On the War Path

In the first week of May 1864, the Federal army launched two offensives designed to end the Civil War as quickly as possible. General-in-chief Ulysses S. Grant had long been frustrated that Union forces in Virginia had made scant headway against Confederate Gen. Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia. He also was aware that Lee had shifted two divisions of his army west to help Gen. Braxton Bragg’s Army of Tennessee win a smashing victory at Chickamauga the previous September. That victory had derailed the Union offensive along the railroad linking Louisville, Ky., with Nashville and Chattanooga, Tenn. Grant had been called on to salvage the situation by engineering a victory at the Battle of Chattanooga in late November, lifting the semi-siege of the Army of the Cumberland in that city.

Grant’s elevation to supreme command of all United States forces in March 1864 allowed him the chance to do something about coordinating moves between the War’s east and west theaters. Bending to Lincoln’s wishes, he made his headquarters in Virginia to direct operations against Lee. On Grant’s recommendation, Maj. Gen. William T. Sherman took charge of operations in the West.

Grant gave Sherman only general directions for the spring offensive. Sherman could count on one of the largest concentrations of Union strength ever assembled in the West: 100,000 men divided into three forces, Maj. Gens. George H. Thomas’s Army of the Cumberland, James B. McPherson’s Army of the Tennessee and John M. Schofield’s Army of the Ohio.

Sherman, a master logistician, worked very hard to strengthen his supply line before setting out for Atlanta. He commandeered locomotives and cars from Northern railroad companies, constructed blockhouses at railroad bridges and placed garrisons at key locations along the single-tracked line between Louisville and Chattanooga. The railroad would barely support his army with essentials during the Atlanta Campaign.

The Confederate Army of Tennessee, now commanded by Gen. Joseph E. Johnston, dramatically improved in spirits and effectiveness during the winter months of 1864. With the addition of Lt. Gen. Leonidas Polk’s Army of Mississippi in mid-May, the Army of Tennessee boasted nearly 65,000 troops.

Sherman began his drive toward Atlanta when Grant began his own offensive against Lee — the first week of May 1864. Sherman’s first obstacle was Rocky Face Ridge, a high, steep feature common to the Appalachian Highlands. Its rugged profile defied attack. Sherman positioned troops to confront Johnston and sought means to flank the Confederates out of their stronghold. Union forces gained control of Snake Creek Gap several miles south of Johnston’s line and compelled the enemy to evacuate the area around Dalton on May 12. Both armies lost fewer than 1,000 men at Rocky Face Ridge.

Johnston retired to Resaca to protect his rail link with the Confederacy. Here, on May 14–15, Sherman launched several attacks on the Confederates. Johnston’s army had taken position on the irregular high ground north of the Oostanaula River. His men had little experience at digging fortifications and inexpertly dug their fieldworks, resulting in needless casualties, even as they repelled every Union assault.

Sherman had planted a pontoon bridge downstream from Resaca and this compelled Johnston to evacuate the town on the evening of May 15. Losses at Resaca had been significant, amounting to nearly 3,000 men on each side.

Johnston could find no suitable ground for a defensive stand for many miles south of Resaca. He finally landed at Cassville, more than 40 miles from Dalton, on May 19. Here, a high ridge east of town offered a good position, but Johnston first took the offensive against his opponent. The Federals approached in two columns, and Johnston hoped to strike one before the other could interfere. But corps commander Lt. Gen. John Bell Hood, responsible for making the attack, reported unexpected Union troops to his flank and called off the assault. Johnston had to accept the decision and fall back to the high ridge. When the Federals closed up to this ground and opened flanking artillery fire, Hood and Polk implored Johnston to retreat and he caved to their views, pulling out of Cassville and across the Etowah River on the night of May 19.

Sherman’s progress thus far had been facilitated by the topography of northwest Georgia. North of the Etowah, the terrain was typical of Appalachia — high continuous ridges that could hide Union flanking moves. South of the Etowah, however, Sherman left the Appalachian Highlands and entered the Piedmont region of Georgia, its rolling terrain often covered with dense forests.

Sherman plunged into this region by crossing the Etowah River on May 23, temporarily cutting away from the railroad in order to swing around the Allatoona Hills. He relied on wagon trains to supply his men. Although Sherman hoped to reach Marietta or even the Chattahoochee River in one movement, Johnston became aware of the move and shifted his army to block him.

