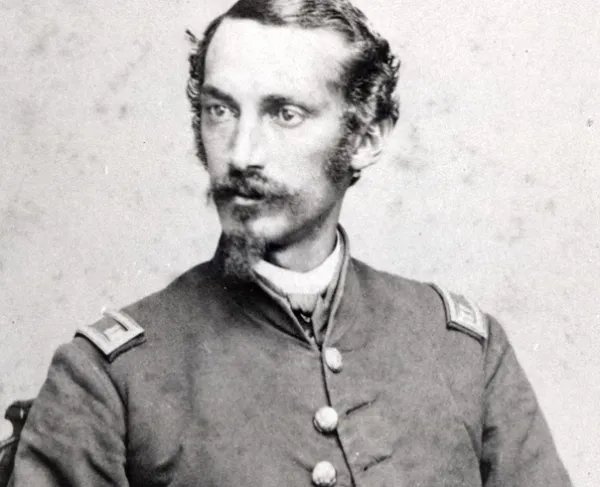

Jedediah Hotchkiss

Jed Hotchkiss was born on November 30, 1828, into a prominent New York family. His great-grandfather founded the town of Windsor and his mother was Lydia Beecher, Harriet Beecher Stowe’s cousin. Hotchkiss was educated at the prestigious Windsor Academy, where he acquired a burning interest in geography and geology. He spent his free time making meticulous observations about the natural world in a pocket journal. He took a special interest in botany and took extra classes at a nearby girls’ school.

After graduation, Hotchkiss spent a year teaching in Pennsylvania and studying the environs of Lyken’s Valley. When the school year finished, he and a friend decided to take an extended walking tour of the Shenandoah Valley of Virginia. During this trip, he was hired by Henry Forrer of the Shenandoah Iron Works as a family tutor. By 1852, Hotchkiss had founded his own school in the Valley, the Mossy Creek Academy, and in 1859 he opened another, Loch Willow.

In his spare time, Jed continued his personal studies in geography and taught himself how to draw maps. A voracious reader of newspapers, he came to believe that secession, an explosive issue at the forefront of the national conversation, would be a mistake for the South.

When states began to break away from the Union in the winter of 1860, Virginia hesitated. It was not until after the Battle of Fort Sumter and President Abraham Lincoln’s call for 75,000 volunteers that Virginians began to truly agitate for self-government. Hotchkiss wrote that “Lincoln’s call for troops to invade and coerce the newborn Confederacy…wrought an immediate change in the current of public opinion in Virginia.”

Students left Loch Willow in droves in order to enlist in the Confederate Army, and Hotchkiss was left with no choice but to close the school. He told his wife that he had “urged resistance, and cannot but use my feeble efforts to resist [as well].” This letter exemplifies his lifelong fascination with the concept of duty and its requirements. To do his duty, Hotchkiss drove a mule team and mapped the regions through which he traveled. He dreamed of being a member of the Confederate Engineer Corps, but he still had no formal training in either subject, especially in comparison to the multitudinous graduates of West Point and other military academies. He was rejected when he sought a position on General Robert Garnett’s staff.

In late June 1861, Hotchkiss was able to find work as a sort of independent contractor making maps for the 25th Virginia Infantry, which was stationed at Rich Mountain, Virginia. He still had no formal connection to the Confederate Army. He wrote to his wife, Sara to explain that “I owe a duty to my country that I must discharge…and at least transmit to our posterity freedom of thought and action….Kiss my babies for me many times. How I want to see their sweet faces. Pa wants them to be good, very good,” and secretly sent her a large portion of his first draw of rations.

On July 11, Union soldiers attacked Rich Mountain. After a day-long fight, the Confederates were nearly surrounded in their camp on the crest. At 1 a.m., the order to retreat was finally issued, but there were no open roads off of the mountain. Hotchkiss would later remember “the rain pouring down in torrents and the night being very dark.”

