Emanuel Leutze's "Washington Crossing the Delaware" depicts the crossing of Washington's army just prior to the attack on the Hessians at Trenton on December 26, 1776. The man standing next to Washington holding the flag is Lieutenant James Monroe, future President of the United States, and the man leaning over the side is General Nathanael Greene.

By December 25, 1776, the war for American independence had lost its early optimism and glamour, and was on the verge of dissolving after the defeats suffered by its shrinking Continental Army during the New York Campaign and in its retreat across New Jersey and the Delaware River into Pennsylvania. The next 10 days, however, prevented the collapse of the war effort and provided the renewed momentum that ultimately led to victory.

When writing about those crucial days, one of Washington's generals praised Washington for demonstrating the ability to deceive the enemy by giving "an appearance of something which is not intended, while under this mask some important object is secured;' while avoiding "those wily snares which are laid for him.' Before December 25, 1776, Washington's personal bravery was unquestioned, but it was not until this campaign that some would argue that he revealed his skills at deception, along with his audacious and decisive character. During this campaign Washington demonstrated his talents to react to changing situations, complete intelligence gathering, and use of terrain and understanding of his enemy to achieve victory. He restored confidence and spirit in the American cause, and himself as commander during this campaign.

Two or three days after the Continental Army crossed into Pennsylvania in the first week of December, General Hugh Mercer's 18-year-old aide-de-camp, Major John Armstrong, overheard several meetings between Adjutant General Joseph Reed and Mercer discussing the possibility of attacking some or all of the British cantonments that General William Howe had spread across New Jersey. These cantonments were meant to support and encourage the Loyalists and to provide a base for eventually taking Philadelphia. The two men agreed to bring up the subject with Washington and other officers. Washington welcomed the resulting conversations and, between December 8 and 25, gathered intelligence and pondered how to drive the British from some portion of their cantonments with his small army, regaining at least part of New Jersey.

While Washington developed his plan, small detachments crossed the Delaware River daily to gain information and harass Hessian outposts and patrols. These frequent hit-and-run attacks wore out the hired Hessian auxiliaries physically, and deceived British leaders into believing that Washington's army was incapable of mounting a major attack.

Washington knew that his army, while small, was larger than any one of the cantonment garrisons, encouraging him to "attempt a stroke upon the forces of the enemy, who lay a good deal scattered:' This urge to attack was tempered by the reality that he badly needed reinforcements and, worse, that the enlistments of a large portion of his troops ended on December 31. However, Washington firmly believed that he needed to attack the enemy troops in New Jersey in order to revitalize the Whigs and the dispersed state government, subdue rising Loyalist confidence, and encourage reenlistment in the Continental Army.

By December 14, Washington was clearly working through various options, writing to several generals that "I should hope we may effect something of importance." During conversations with various officers and while analyzing multiple intelligence reports, Washington developed a plan to drive the British from as much of New Jersey as possible. He would start with a surprise attack on Trenton, but he knew that victory would only be symbolic if not followed up with additional actions.

Washington's plan for attacking Trenton has been described as extremely complex and fraught with dangers that could easily have led to defeat. Washington's password for the day, "Victory or Death," demonstrated his awareness that failure could mean the end of the Revolution. He knew the attack must be unexpected, quick and decisive, and avoid laying siege to the town or becoming involved in a drawn-out battle — lest the British troops at Bordentown and Princeton quickly reinforce the Hessians at Trenton and pin the Americans against the river. He planned to quickly capture the entire Trenton garrison, remove the prisoners to Pennsylvania and then combine his forces for further attacks on other British cantonments.

Washington planned to cross three military forces into New Jersey on the night of December 25. Although only the one group he personally led was able to cross in the horrible weather and river conditions, he succeeded in capturing most of the Hessians at Trenton and putting those stationed south of Trenton into panic, causing them to seek protection in Princeton. While Washington could not make further attacks on December 26, he instead crossed his army back to Pennsylvania. He knew that additional action was expected of him. The Continental Congress wrote to Colonel Thomas Fleming of the 9th Virginia Regiment, overdue on its march to join the army, informing him that Washington had made "an unexpected stroke at Trentown where he now reigns master. We hope to drive the enemy out of New Jersey and if you haste up you'll come in for a share of the glory." On December 28, Washington told Congress that he wanted all available troops to be ready to join up with him to create "a fair opportunity ... of driving the enemy entirely from, or at least to, the extremity of the province of Jersey." Congress also felt that keeping the troops on the offensive "clearing the Jerseys" would encourage reenlistment, whereas acting defensively would discourage it.

Washington crossed his troops back to New Jersey between December 27 and 31, posting his main force at Trenton and other forces south of town in the Bordentown and Crosswicks areas. Some doubted his wisdom, believing he was inviting defeat by re-occupying Trenton. Major James Wilkinson worried that Washington had placed himself in a dangerous situation, putting himself "into a 'cul de sac,'" with the river at his back. He also had "a corps numerically inferior to that of the enemy in his front," an enemy that until recently had forced him to retreat. Washington continued to gather intelligence, especially about the British at Princeton. During this crucial time, Washington was able to convince about half of the men whose enlistments expired on December 31 to extend them for six weeks. He told them, "If you will consent to stay only one month longer, you will render that service to the cause of liberty, and to your country, which you probably never can do under any other circumstances. The present is emphatically the crisis, which is to decide our destiny."

Washington was not planning to sacrifice his men in a major defeat at Trenton, and it is likely that he already planned to make Cornwallis believe he would make a stand at Trenton. Instead, he would secretly march overnight to Princeton, defeat any rearguard there and continue on to Brunswick to capture the British supplies and war chest located there. Washington no doubt had multiple conversations with people who knew the area well and were aware of a new, little-used road that still had low tree stumps in it. Washington was also shown on a spy map, that he could use to skirt the British troops at Trenton and reach Princeton undetected. For this plan to work, Washington needed everyone, especially British spies, to believe he meant to make an all-or-nothing stand at Trenton.

