The Battle of Cold Harbor was one of the Civil War's most dramatic and decisive engagements. Please consider these 10 facts to expand your knowledge and appreciation of the American Battlefield Trust's ongoing preservation efforts on the historic battlefield.

Fact #1: The Battle of Cold Harbor, Virginia was a sprawling, two week engagement that left more than 18,000 soldiers killed, wounded, or captured.

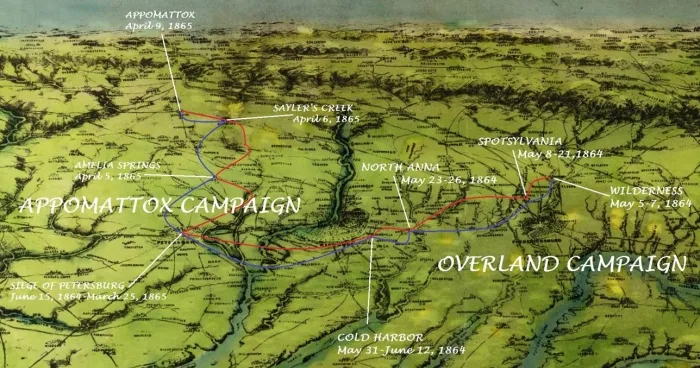

In the summer of 1864, the Union Army of the Potomac was fighting its way south towards Richmond, Virginia. In a series of battles collectively known as the Overland Campaign, the Union army had suffered more than 50,000 casualties but had also forced Robert E. Lee’s hard-bitten Confederate veterans to abandon much of northern Virginia. The small crossroads of Cold Harbor, just ten miles north of Richmond, became the focal point of the action in late May. From May 31-June 3, Ulysses S. Grant ordered repeated attacks against entrenched Confederate positions, culminating in an enormously bloody repulse on June 3. Both armies held their ground and kept up a withering fire between the lines until June 12, at which point Grant withdrew but continued to move east and south. The Army of the Potomac crossed the James River and, by June 16, was in position to directly threaten the manufacturing and rail center of Petersburg—the back door to Richmond.

Fact #2: The Confederate line was nearly broken on June 1.

Union cavalrymen captured the Old Cold Harbor crossroads on May 31. Early on June 1, Confederate infantry attacked the Union troopers but were driven back with heavy losses—the repeating carbine had drastically improved the combat power of the cavalry. Union infantry reinforcements arrived throughout the day. In the evening, the Federals managed to pierce a weak seam between two Confederate brigades before being repulsed by a desperate counterattack. The day’s fighting cost the two armies roughly 4,000 casualties. Ulysses S. Grant planned another attack for June 2 but postponed it until June 3 in order to give newly arrived soldiers time to rest. Robert E. Lee used the time to greatly strengthen his position. By the end of the day, the Confederates were protected by “a maze and labyrinth of works within works,” according to a Northern journalist.

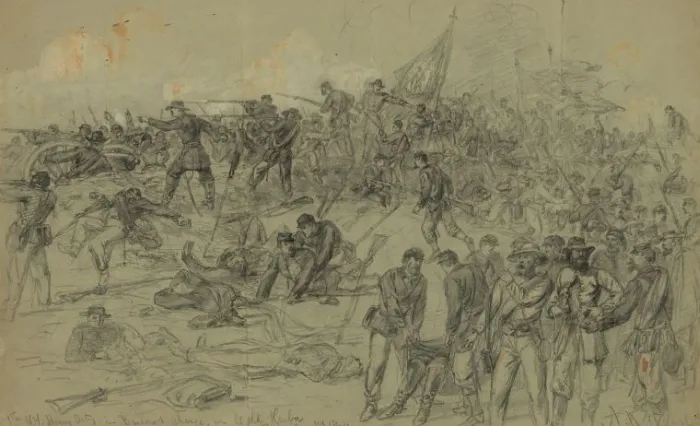

Fact #3: Approximately 6,000 Union soldiers were killed, wounded, or captured during the June 3 assault.