For the next two weeks, Sherman’s men floundered in a wasteland. Three small but sharp battles took place at New Hope Church, where Maj. Gen. Joseph Hooker’s XX Corps attacked a division of Hood’s Corps on May 25; at Pickett’s Mill, where a division of Maj. Gen. Oliver Otis Howard’s IV Corps attacked Maj. Gen. Patrick Cleburne’s division of Lt. Gen. William J. Hardee’s Corps on May 27; and at Dallas, where McPherson’s men repulsed a poorly planned attack by Maj. Gen. William Bate’s Division of Hardee’s Corps on May 28.

By June 7, after days of constant skirmishing between the heavily fortified lines, Sherman shifted back to the railroad. Johnston then evacuated his New Hope Church, Pickett’s Mill and Dallas Line. Both sides suffered up to 2,500 losses in this phase of the campaign.

The Confederates fell back to the Mountain Line, bolstered by high, dominating peaks, such as Lost Mountain on the left and Pine Mountain in the center, as well as the lower Brush Mountain on the right. Johnston’s strategy was to fortify every possible position in Sherman’s path while conserving his own manpower.

Sherman’s only recourse was to approach these positions and try to flank them or threaten vulnerable sections of the Confederate line. That is why Johnston evacuated Pine Mountain on the night of June 14 — it jutted ahead of the rest of his line. A lucky shot from a Union artillery piece killed Polk that day only hours before the evacuation. A portion of the Confederate army fell back to create the Gilgal Church Line, but the salient at Gilgal Church also became a vulnerable spot. So on the night of June 16, the Confederates evacuated the area around Gilgal Church to form the Mud Creek Line. Here, a sharp angle in the Rebel position near the Latimer House proved untenable because of enfilading Union artillery fire. Johnston evacuated the Mud Creek Line on the night of June 18 and took a position on the Kennesaw Mountain Line. Anchored by the twin peaks of this imposing mountain, the Confederates held their strongest position yet in the Atlanta Campaign.

Sherman was stymied here for two weeks as the weather deteriorated, pouring showers on his exposed troops nearly every day. Sickness rose in Johnston’s ranks, while the dirt roads turned into rivers of mud and impeded Sherman’s flanking movements. After nearly two months of continuous contact with the enemy, exhaustion also exacted its toll on the men in both blue and gray.

By late June, the tenor of the campaign and how it compared with Grant’s operations in Virginia had become clear. The nation was stunned by the ferocity and dogged determination of Grant’s Overland Campaign toward Richmond. In massive battles at the Wilderness, Spotsylvania and Cold Harbor, as well as the first Union offensive at Petersburg, Grant’s succession of attacks had racked up approximately 65,000 losses by mid-June. “Grant’s Battles in Virginia are fearful but necessary,” Sherman told his wife. But he added that in Georgia, “[w]e cannot afford the losses of such terrible assaults as Grant has made.” Perched at the end of a tenuous rail line, Sherman had to rely on maneuver mixed with limited assaults to achieve his aims. But he was growing desperate by the time he landed at Kennesaw. The weather, terrain, and Rebel earthworks had stalled his advance; he feared Johnston might detach troops to help Lee.

Thus Sherman was willing to try a major assault on well-prepared fieldworks. On June 27, 15,000 Federal troops attacked three points along the Kennesaw Line. They were repulsed at all three points and lost 3,000 men, even as Johnston suffered less than 1,000 casualties. Only at Cheatham’s Hill did the Federals remain close to their objective and dig in a few yards from the Confederates.

The weather improved soon after the failed assault, allowing Sherman to break most of his command from the railroad and move south to flank the Confederate left. The mere start of this movement led Johnston to evacuate the Kennesaw Mountain Line on the night of July 2. He fell back only a short distance to Smyrna Station, where engineers had already staked out new fieldworks. After holding there for two days, the Confederates evacuated on the night of July 4 and fell back to the Chattahoochee River Line, a strong position along high ground just north of the last natural barrier to Sherman’s advance. The Confederates evacuated this line on the night of July 9, only hours after Sherman secured crossings of the Chattahoochee River upstream and downstream from their position.

In two months of digging and retiring, Johnston allowed the Federals to advance 100 miles, until they were only 10 miles from Atlanta. While Sherman had suffered more than 15,000 losses, he partially made them up with the addition of the XVII Corps of McPherson’s army in mid-June. More important, the casualties had not impaired Sherman’s ability to continue the drive. Johnston, similarly, had lost about 9,000 men without impairing the Army of Tennessee’s ability to resist.

