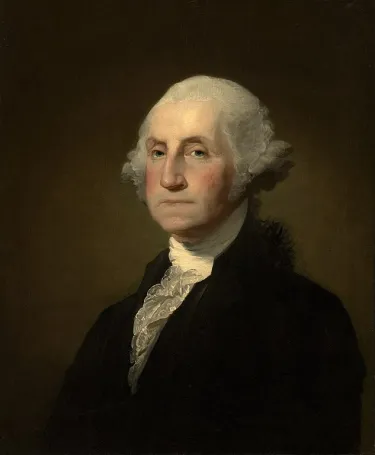

President George Washington

When George Washington stepped out onto the pavilion at Federal Hall in New York City on April 30, 1789, he was making history yet again. Newly fifty-seven years old, the American had been unanimously elected as the first president of the United States following the intense ratification debates that enshrined the Federal Constitution and federal government as the modes for how the young country would function. Washington had been masterful in his position as serving as president over the Philadelphia Convention. While rarely speaking during deliberations, he, in fact, would not stop speaking in private about why the Constitution had to be ratified. Along with other Federalists, Washington spent considerable time in the evening hours hammering out differences among colleagues and persuading wary delegates to sign off on the new government. Many of them did so on the promise that it was Washington, and the reputation that he carried, who would oversee the new government.

As had been the case leading up to the Constitutional Convention, friends and colleagues pressured Washington to accept the presidency because no one else could. Twice now retired, the former American general did not want to step back into the public square. With his reputation intact as the hero of the Revolution, and now eyeing retirement as a full-time planter at Mount Vernon, the last thing Washington wanted was to risk damaging the respect and reputation that he painstakingly earned through years of personal sacrifice. Nevertheless, Washington was as committed to seeing the new government succeed as anyone. He had staked much of his energies into ratification. Perhaps one of the strongest letters of insisting he was the only candidate for the job, friend and fellow Federalist Gouverneur Morris wrote to Washington on October 30, 1787, saying among other things, “I will add my Conviction that of all Men you are best fitted to fill that Office. Your steady Temper is indispensably necessary to give a form and manly Tone to the new Government….They will listen to your Voice, and submit to your Control; you therefore must I say must mount the Seat.”

Others voiced similar calls to Washington that it had to be him to lead the country as he had done before. These were uncertain times. The Constitution had not been tried; the new separation of powers was still a concept untested, and Antifederalist opponents readily waited for the whole thing to fall apart to cede control back to the way things were under the Articles of Confederation. No, if there was one individual who would project faith in the new experiment of self-government, it would have to be the one individual most Americans trusted. Washington, too, knew it could only be him. He reluctantly accepted the presidency under the hope that it would only be a temporary position; perhaps he could be the figurehead to set the course and pass it off to someone who actually wanted the job within a year. Events, however, would consume the first president and keep him at the head of the federal government far longer than he ever wanted.

Newspapers fawned over the president’s ascendence to lead the new government. Poems and stories were printed by the dozens in the spring of 1789 to celebrate Washington once again assuming the leadership of the country. Even rivals, few that there were, reluctantly agreed that if anyone deserved the chance to make the government work, it was him. Ironically, one of the first crises to hit the new administration involved Washington himself. The president developed an abnormal growth on his upper thigh which had to be surgically removed in June 1789. He spent much of the summer laid up in bed, unable to walk or sit without excruciating pain. The second ailment to strike the president occurred the following spring. This time proved to be far more serious as he contracted a virulent strain of influenza which weakened him so much that the New York press began circulating rumors that Washington was close to death. As Abigail Adams wrote on May 30, 1790, “It appears to me that the union of the states, and consequently the permanency of the Government depend under Providence upon his Life. At this early day when neither our Finances are arranged nor our Government sufficiently cemented to promise duration, His death would I fear have had most disastrous consequences.” Her convictions echoed those of nearly every American, friend or foe: if Washington were to die, the legitimacy of the new government would potentially die with him.

Health scares aside, the first year of his presidency was relatively quiet, which undoubtedly aided in his recovery. The first real test for the new government came from the First Congress in May 1789 when Virginia delegate Josiah Parker proposed a bill that would put a tax on importing slaves into the country. Though the Constitution did not specifically mention slavery, the document and the federal government had enshrined its existence and practice into law so long as it remained isolated to the South. The new bill threatened to unravel the careful agreements that had been made during the Convention to ease sectional tensions. After many of the southern delegates objected, the bill eventually was pulled. But the issue would not disappear. Pennsylvania, long the bastion of Quaker influence, now saw numerous abolitionist groups rise just as Philadelphia was set to become the temporary capital. Suspicions among Southern politicians would reanimate sectional tensions that never entirely ceased.