When the orders for a full-scale assault began to filter through the army on June 2, many Union officers were gravely concerned. Neither Grant nor George Meade, his second-in-command, had personally observed the heavily fortified Confederate line. Furthermore, the orders did not specify a particular target of the attack and they did not appear to coordinate the efforts of the different parts of the army. Major General William F. “Baldy” Smith, commanding the 18th Corps, was “aghast at the reception of such an order, which proved conclusively the utter absence of any military plan.” Colonel Horace Porter remembered infantrymen attaching name tags to their uniforms for later identification if killed on the field—a precursor to the official G.I. dog tags introduced in World War I. When the attack went forward at 4:30 a.m. on June 3, the soldiers “went down like rows of blocks” under crushing Confederate fire. The scene was chaotic and terrifying—successive lines mixing into pushing, shoving crowds as tens of thousands of men tried to stay alive in the open fields in front of the seething Southern breastworks. Grant suspended the offensive at noon, and would later claim to have “always regretted that the…assault was ever made.” The Confederates suffered about 1,500 casualties, losing one man to every four fallen Federals.

Fact #4: Wounded Federal soldiers were left on the battlefield for four days after the June 3 assault.

The massive assault on June 3 ended with Union soldiers using cups, bayonets, and their hands and feet to dig out rudimentary protection under the mouths of the Confederate guns. These were quickly developed into more elaborate entrenchments, although in some places the opposing lines were less than 75 yards apart. Sharpshooting was particularly fierce for days. Ulysses S. Grant, perhaps unwilling to admit defeat, delayed the process of requesting a formal truce to gather the several hundred wounded that were immobile between the lines. It was not until June 7 that the terms were arranged and Union soldiers ventured into no-man’s-land to recover their comrades. Most of them had already died. One Federal remembered that “I saw no live man lying on this ground. The wounded must have suffered horribly before death relieved them, lying there exposed to the blazing southern sun o' days, and being eaten alive by beetles o' nights.”

Fact #5: The Battle of Cold Harbor was Robert E. Lee’s last large-scale field victory.

Derisively referred to as the “King of Spades” early in the war, a dig against his perceived proclivity for static defense and entrenchment, Robert E. Lee quickly proved his detractors wrong with a series of audacious maneuvers and correspondingly stunning victories. The successes of the Seven Days, Second Manassas, and Chancellorsville were all sourced in Lee’s talent for moving his army with a speed and precision that stymied his Union opponents. At Cold Harbor, the Union Army suffered heavily after Lee guided his men into impregnable positions threatening the Federal line of advance. By late June, however, less than two weeks after the end of the battle, Lee had been forced to submit to a siege around Richmond and Petersburg. He held the cities for another nine months and not only bitterly contested each Union offensive, but also won some battles at places like Reams Station with portions of his army. Most of his army was frozen in place, however, and was absolutely required to man the trenches, or else Petersburg and Richmond would be lost to the Federals. When the line was finally broken, the Army of Northern Virginia’s final field campaign was a week-long string of disasters.

Fact #6: Despite the Confederate tactical success, the Battle of Cold Harbor was a strategic turning point in the Civil War, after which there was little chance for overall Confederate victory.

Edward Porter Alexander, the Southern artillery officer who orchestrated the guns before Pickett’s Charge and served as one of Lee and Longstreet’s most consulted aides, called the Battle of Cold Harbor “our last, and perhaps our highest tide.” After the suffering of the Overland Campaign, in which more than 50,000 Union soldiers fell in less than two months, Alexander believed that halting Grant’s army north of the James River, “no nearer Richmond…than his ships might have landed him at the beginning without the loss of a man,” would have turned the Northern public strongly against further prosecution of the war. Robert E. Lee himself believed that “we must destroy this army of Grant’s before he gets to the James River. If he gets there, then it will be a siege, and then it will be a mere question of time.” Despite the staggering losses at Cold Harbor, Grant managed to withdraw in good order and then deceive the Confederates for critical days as his army crossed the James River and marched towards Petersburg, where Lee’s grim prediction was confirmed.

Fact #7: Cold Harbor was neither cold nor accessible by boat—the name is a confluence of Old High German and local branding.

The area of Cold Harbor, Virginia, gets its name from the two Cold Harbor taverns (Old and New), which both stood near the contested crossroads in 1864. In 5th century Germany, the words “heer” and “bergen” meant “army” and “shelter,” respectively. This concept eventually arrived in Middle English as “herber,” meaning a way station or an inn. Today, “harbor” more commonly refers to a seaport or dock, but the term’s more archaic root as a “shelter” can still be found in “harboring a fugitive” or “harboring a grudge,” among others. The reasoning behind the use of the word “Cold” is less clear, as Cold Harbor is hot and humid landscape for much of the year. Many believe that the adjective was used to describe the Old Cold Harbor Tavern’s amenities, or lack thereof, for it is said that owner Isaac Burnett only served cold meals, or perhaps no meals at all. Union officers became confused by the Old/New distinction during the battle, and many mistakenly referred to the area as Cool Arbor.

