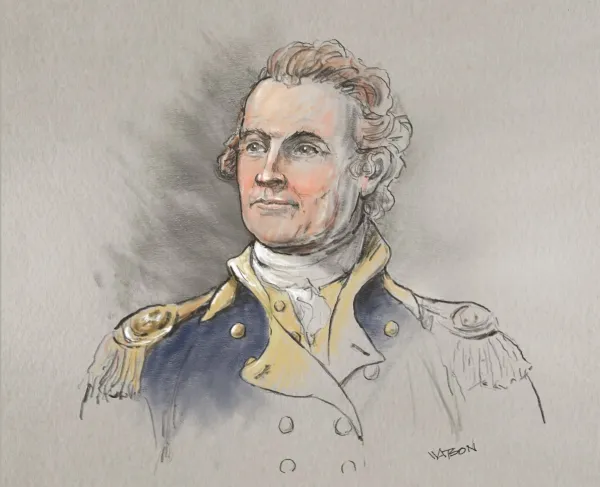

Thomas Mifflin

Thomas Mifflin was born in Philadelphia on January 10, 1744, to a prominent Quaker family. His father, John Mifflin, was a successful merchant who also held several political positions, most notably as a provincial councilor. Mifflin attended the College of Philadelphia, graduating in 1760, and then studied under Judge William Coleman until 1764. Shortly thereafter, he partnered with his brother George to establish a thriving mercantile business. In 1767, Mifflin married his cousin, Sarah Morris. The couple quickly rose to prominence in Philadelphia society, and Mifflin utilized his influence to support the colonial rebellion.

Before his election to the Pennsylvania Assembly in 1772, Mifflin participated in nonimportation meetings in 1769 and 1770, where American colonists protested British policies and asserted their political rights. When the American Revolution commenced in 1775, Mifflin joined the patriot cause by faithfully serving as an aide-de-camp to George Washington. Due to Quaker belief, his military service resulted in his suspension from the meeting. In August 1775, Mifflin was appointed the first Quartermaster in the Continental Army. His most significant military contribution in the Revolutionary War occurred during the Ten Crucial Days. Mifflin led a unit of 1,500 men at Trenton and played a crucial role in preventing their departure despite their enlistments being set to expire following their first battle. Emulating Washington, Mifflin delivered a stirring speech about the American cause and the soldier’s duty. He promised his men they would each receive a ten-dollar bounty and a portion of the plunder from the defeated enemy. At Assunpink Creek, or the Second Battle at Trenton, his reinforcements were essential in holding the Continental position and he attacked Lt. Charles Mawhood's right at a critical moment at Princeton.

Despite this success, Mifflin’s tenure as quartermaster was short lived. Disgusted with the outcome of the Philadelphia Campaign and Washington's perceived lack of leadership, Mifflin left the army in the early winter of 1777. He soon became associated with the Conway Cabal, a group of officers who distrusted Washington and hoped to have him replaced with Maj. Gen. Horatio Gates. However, Mifflin adamantly maintained throughout his life that he was neither involved with this group nor ever had knowledge of their existence.

While Mifflin’s military service is commendable, his true and enduring legacy is rooted in American politics. He served in Congress from 1782 to 1784, including a term as its president in 1783. In this role, he aided in persuading state legislators to send representatives to ensure the ratification of the Treaty of Paris. Additionally, Mifflin participated in the Constitutional Convention and signed the Constitution. Following his time in Federal service, Mifflin continued his political career at the state level, becoming the speaker of the Pennsylvania Assembly from 1785 to 1788 and the President of the Supreme Executive Council from 1788 to 1790. Interestingly, despite holding prominent roles at both the state and federal levels and being known as an influential and skilled orator, Mifflin was notably quiet during the Constitutional Convention. This relative silence at the convention did not directly affect his gubernatorial prospects in 1790. Mifflin was a leading candidate from the start, actively campaigning and ultimately emerging victorious, becoming the first governor of the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania.

Overall, Mifflin’s tenure as governor was successful. He won reelection in 1793 by a substantial margin and ran unopposed in 1796. Mifflin prided himself as a balanced political leader and worked diligently to reform the justice system and reduce the state debt. His term ended in 1799. Although he battled illnesses throughout his time as governor, his condition significantly deteriorated after he left office. Mifflin died on January 20, 1800, in Lancaster, Pennsylvania.

Related Battles

5

905