Slavery would remain a contentious aspect of Washington’s tenure as president. As a slaveowner whose life revolved around its servitude to the needs of his family, he could not live without it. In 1791, Washington toured the Southern states in what became a ‘grand tour.’ During this escape from Philadelphia, the president faced a minor crisis along the Georgia-Spanish Florida border. Runaway slaves were settling in Florida and threatening the stability of the Georgian government. Washington ordered the border closed and that all runaway individuals be returned to their masters. At another point in the trip, Washington confessed to South Carolina’s Charles Pinckney his displeasure with a failure to prohibit the slave trade, saying, “I was in hopes that motives of policy, as well as other good reasons supported by the direful effects of Slavery which at this moment are presented, would have operated to produce a total prohibition….” Of course, this contradiction would be played out by Washington himself.

As the federal capital temporarily moved to Philadelphia in 1791, the Washington family faced a dilemma. Under the Pennsylvania Constitution, any person held in bondage who remained within the state for more than six months would be considered free. Having no interest in losing their personal servants, the Washingtons concocted a scheme to rotate their slaves out of Philadelphia every six months. Among the members of the Washington presidential household to escape during his time in Philadelphia were Ona Judge, Martha Washington’s personal servant, and Hercules, the family cook. Washington signed the Fugitive Slave Law of 1793 that allowed slave-catchers to enter Northern states and reclaim their property. Yet in 1794, Washington wrote privately his personal disdain for slavery and wishing for a way to abolish the institution. The contradiction continued as Washington sought means of bringing Judge back, at one point sending a cousin to kidnap her in New Hampshire. She escaped with the help of locals and remained free for the rest of her life.

The other major issue pressing the new administration in 1790 was Treasury Secretary Alexander Hamilton’s financial plan. The Assumption Plan or later the Funding Act of 1790 gave Hamilton his great scheme of doing away with the leftover debt from the American Revolution. The remaining debt from the war was discharged onto the federal government, creating national credit. The government would then issue bonds to the former debt holders, ensuring their value. Hamilton’s other great scheme was the creation of a national bank, further insuring the solvency of the credit of the United States. Opposition to the plans was fierce, led chiefly by Secretary of State Thomas Jefferson. Like others in the Antifederalist crowd, Jefferson was strongly skeptical of a powerful centralized government controlling finances. He further worried if the eventual goal was to establish a monarchial system that favored the Northern merchant class based in New York. Jefferson, himself a lifelong debtor to creditors, never trusted Hamilton, though the two political enemies did reach a compromise on another looming issue for the administration to settle.

New York City had lost the bid to become the permanent seat of government over fears from Southern politicians that Northern interests would outweigh the interests of other parts of the continent if the capital remained in the North. Philadelphia strongly bid for the capital seat, as did counties in western Pennsylvania. Washington, Jefferson, James Madison, and other Southerners wanted the capital to be in the South. Virginia remained the most powerful state in the Union at the time, and Washington, using his considerable leverage, argued for a site of his choosing along the Potomac River. Seeing the advantage of having the capital in Virginia, Jefferson and Madison approached Hamilton with a solution. If Hamilton were to convince his Federalist allies in the North to vote for the capital in the South, Jefferson and Madison would throw their support behind Hamilton’s Assumption bill. The Residence Act of 1790 stipulated that the new capital had to be ready to receive the federal government in ten years, or it would forfeit its bid. The project would become the main focus of Washington’s tenure as president. It became such a boondoggle and strife with uncertainty within just two years that Washington feared if he left office after one term, the future city would never get built.

In 1791, Washington faced two new crises, one on the home front and one overseas. The United States had gained massive amounts of land west of the Appalachian Mountains with the Treaty of Paris in 1783. The Northwest Ordinance of 1787 had settled much of this territory in terms of ownership among the United States. The territory was owned by states like Massachusetts and Connecticut, who then began selling off large parcels of land to investors, speculators, and settlers. The problem was much of this land was still lived upon by various Native American tribes collectively known as the Western Confederacy. And to complicate matters more, both Great Britain and Spain, who maintained territories on the borders, were instigating the tribal confederacies to harass Americans traveling west. For several years, skirmishes broke out between Indian nations and encroaching settlers. News reports of Indian raids brought long-held colonial fears and prejudices roaring back. Envoys did little to settle the warring parties among the Western Confederacy in modern-day Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, and Michigan. Washington dispatched Maj. Gen. Arthur St. Clair with a detachment of 1,000 US Army troops to Ohio to put down the raiding parties. On November 4, 1791, St. Clair’s entire force was nearly wiped out by an ambush. When word reached Philadelphia, Washington was seated entertaining dinner guests. He abruptly excused himself to a side room where he stood leaning over the mantel. The usually contained Washington was furious. Considering his own long history with Native Americans, he reportedly fumed, “He did not listen to my advice. What was he thinking?” Peace delegations from several tribes arrived in Philadelphia, and Washington greeted them cordially. Philadelphia had long been a diverse city, and the history of fairly good relations between Indians in the Delaware Valley resulted in their presence being a common sight in the city. Meanwhile, St. Clair was replaced with Maj. Gen. “Mad” Anthony Wayne whose victory three years later, known as The Battle of Fallen Timbers, would help eliminate the threat to Western settlement in the region.