Fact #8: The Battle of Cold Harbor was fought on some of the same ground as the 1862 Battle of Gaines’ Mill.

In late June 1862, the Union and Confederate armies were locked in combat just outside of Richmond. Robert E. Lee, only recently placed in command of the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia, had launched a bold offensive in an effort to force George McClellan and the Army of the Potomac away from the capital. On June 27, a large battle, commonly known as the Battle of Gaines’ Mill, broke out near the Old Cold Harbor crossroads as a Union rear-guard force withstood repeated Confederate assaults. The Confederates broke the Union line at nightfall and sent a chill through McClellan, who ordered his army to retreat all the way to a new supply base on the James River. In early June 1864, not quite two years later, the fortunes of war brought the armies back to the old battlefield, but with their roles reversed.

Fact #9: Cold Harbor was extensively photographed during and after the battle.

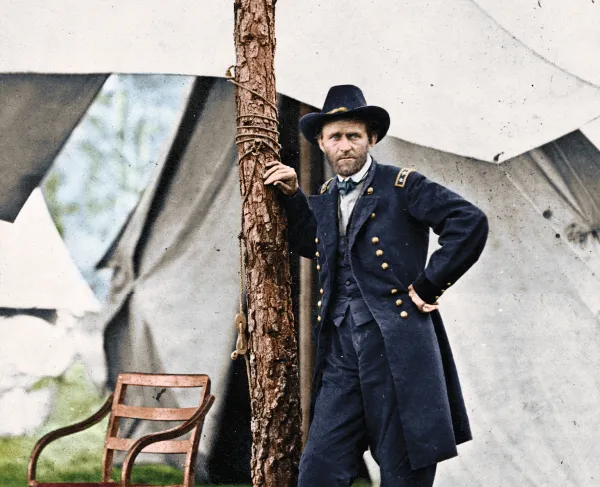

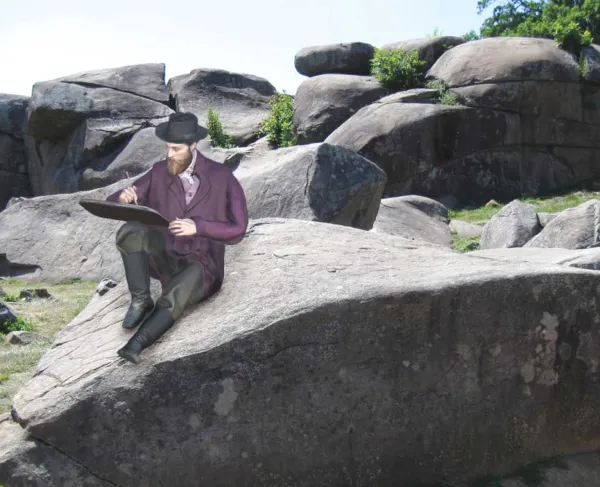

In order to document a battlefield, Civil War photographers needed a variety of circumstances to correctly align. They needed time to travel to the scene and strong indications that the photographic opportunities warranted the effort of sending a mobile studio. Most importantly, the field had to still be in Union hands. Since only part of the battlefield was under Union control, photographers recorded photos of Union camps, including most of the officers of the Union high command. These photographs, taken during a period of extreme tension, are unusually revelatory of their subjects. A photographer returned in 1865 to shoot parts of the battlefield, including Confederate fortifications and horrific scenes showing decomposed soldiers undergoing burial operations.

Fact #10: The American Battlefield Trust has saved important parcels of land at Cold Harbor.

In December 2013, the American Battlefield Trust helped save six crucial acres at the Cold Harbor battlefield that is contiguous with National Park Service property. This land, roughly half a mile northwest of the crossroads itself, was the scene of sharp fighting on June 1 as soldiers of the Union Eighteenth Corps pushed through the advanced lines of Joseph B. Kershaw’s Southern division. On June 3, more Federal soldiers used the land to form up for the day’s fateful charge while under a destructive artillery fire. Nearly half of the men who formed on those six acres were killed or wounded within twenty minutes of the attack orders being given.

Learn More: The Overland Campaign Animated Map

We have a chance to save these critical pieces of history at Gaines' Mill, Cold Harbor, and Appomattox Court House for just a fraction of their full...

Related Battles

12,737

4,595