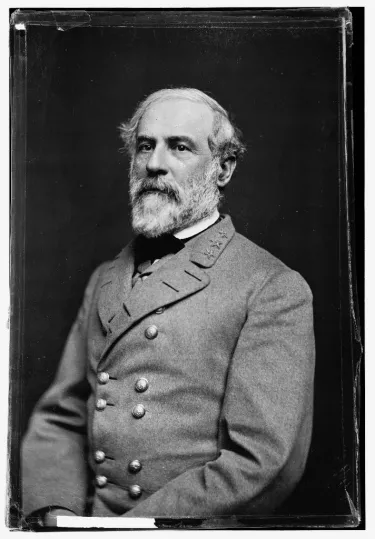

Proving his skeptics wrong, Robert E. Lee took command of the Confederate Army at Richmond and after the Seven Days Battles pushed back Union forces and ensured his reputation as a brilliant commander.

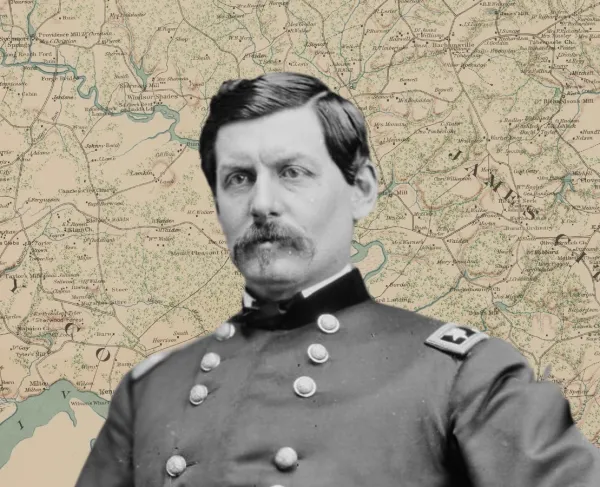

On June 1, 1862, Robert E. Lee replaced a wounded Joseph E. Johnston as the commander of the Confederate army defending Richmond. This change of leadership occurred as George B. McClellan and his Army of the Potomac, which numbered more than 100,000 men, approached the climax of their grand offensive against the Southern capital. Although Lee later achieved a towering reputation, news of his appointment provoked widespread concern across the Confederacy. A North Carolina woman gave voice to a common evaluation of Lee:

"I do not much like him, he 'falls back' too much ... His nick name last summer was 'old-stick-in-the-mud' ... There is mud enough now in and about our lines, but pray God he may not fulfill the whole of his name."

The next five weeks proved Lee's doubters wrong. No general exhibited more daring than the new Southern commander, who believed the Confederacy could counter Northern numbers only by seizing and holding the initiative. He spent June preparing for a supreme effort against McClellan. When "Stonewall" Jackson's command from the Shenandoah Valley and other reinforcements arrived, Lee's army, at nearly 90,000 strong, would be the largest Confederate force even placed in the field. By the last week of June, the Army of the Potomac lay astride the Chickahominy River, two-thirds of its strength south of the river and one-third north of it. Lee hoped to crush the portion north of the river then turn against the rest. Confederates repulsed a strong Union reconnaissance against their left on June 25, opening what became known as the Seven Days Battles and setting the stage for Lee's offensive.

Heavy fighting began on June 26 at the Battle of Mechanicsville and continued for the next five days. Lee consistently acted as the aggressor but never managed to land a decisive blow. At Mechanicsville, he expected Jackson to strike Union General Fitz John Porter's right flank. The hero of the Valley failed to appear in time, however, and A. P. Hill's Confederate division launched a futile frontal assault about mid-afternoon. Porter retreated to a strong position at Gaines's Mill, where Lee renewed his offensive on the 27th. Once again Jackson stumbled, as more than 50,000 Confederates mounted savage attacks along a wide front. Late in the day, Porter's lines gave way, and he withdrew across the Chickahominy to join the rest of McClellan's army. Jackson's poor performance, usually attributed to exhaustion verging on numbness, joined poor staff work and other factors in allowing Porter's exposed portion of McClellan's army to escape.