But the political consequences of this retreat were enormous. Jefferson Davis anguished at the thought of giving up so much territory without a general battle. While Lee fought doggedly, Johnston seemed willing to give up ground and, Davis feared, Atlanta as well. When Davis pointedly asked Johnston to detail plans for defense of the city, the general could not satisfy the president. Davis relieved him of command in favor of John Bell Hood on July 17.

Davis’s decision was pivotal in shaping the campaign. Hood had a sterling record as a division commander in Lee’s army, but he had lost the use of one arm at Gettysburg and had suffered the amputation of a leg at Chickamauga. Still, Hood exuded an aggressive attitude. Although surprised by the appointment, he tried his best when assuming command.

Hood felt compelled to take the offensive. Atlanta was too well protected by a ring of earthworks to risk an assault, so Sherman planned to cut the railroads that fed Hood’s army in the city. The Federals started their move by crossing the Chattahoochee River on July 17. As Thomas’s Army of the Cumberland approached Atlanta from the north, Schofield’s Army of the Ohio and McPherson’s Army of the Tennessee headed for Decatur, a stop on the Georgia Railroad east of Atlanta.

Hood attacked Thomas as the Federals crossed Peachtree Creek a short distance north of Atlanta on the afternoon of July 20. Hastily prepared, launched later than planned and poorly executed, the Rebel assault took the Yankees by surprise but failed in its primary objective. Brig. Gen. John Newton’s division of the IV Corps and Hooker’s XX Corps repulsed the Confederates and inflicted 2,500 losses while suffering only 1,900 casualties.

Hood immediately planned a second strike, this time against McPherson’s army. As Schofield and McPherson moved west from Decatur, tearing up the Georgia Railroad, they took position east of the city. McPherson neglected to adequately protect the left of his line, so Hood moved Hardee’s Corps on a long flanking march during the night of July 21 to hit the exposed flank. Hardee slammed into McPherson’s left at noon on July 22 and nearly crushed the Army of the Tennessee. Uncoordinated lunges by Confederate brigades and determined resistance by the Federals (many of whom jumped from one side of their earthworks to the other as needed to meet attacks coming from three directions), saved the Union army. Hood’s Corps, temporarily under Maj. Gen. Benjamin F. Cheatham, attacked McPherson’s front and briefly held a battery and a section of the trench until Union counterattacks drove it away. McPherson was shot by Confederate skirmishers early in the fight, but Maj. Gen. John A. Logan took charge and brought the Federals to victory. The bloody Battle of Atlanta, also known as the battle of July 22, resulted in 3,722 Union casualties and 8,500 Confederate losses.

Sherman did not rest. Naming Howard to replace McPherson, he shifted the Army of the Tennessee to the west of Atlanta in an attempt to seize the last railroad that entered the city from the south. Lt. Gen. Stephen D. Lee arrived at Atlanta in time to take permanent command of Hood’s Corps and led the effort to counter this move. As the Federals neared Ezra Church, due west of Atlanta, Hood wanted Lee to block their advance so Lt. Gen. Alexander P. Stewart’s Corps (Polk’s old Army of Mississippi), could use the Lick Skillet Road to attack the Federal flank. Reaching the area on July 28, Lee believed Federal skirmishers already controlled the road. He decided to attack. For five hours, the Confederates crossed a shallow valley into the teeth of heavy musketry until 3,000 of them were shot down. Although the Federals barely held on to their position, they miraculously suffered only 632 casualties.

After a week and a half in command, Hood had fought three major battles and lost more than 11,000 men. At best, his efforts had eliminated 6,300 Union troops and merely delayed Sherman’s strategy. Many Confederates regretted the loss of Johnston and began to fear that Hood would use up the army.

Yet, Sherman’s effort to reach the Macon and Western Railroad south of Atlanta stalled every time he shifted troops between July 29 and August 26. Now acting strictly on the defensive, Hood constructed a new line of earthworks linking Atlanta with East Point several miles south. East Point was the junction of rail lines from Columbus and Macon on which Hood relied. His East Point Line prevented Sherman from reaching the tracks.

