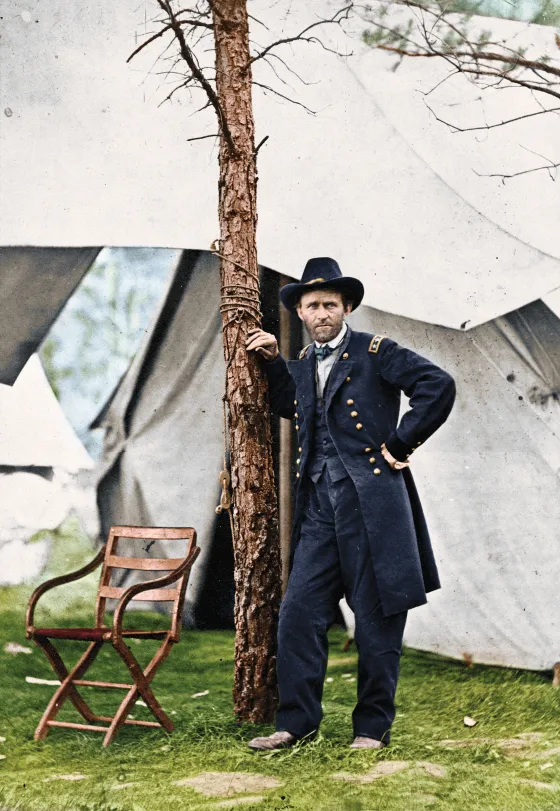

Cold Harbor. Two words that conjure images of brutality and futility. Out of 13 days of fighting, it is one charge on one day that came to characterize the memory of Ulysses Grant’s generalship and cling to him, like a leech, all the way to the highest office in the land —the presidency.

Cigar clenched between his teeth, flies buzzing about him as he watched the still-smoldering campfire, a middle-age man with a scrubby beard and tanned face, his uniform stained with sweat and grime stands in front of his tent. Ulysses Simpson Grant — "U.S." to the media, but jokingly, "Sam" to his friends — peered into the horizon. In his immediate view sprawled the powerful Union Army of the Potomac, with an independent corps, the XVIII, borrowed from the Army of the James, attached to the command. Beyond his line of sight, behind immense earthworks, lay his antagonist, the formidable Confederate Army of Northern Virginia under Gen. Robert Edward Lee.

In the first days of May 1864, now a month prior, the Civil War's two principal armies had locked horns in battle west of Fredericksburg, Va., in a second-growth forest simply called the Wilderness. Since that first encounter, which resulted in two days of bloodletting in the tangled growth, Grant had initiated a campaign of forward movement, sidestepping around Lee's right flank. His first destination was the pivotal crossroads at Spotsylvania Court House. Lee beat him to the area, however, and erected extensive earthworks. On May 12, Grant unleashed the Union H Corps against a salient in the Confederate lines initially dubbed the "Mule Shoe," but after more than 18 hours of intense combat, now known to history as the "bloody Angle."

But the Ohioan was not foiled. After further contemplation and probing, Grant again headed south, around Lee's right flank toward the North Anna River. When stymied there, Grant sidestepped again. A month into the campaign, his forces depleted by some 50,000 cumulative casualties, Grant stood on the banks of the Pamunkey River. From the Union lines, one could practically see the spires of the churches of Richmond, the Confederate capital, with a field glass.

The battle now joined on the Tidewater Peninsula, near the location of the Seven Days' Campaign approximately two years earlier, has come to greatly shape the memory of Grant's military career.

Fighting at Cold Harbor lasted 13 days, yet one charge on one day is sometimes used as a summation of Grant's entire career, a process solidified by the memoir, penned near the end of his life: "I have always regretted that the very last assault at Cold Harbor was ever made," he wrote, "No advantage whatever was gained to compensate for the heavy loss we sustained."

For this attack, Grant became known as The Butcher. His own former staff officer, Horace Porter, did not help the cause when he wrote, some 30 years later, the following sensational story:

"As I came near one of the regiments which was making preparations for the next morning’s assault, I noticed that many of the soldiers had taken off their coats, and seemed to be engaged in sewing up rents in them. The exhibition of tailoring seemed rather peculiar at such a moment, but upon closer examination it was found that the men were calmly writing their names and home addresses on slips of paper, and pinning them on the backs of their coats, so that their dead bodies might be recognized upon the field, and their fate known to their families at home.”