With no light, trail, or compass to guide him, Hotchkiss stepped into position at the head of a column of 700 soldiers and began to lead them down the mountain. He relied on his instincts and the flow of streams to point the column in the right direction. They made slow but steady progress. At one point, they were challenged by a Union picket, but Hotchkiss repeated the warning whistle that the picket had used, and the Confederates eventually made it off of the mountain without being discovered.

The next day, the men looked to “Professor Hotchkiss” as their de facto leader. When it was discovered that Governor John Letcher was in fact staying at a house not far from the action, Hotchkiss was chosen to deliver a report to him and receive further orders. Even as his star was rising, Hotchkiss wrote to his wife to lament the loss of his engineering equipment and personal effects in the retreat, including the “old blue cloak…that has been my constant companion for 14 years.”

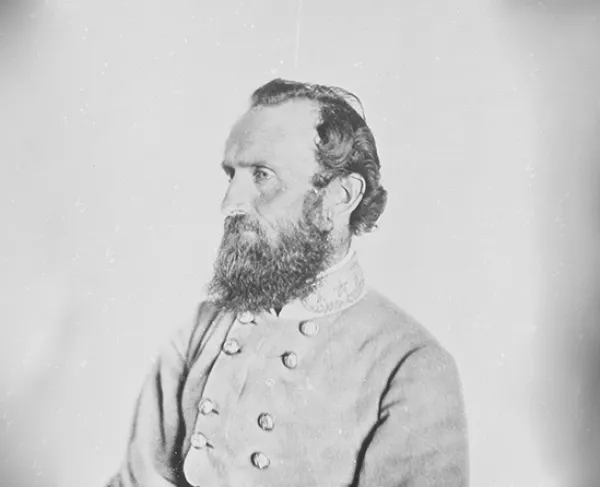

After a brief visit home, in March 1862 Hotchkiss said goodbye to Sara and his two daughters and left once more for the front, this time at the head of a small battalion largely composed of the men he had led off of Rich Mountain. They marched into the Shenandoah Valley to join Stonewall Jackson’s ragtag Army of the Valley.

On March 24, Hotchkiss’s men encountered Jackson’s forces as they were retreating from the Battle of Kernstown. Jackson himself was sitting alone by the side of the road. The gruff Virginian’s first order for the new arrivals was to about face and retrace their steps for several miles. Angry shouts and curses briefly rose from the ranks, but Hotchkiss capably quelled the disturbance. His men went into camp with the rest of the army. Here Hotchkiss received word from Sara that his daughter, Nelly, was near death from scarlet fever. He wrote back to her immediately: “I read, with streaming eyes, by the camp fire…your two letters…may God in mercy have spared my child….I would that I could be with you, but it is forbidden me.”

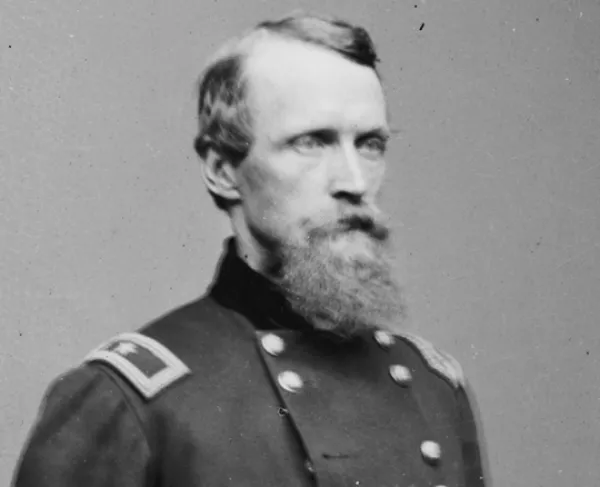

The next day, Hotchkiss was surprised to receive a summons to Jackson’s headquarters. Apparently, Jackson had been impressed by Hotchkiss’s control over the restive soldiers and had inquired as to why a civilian would hold such authority over military men. Impressed by tales from Rich Mountain, Jackson told Hotchkiss: “I want you to make me a map of the Valley, from Harpers Ferry to Lexington, showing all the points of offense and defense in those places.” Hotchkiss finally had a staff appointment and, as he put it, “a big job.” Jackson’s staff was exceptional among general staffs: three present or future doctors of divinity, eleven holders of masters degrees or higher, four attorneys, and nine educators; and hardly any of them older than 30.