Preparing for the anticipated British advance from Princeton, Washington ordered up his troops from the Bordentown area to Trenton and posted units at locations on the main road from Princeton with orders to slow the British advance and prevent their reaching town before evening. He did not make the mistake that the German colonel, Johann Rall, had made by trying to defend the town, but rather formed up his troops on the hill on the southeast side of Assunpink Creek, making it appear that his only chance was to delay and punish the British for as long as he could and make them pay a heavy price when attacking him; that is, make it another Bunker Hill.

The long day of successful delaying actions on January 2 left the British troops exhausted and still facing the Americans across the creek as darkness descended. Both sides set out pickets and prepared for the next day's big battle. Washington called a council of war, and while he probably knew exactly what he wanted to do, the officers present felt they made a unanimous decision. They would march overnight to Princeton while avoiding detection by Cornwallis and attack the small Princeton garrison before moving on to Brunswick. They could then move on to Morristown, and the British would hopefully abandon most of New Jersey.

This was not a plan to extricate himself from a self-imposed trap, but rather was part of Washington's overall plan to force the British from New Jersey by taking advantage of the weaknesses in their chain of cantonments. Washington wanted to avoid a large pitched battle with the full British army, one such as Cornwallis eagerly anticipated the next morning. A British officer later wrote that "Mr. Washington, whom we have already seen capable of great and daring enterprise [ at Trenton] ... and surprising the intermediate posts of communication by unexpected and rapid movements, ... conceived the idea of stealing a march on the royal army" which was at that time "harassed and jaded by the long march, and the bad roads." He believed Washington's men were relatively fresh, "his intelligence good, and his knowledge of the country, through all the cuts and bye-roads, perfect:" Therefore, "[i]t must be allowed, the deception was admirable, and it was conducted in a masterly manner; it deserves a place amongst distinguished military achievements, and was worthy of a better cause."

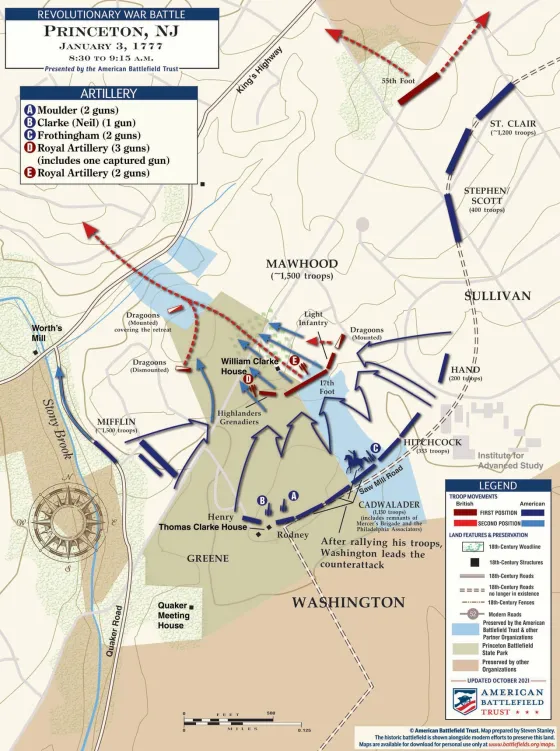

The secrecy of the plan was so complete that when the soldiers set out quietly marching to Princeton, they had no idea where they were going. Some men did not get the word and were left behind. Just after daylight, the overnight marchers surprised British forces marching out of Princeton toward Trenton to assist Cornwallis in his renewed attack on Washington. After the initial encounter resulted in confusion and retreat by troops of Mercer's and Cadwalader's brigades, Washington, seeing the problem, ordered Hand's and Hitchcock's brigades to go to their assistance. Washington personally led them across Maxwell's Field to steady the troops. Sergeant Nathaniel Root was in retreat when he saw Washington at the head of the troops coming to help the re-treating troops and heard him yell, "Parade with us, my brave fellows, there is but a handful of the enemy, and we will have them directly." Root, along with others, "immediately joined the main body, and marched over the ground again." In a short time, the British were completely defeated, and those not captured fled the area.

Philadelphia Associator James Read later exclaimed to his wife, "O my Susan! It was a glorious day and I would not have been absent from it for all the money I ever expect to be worth." He wrote of Washington, "[I]t is not in the power of language to convey any just idea of him. His greatness is far beyond my description. I shall never forget ... when I saw him brave all the dangers of the field, and his important life hanging as it were by a single hair with a thousand deaths flying around him .... He is surely America's better Genius and Heaven's peculiar care." Washington's leading troops across Maxwell's Field was an important highlight in the success of the Revolution and the establishment of his leadership.

While the troops were far too fatigued to advance on Brunswick, Washington did get them to Morristown over the next few days, where the Continental Army was able to rebuild during the winter. American troops were able to keep the British at Brunswick extremely uncomfortable and subject to a "Forage War" until spring, when the British troops did leave New Jersey. Although more military encounters occurred in New Jersey during the American Revolution than in any other state, the British never again occupied the state as they did in December 1776.

The victories of the Ten Crucial Days caused "an amazing alteration in the faces of men." When they told the story of the campaign, "the tidings flew upon the wings of the wind - and at once revived the hopes of the fearful, which had almost fled! How sudden the transition from darkness to light; from grief to joy!" As for the British, Lord Germain commented to Parliament in 1779 that "all our hopes were blasted by that unhappy affair at Trenton." Their hopes were not just blasted by the engagement at Trenton, but also the decisive and audacious victories over the entire Ten Crucial Days.