Both armies were well entrenched by June 3, 1864, having spent the previous several days building elaborate earthworks. Historians have debated what prompted Grant to launch the frontal assault that morning. Whatever the reasoning, at approximately 4:30 a.m., with a light rain falling, the blue-clad infantry scrambled out of their earthworks and entered the open field. Even with the precipitation, from the Confederate line burst forth thousands of rifles belching flame and shot. Bullets found bodies, limbs were shattered, men fell, dead and dying.

The living tried moving forward, some turning sideways, like a pedestrian braving a pelting rainstorm. But, instead of water drops, these were lead missiles. More men fell. Some of the Union infantry found temporary lodgments in the Confederate lines. The 7th New York Heavy Artillery, converted artillerymen now serving as infantry, found a ravine and was able to break through a portion of Col. George Patton's Brigade of Virginians. A rush of Floridians and Marylanders helped seal the gap and push the federals back.

By midday, the attacks had stalled. Orders from Maj. Gen. George Meade, the commander of the Army of the Potomac, went out to resume the assaults across the entire front of the army. Yet, his various corps commanders — Maj. Gens. Winfield Hancock of the II Corps, Gouverneur Warren of the V Corps and the commander of the contingent from the Army of the James, William Smith of the XVIII Corps — all advised against it. The hard-lucked Maj. Gen. Ambrose Burnside, leading the IX Corps into what he mistakenly thought was the Confederate main line but in actuality were only skirmishers' rifle pits, became bogged down, although his troops continued to sporadically fire on the enemy throughout the remainder of the day.

How many men fell wearing Union blue that day? A cursory glance at any online article or some generalized reading will put the number of Union dead at approximately 7,000. Recent scholarship, however, has brought that number down to closer to 4,000. Still a significant, even horrific, number for a single assault. However, let's put it into perspective.

Approximately a year earlier, in July 1863, Lee launched a massive assault against Union forces near a small hamlet in southeastern Pennsylvania. That assault, labeled "Pickett's Charge," cost Lee's forces approximately 6,000 men. Yet, that charge has been romanticized and remembered more favorably, and is part of the lore of the fallen Confederacy. Meanwhile, Grant's assault gave him the moniker "The Butcher."

Delving even further, Grant had also launched a massive assault against a protruding salient at Spotsylvania Court House. That one broke the Confederate line, ushered in 18 hours of fierce hand-to-hand combat and almost resulted in breaking Lee's army in half. Grant is not remembered as a butcher for that action.

A "butcher" does not have strategic vision and would continue to batter his head against an entrenched enemy, continue to throw men recklessly against his position. Grant, however, did have a vision: destroy Lee's army. And if Cold Harbor did not offer that opportunity, then another place of his choosing would.

Just as he did after the Battle of the Wilderness, after the Battle of Spotsylvania Court House and now after the Battle of Cold Harbor, Grant resorted to his forte: turning Lee's right flank. This time, he moved across the James River toward the important transportation hub at Petersburg.

Grant did indeed have an objective, and he would not deviate. This self-assuredness, confidence and demeanor had won the trust and respect of President Abraham Lincoln. When the Ohioan became general in chief of all Union armies, the president deviated from his previous routine of demanding plans for action against the Confederates, instead remarking: "The particulars of your plan I neither know or seek to know. You are vigilant and self-reliant; and, pleased with this, I wish not to obtrude any restraints or constraints upon you.”

Even Grant's nemesis, Lee, realized that, once Grant reached the James River, it was just a matter of time for the Confederacy. With the Union army poised at that waterway, it would force the Confederates to defend the capital of Richmond and the link to the rest of the Confederacy: Petersburg.

Grant had a superstition of never turning back. According to Porter, "[Grant] would try all sorts of cross-cuts, ford streams, and jump any number of fences to reach another road rather than go back and take a fresh start.”

Thus, as Grant chomped on a half-lit cigar and swatted flies that swarmed around his command tent, he had a vision for the future. Would he come to regret Cold Harbor? Yes, in part. But, every military leader has some regretful decision. Grant had the acumen though to try, to endeavor to finish the job, and a tenacity to hold on until the job was done. He would need these personal attributes to finish the job against the Confederacy and move into his post-war career, transitioning from the military to politics.

Yet the stain of that charge at Cold Harbor would continue to follow Grant the rest of his days. The power of memory would continue to tug the focus of Grant's military image and connect a part of that legacy to that one instance on that one field in Virginia.

Preserve 838 acres at Gaines’ Mill, Cold Harbor and White Oak Road — land where the nation’s future was decided. Help raise $431,350 to protect this...

Related Battles

12,737

4,595