Still worried about Nelly’s condition, Hotchkiss threw himself into his work and almost immediately proved his worth to Jackson by providing detailed maps of the territory around the army camp. In his first report to the general, Hotchkiss identified several previously unknown weaknesses of their current position, compelling Jackson to relocate the army that very afternoon.

Several days later, Hotchkiss received a letter from Sara. Nelly had recovered. She had even enclosed a single violet petal as a gift for her father. He wrote back: “Pa would like to sit out on the porch with the little girls and Ma and hear [the birds] sing rather than be where he has to…hear so much of men killing and being killed….but our rights we must have cost what it may.”

Hotchkiss spent the next several months serving as a staff officer and composing the map of the Valley, which would end up being more than eight feet long when fully unrolled. Jackson’s army was meanwhile engaged in a desperate campaign to defend the Shenandoah Valley from multiple Union armies.

Jackson would often ask Hotchkiss to lead columns to their objectives, including during combat situations. Hotchkiss’s knowledge of the Valley and its denizens proved helpful many times. In May, the Confederates passed near Mossy Creek, the site of his first school, and Hotchkiss was able to call on his old neighbors to lend their wagons to build an impromptu bridge over the swollen waterway. By the end of June, Jackson’s army had defeated forces more than three times their number and had temporarily neutralized the Federal threat in the Shenandoah Valley.

Hotchkiss continued to serve on Jackson’s staff until the general’s death in 1863. His cartography continued to aid Jackson’s strategic planning. At the Battle of Chancellorsville, it was Hotchkiss who discovered the route for Jackson’s dramatic flank attack. After Jackson’s mortal wounding (which Hotchkiss witnessed) and death, Hotchkiss continued as a topographical engineer with the Confederate forces, frequently working personally for General Robert E. Lee. He was nearly killed when a bullet smashed his binoculars at the Battle of the Wilderness.

In the late summer of 1864, Hotchkiss returned to the Shenandoah Valley in the service of General Jubal Early, who was making a last-ditch effort to invade the North and draw Union armies away from Richmond. Hotchkiss was shot in the hand during the campaign. Although Early’s offensive ended in strategic failure, Hotchkiss continued to augment the Confederate efforts with his map-making. One such map enabled the surprise Confederate assault at Cedar Creek in October 1864. He served until General Lee surrendered at Appomattox.

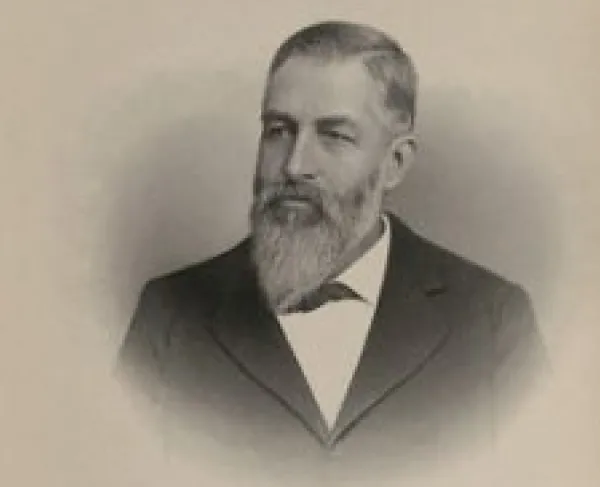

After the war ended in 1865, Hotchkiss opened an engineering firm and taught school in Staunton, Virginia. In 1867, he wrote a book with a friend, Jackson's former chief of ordnance William Allen, entitled The Battlefields of Virginia: Chancellorsville. He published a number of scientific articles about the flora and fauna of Virginia. Hotchkiss died in January 1899 after a successful postwar career as a geologist and engineer.

Related Battles

17,304

13,460