In a way, the American Revolution began with acts of espionage. Even a month before “the shot heard ‘round the world” Thomas Gage, the royal governor of Massachusetts, sent two subordinates to travel to Concord in March 1775 to gather information about patriots’ intentions and stockpiles of supplies and weapons. When British troops finally headed to Concord in April, their march was hardly the surprise that was intended—did someone close to the royal governor alert the patriots of their approach?

During the American Revolution, both the British and patriot armies employed spies to gather information about the enemy. Both armies relied on spies to gather information on troop strength and morale, access to and availability of munitions and supplies and intended plans to march or attack. British commanders found intelligence gathered by loyalist sympathizers useful, which often included details about geography and terrain unfamiliar to the British army. Some spies served for long periods or even the duration of the war, while others performed only singular acts of espionage when duty called, or when opportunities presented themselves. Both armies also mounted misinformation campaigns, purposefully leaking false intelligence for the enemy to find.

General George Washington was keenly aware of the importance of espionage during the war. In 1777 he wrote to Colonel Elias Dayton, “The necessity of procuring good Intelligence is apparent & need not be further urged -- All that remains for me to add is, that you keep the whole matter as secret as possible.” British General Charles Cornwallis, too, understood the importance of clandestine intelligence gathering and is reported to have exclaimed, “Ah, you rogue!” upon the realization that his own trusted spy was, in fact, a double-agent for Washington. It is clear that Washington’s tactics were no match for British intelligence agents, one of whom later said, “Washington did not really outfight the British. He simply out-spied us.”

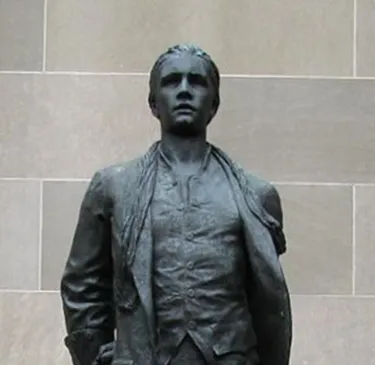

At the start of the war, Washington quickly recognized both the importance of counterintelligence and stopping intelligence gathering by the enemy, as well as placing his own spies behind enemy lines. In June 1776, Washington placed John Jay at the head of New York’s newly created Committee on Detecting and Defeating Conspiracies. Jay’s directive from Washington was to “close the regular channels of intelligence from the city.” One of the first agents acting on behalf of the patriots was Nathan Hale, who volunteered to spy on the British on Long Island in September 1776. Quickly captured, the British hanged Hale as a spy. A witness reported that Hale uttered a patriotic sympathy in his last breath: “I only regret that I have but one life to lose for my country.”

As Washington was quick to employ spies for his own benefit, he was also menaced by spies and fake intelligence coming from British agents and loyalist sympathizers. For years during the war, Washington was particularly vexed by New Jersey loyalist James Moody. Though James was routinely able to intercept official correspondence and even some of Washington’s own letters, officials could never try him as a spy. When Moody was finally captured in 1780 Washington wrote, “It is a pity but that Villian Moody could be apprehended lurking in the Country, in a manner that would bring him under the description of a Spy. When he was taken before, he was in Arms—in his proper uniform…it was, therefore, a matter of great doubt whether he could be considered otherwise than a prisoner of War.” Moody escaped and later wrote his memoir as a loyalist spy and recruiter during the war.

Many spy rings were active during the American Revolution, but perhaps the most famous is the Culper Spy Ring, comprised of a group of civilian and military officials working together to gather intelligence for Washington while the British army occupied New York. Under the direction of Benjamin Tallmadge, agents Abraham Woodhull, Caleb Brewster, Anna Strong, Austin Roe, and others spied on the British beginning in 1778 and for the duration of the war. The agents choose pseudonyms—Tallmadge was known as “John Bolton,” while Woodhull became known as Samuel Culper, the namesake of the group. Tallmadge also devised a numerical substitution system, with numbers standing in for words, locations, and important names (for example, Washington’s numerical code was 711). The spy ring employed systematic tactics of dead drops, codes were hidden in plain sight (a petticoat hanging from Anna Strong’s clothesline could indicate the location of a meeting or that a message was available at a dead drop), and even messages written in invisible ink with ciphers and coded letters. Washington himself was active in directing the agents’ secret communications. From his headquarters at West Point in September 1779, Washington wrote to Tallmadge instructing agents to write messages with invisible ink on pocketbooks, almanacs, or pamphlets, which British agents were less likely to search than common letters. The Culper Ring was extremely successful and is responsible for uncovering a British plan to bombard the French fleet off the coast of Rhode Island.