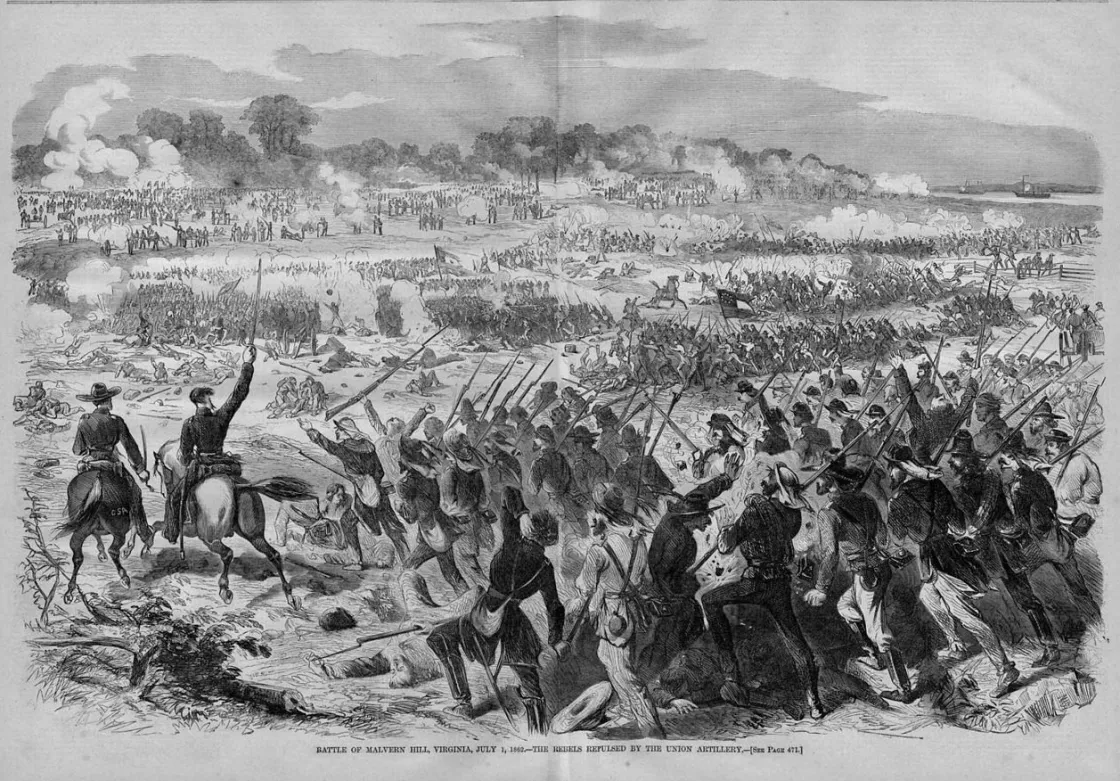

In the wake of Gaines's Mill, McClellan changed his base from the Pamunkey River to the James River, where Northern naval power could support the Army of the Potomac. Lee followed the retreating McClellan, who insisted the Rebels badly outnumbered his army, seeking to inflict a crippling blow as the Federals retreated southward across the Peninsula. After heavy skirmishing on June 28, the Confederates mounted ineffectual attacks on the 29th at Savage's Station and far heavier ones at Glendale (also known as Frayser's Farm) on the 30th. Stonewall Jackson played virtually no role in these actions, as time and again the Confederates failed to act in concert. By July 1, McClellan stood at Malvern Hill, a splendid defensive position overlooking the James. Lee resorted to unimaginative frontal assaults that afternoon. Whether driven by vexation at lost opportunities or his natural combativeness, he had made one of his poorest tactical decisions. Southern division commander Daniel Harvey Hill famously said of the action on July 1, "It was not war, it was murder." As evening fell, more than 5,000 Confederate casualties littered the slopes of Malvern Hill. Some of McClellan's officers urged a counterattack against the obviously battered enemy; however, "Little Mac" retreated down the James to Harrison's Landing, where he awaited Lee's next move and issued endless requests for more men and supplies.

Casualties for the Seven Days were enormous. Lee's losses exceeded 20,000 killed, wounded, and missing, while McClellan's surpassed 16,000. Gaines's Mill, where combined losses exceeded 15,000, marked the point of greatest slaughter. Thousands of dead and maimed soldiers brought the reality of war to Richmond's residents. One woman wrote, "death held a carnival in our city. The weather was excessively hot. It was midsummer, gangrene and erysipelas attacked the wounded, and those who might have been cured of their wounds were cut down by these diseases."

The campaign's importance extended far beyond setting a new standard of carnage in Virginia. Lee had seized the initiative, dramatically altering the strategic picture by dictating the action to a compliant McClellan. Lee's first effort in field command lacked tactical polish but nevertheless generated immense dividends. The Seven Days Battles saved Richmond and inspirited a Confederate people buffeted by dismal military news from other theaters. The victory also caused Lee's reputation to shoot upward, beginning the process by which he and his army would emerge, by the late spring of 1863 at the latest, as the principal national rallying point for the Confederate people. One of the Richmond newspapers captured this element of the campaign's aftermath when it commented that "the brilliancy of Lee's genius" manifested at the Seven Days had "established his reputation forever, and ... entitled himself to the lasting gratitude of his country."

On the Union side, the campaign dampened expectations of victory that had mounted steadily as United States armies in Tennessee and along the Mississippi River won a string of successes. McClellan's failure also exacerbated political divisions in the United States, clearing the way for Republicans to implement policies that would strike at slavery and other Rebel property. The end of the rebellion had seemed to be in sight when McClellan prepared to march up the Peninsula; after Malvern Hill, only the most obtuse observers failed to see that the war would continue in a more comprehensive manner. "We have been and are in a depressed, dismal, ... state of anxiety and irritability" wrote a perceptive New Yorker after McClellan's retreat. "The cause of the country does not seem to be thriving just now."

The campaign also underscored the degree to which events in the Virginia theater dominated perceptions about the war's progress. Despite enormous Northern achievement in the western campaigns, most people North and South, as well as observers in Britain and France, interpreted the Seven Days as evidence that the Confederacy was winning the war. Lincoln wrote about this phenomenon in early August, complaining that "it seems unreasonable that a series of successes, extending through half-a-year, and clearing more than a hundred thousand square miles of country, should help us so little, while a single half-defeat should hurt us so much." Lincoln did not exaggerate the impact of McClellan's failure. Taken overall, the ramifications were such that the Richmond campaign must be reckoned one of the turning points of the war.

We have a chance to save these critical pieces of history at Gaines' Mill, Cold Harbor, and Appomattox Court House for just a fraction of their full...

Related Battles

6,800

8,700

3,797

3,673

2,100

5,600