leaving those that remained to elect Watie as Principal Chief.

Watie spent much of the war in Indian Country, attacking both Union soldiers as well as the Cherokee and other Indian partisans that supported them. He and his men also took part in the battles of Wilson's Creek and Pea Ridge, where they were mainly used as scouts and skirmishers, which remained their general expertise. Watie himself was often noted for his personal valor by many of his peers, and was promoted to Brigadier General in 1864. General Watie was actually the last Confederate commander to cease field operations, surrendering in June of 1865.

After the war, Watie returned to his home in Indian Territory, where John Ross, who the Union had continued to recognize as Principal Chief, ran the nation once again. Fortunately, Ross' successor, Lewis Downing, made a concerted effort to heal the divide that had plagued the nation for so long. As for Watie, he returned to his life as a planter, and used much of his wealth to engage in many other business ventures until his death in 1871. He is buried in Polson's cemetery in Delaware County, Oklahoma.