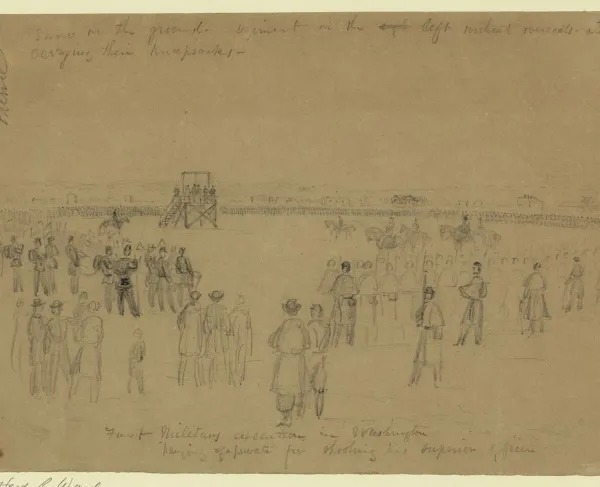

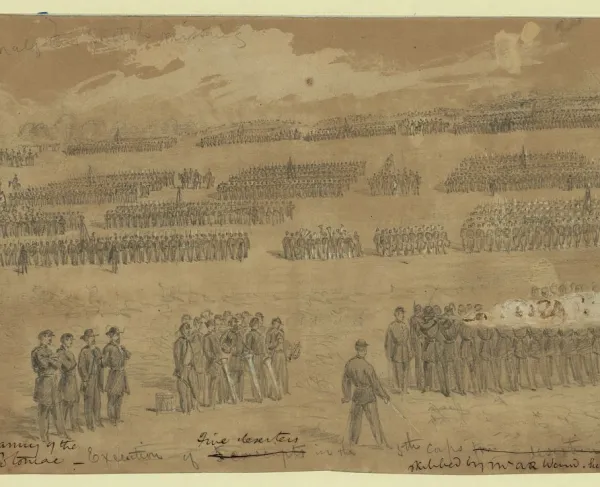

Historians also credit the Culper Ring with uncovering Benedict Arnold’s treasonous turn to the British and, indirectly, exposing Major John André, Arnold’s British accomplice and head of the British secret service in America. After rendezvousing with Arnold regarding plans for the British to capture West Point André, dressed in civilian attire, was stopped and questioned by three patriot militiamen. André aroused the men’s suspicions and upon searching his person, the militiamen found a map of West Point and other incriminating papers hidden in André’s boot. George Washington ordered him to be hanged, possibly in retaliation for the treatment of Nathan Hale at the hands of the British. In an emotional and very public affair, André was hanged on October 2, 1780, with thousands of onlookers in attendance.

While André attempted to hide intelligence in his boots, British General William Howe sent a secret message to General John Burgoyne rolled up and hidden inside a large quill. Patience Lovell Wright, an America-born artist living in London, sent secret messages across the Atlantic hidden in the wax busts she sculpted. Wright corresponded with Benjamin Franklin and Thomas Jefferson, and kept them informed of the gossip and plans she overheard among the inner circles of king and Parliament. Wright sent messages through her sister Rachel as well, who later wrote of her sister’s exploits, “how did she make her Cuntry[sic] her whole attention, her Letters gave us ye first alarm…she sent Letters in buttons & pictures heads to me, ye first in Congress attended Constantly to me for them in that perilous hour.”

Like Patience, many spies in the Revolution were civilians. As armies occupied major cities and took over the homes and farms of colonists, men and women overheard or otherwise chanced upon information and risked their lives to get messages to colonial leaders and generals. In 1777, British troops occupied the Philadelphia home of Quaker Lydia Darragh, who hid in a closet to eavesdrop on a secret meeting pertaining to a surprise attack on Washington’s troops. Darragh obtained a pass to travel through the city and met with patriots at the Rising Sun Tavern, whom she informed of the plan. Though she was later questioned by British authorities when it became evident the attack was not a surprise, she was never suspected. There are many stories similar to Lydia’s, in which women were able to pass messages across the enemy lines. When Deborah Champion hid papers in her saddlebag to deliver them to Washington for her father, the fact that she was a woman caused a British soldier to dismiss her as suspicious. According to one source, the soldier glanced at Deborah and said, “you are only an old woman anyway,” and let her on her way to complete her mission. However, Champion’s tale of delivering a letter to Washington may not be entirely accurate. While some daring acts of espionage have been documented and corroborated by primary sources, far more survive in the form of local and family legend or lore.

A more documented instance of civilian espionage is the New York tailor Hercules Mulligan. By 1775 Mulligan was a well-known tailor who catered to patriots and loyalists alike, and even served British soldiers. When British soldiers arrived at his tailor shop, Mulligan took an active interest in their needs, and learned much about the activities or planned activities of the troops. For example, if a customer needed coat repairs completed in a matter of days, Mulligan could inform Washington that the British were planning to move. While Mulligan communicated directly with the British inside his shop, his slave Cato took the intelligence to Washington. Under the guise of delivering clothing or packages, Cato passed under the unsuspecting eyes of enemy soldiers in his way. Cato was just one of many African Americans, enslaved and free, who spied during the war.

Famously, an enslaved man named James Armistead infiltrated Cornwallis’ camp at Yorktown and communicated with the Marquis de Lafayette. Lafayette, in turn, wrote to Washington of his well-placed “friend,” who acted as “servant to Cornwallis,” and looked through his papers, was present at dinners and important meetings, and saw first-hand the health and supply of British troops on the eve of 1781’s Siege of Yorktown. Some historians believe that Cornwallis asked James to spy for the British, making James a double agent. A 19th-century anecdote describes the scene of Cornwallis recognizing James at Lafayette’s and Washington’s side after the surrender at Yorktown. Realizing he had been had, Cornwallis is reported to have exclaimed, “Ah you rogue, then you have been playing me a trick all this time!” James likely was not the only spy who helped ensure the patriot victory at Yorktown in 1781. Even before the Continental Army turned south, Washington used his network to leak false information about his plans to meet Cornwallis in Virginia. The Marquis de Lafayette also embarked on a false information campaign, and sent a soldier into Cornwallis’s camp posed as a deserter to feed him fake news about the Continental Army.

Just as spies may have influenced the events of Lexington and Concord in April 1775, spies helped ensure the patriot victory at Yorktown in 1781. Whether informants were civilians or military officials or soldiers, long acting in the service of their country or seizing unique opportunities, spies undoubtedly played a crucial role in the American Revolution.

Test Your Knowledge

Further Reading:

- Spies, Patriots, and Traitors: American Intelligence in the Revolutionary War By: Kenneth A. Daigler

- The Fox and the Hound: The Birth of American Spying By: Donald Markle

- Spying in America: Espionage from the Revolutionary War to the Dawn of the Cold War By: Michael J. Sulick