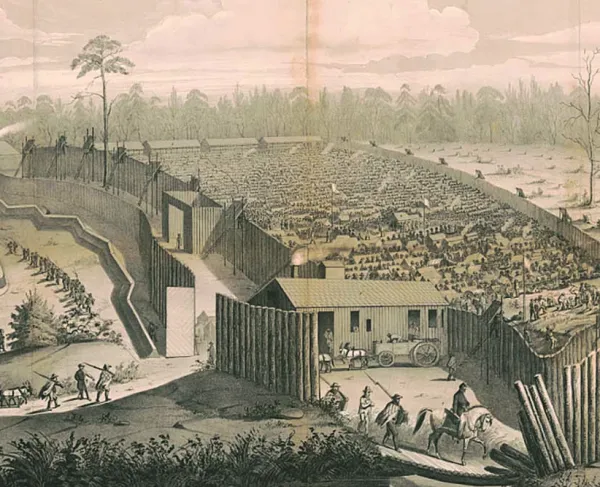

During the last month of the Atlanta Campaign, both armies dug extensive, deep and well-protected earthworks within a few hundred yards of each other, stretching from northeast of the city to the southwest of Atlanta. Here they sniped, skirmished and bombarded each other, until the operations resembled aspects of a siege. Lice became prevalent in the trenches, which filled with water and mud when it rained and dried out to a hardness resembling concrete in dry weather. The Federals normally dominated the skirmishing that increased in places until it amounted to a small battle. Sherman brought down heavy artillery from Chattanooga to bombard Atlanta, burning buildings and killing a number of civilians.

This “siege” of Atlanta ended by late August. First, Hood gambled on sending his cavalry force to tear up Sherman’s railroad. Joseph Wheeler hit the tracks between Atlanta and Chattanooga, but was unable to do much damage before he was chased away. Sherman had tried the same tactic in late July, sending most of his available cavalry to disrupt Hood’s rail network with no success.

The only recourse was to take his infantry south to do that job. The Federals evacuated their trenches on the night of August 26. While the XX Corps fell back to protect the railroad crossing of the Chattahoochee River, the other six corps in Sherman’s army marched south, temporarily cutting away from the railroad. For several days, Hood did not know where they went, until reports surfaced that Union troops were tearing up the railroad a few miles southwest of East Point. Hood shifted Hardee and Lee to Jonesborough to protect the other (and last) rail line supporting his army.

Sherman arrived at Jonesborough just after the Confederates. Taking position within artillery range of the railroad depot, the Federals dug in. Hardee attacked on August 31. The assault was uncoordinated, lacked vigor and utterly failed. That night, Hood received word of more Union troops capturing sections of the railroad between Jonesborough and East Point. He ordered Lee to shift his corps northward to deal with this problem.

That left Hardee alone to confront Sherman at Jonesborough. On September 1, the Federals attacked, captured a section of the Confederate trench and compelled Hardee to evacuate Jonesborough that night. Hood had no recourse but to order the evacuation of Atlanta as well. Early on the morning of September 2, troops from the Union XX Corps entered Atlanta and accepted the city’s surrender.

Hood managed to save his army by maneuvering Stewart, Lee and Hardee to Lovejoy’s Station several miles south of Jonesborough. Sherman advanced to Lovejoy’s and skirmished for several days, but then broke contact and retired to Atlanta. Hood moved his army to Palmetto Station more than 20 miles southwest of the city.

The Atlanta Campaign finally ended after four months of nearly continuous contact involving up to 165,000 soldiers in blue and gray. Total casualties amounted to 27,500 Federals and 21,500 Confederates. Sherman’s victory may have boosted Abraham Lincoln’s flagging political prospects in the face of the upcoming presidential election that fall.

The Atlanta Campaign demonstrated Sherman’s mastery of the operational art. He applied continuous pressure on his enemy for four months, while maintaining the combat effectiveness of his large army — an accomplishment unprecedented in American history. In contrast, the Army of Tennessee had been worn down physically and emotionally by the draining campaign. It had exchanged its most beloved commander for a man many soldiers distrusted. And northwest Georgia had been devastated by the sweep of both armies across the land. The countryside was shorn of much of its food and animals, a catastrophe that could only be healed by time and peace.

Your gift today helps save 77 acres at Ringgold Gap, Rocky Face Ridge, and Kennesaw Mountain — where history was made — with an incredible $22-to-$1...

Related Battles

837

600

2,747

2,800

3,000

1,000