The other major event of 1791 was the French Revolution. The Court of King Louis XVI had fallen fast in just a few short years. Heavily in debt (thanks to lending a generous amount of hard currency to the United States during the war), and unable to meet the demand of starving peasants, Paris erupted into revolution in 1789. At first, many sought to emulate the American Revolution with calls for liberty and natural rights for all citizens. Jefferson, then still minister to France, had secretly helped efforts to guide these patriotic thoughts. By 1791, the revolution was showing signs of consuming itself. But to Jefferson and other pro-French advocates, the destruction of the monarch was a welcome sight. For Washington, the scene did not feel similar to the Revolution he’d help won.

Meanwhile, Great Britain was still lurking on the outskirts of the Great Lakes. Despite agreeing in the Treaty of Paris to withdrawal all British troops from the United States, London retained some outposts just out of reach of the expanding Western Territory, buffered by the Canadian wilderness to the north. The fur trade was a serious commodity for British markets, and many saw American western expansion as a threat to it. Some in Parliament were furious that the United States had still not compensated loyalist citizens of their seized property. According to the peace deal, all former citizens could file claims in the states over lost possessions. Most claims were ignored, fueling dissent among some in the British government, and keeping the specter of harassing American interests openly. On the high seas, the British Navy began the practice of impressment, or seizing American ships and forcing their crew into service for the British. Relations between London and Paris continued to deteriorate as well.

The election of 1792 saw Washington win reelection, even as he privately expressed exhaustion and wariness taking on another term. He even had Madison draft a farewell address. His divided cabinet of Hamilton and the Federalists on one side and Jefferson and the emerging Democratic-Republican faction on the other insisted the president return for a second term. Yet Washington was unaware of how divided his cabinet had become. Jefferson, in particular, expressed a possible calamity if the president were to retire. With Washington relenting that he would stay on, Jefferson promptly tendered his resignation as Secretary of State. In truth, Washington remained in office to see to it the future capital city that would likely bare his name would be completed. Funding was a huge problem and the only reassurance that it would ever be completed was Washington’s name attached to the project. He also saw the development of several arsenals established in the eastern states.

The year 1793 proved to be one of the traumatic events for the Washington administration and the city of Philadelphia. The first came in the spring. The French government had declared war on Great Britain. Instantly, the already deep fishers in the administration split further. Hamilton and other Federalists supported British merchant trading interests and either wanted to remain neutral or declare war on France if it came to that. The Republicans saw this as a natural offspring of the American Revolution and roundly supported the declaration of war against London. Washington maintained a commitment to staying out of European affairs. He signed the Neutrality Act in April 1793 to keep the United States out of the war. The move was not popular with much of the public, despite the news the administration was receiving.

The French Revolution had turned violent, ousting the transitional government, and replacing it with what would become the Reign of Terror. The revolutionaries had also arrested the Marquis de Lafayette as a traitor, and others who tried to maintain a moderate approach. But the initial news struck American shores as celebratory. Many saw the parallels between the American Revolution having thrown off the yoke of British monarchy and the new French revolutionaries having disposed of King Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette. With Washington’s administration now divided between the pro-British Federalists (labeled Monocrats, short for monarchists, by Jefferson), and the Jefferson Democratic-Republicans who were pro-French, the streets of Philadelphia filled with citizens shouting their support for the revolutionaries. Pro-Republican newspapers sprung up labeling anyone who did not support the revolution in the vilest of terms, and even Washington himself faced the public pressure for the first time. The matter reached a new tipping point with the arrival of French diplomat Edmond Charles Genet seeking an audience with the president. Genet demanded the president’s support for the revolutionaries, but was rebuffed for his forwardness. Genet then went to the press and began attacking any American who refused to support France, including Washington. At first, Jefferson and others welcomed the embarrassment it caused to Hamiltonian-Federalists and the public rallied further around the French cause. It became dangerous at times to be a visible Federalist in the streets of American cities. But Genet overplayed his hand by insisting he would be the individual who led an inner-French uprising in the United States. Eventually, Citizen Genet was disowned by everyone.

The other major event to grip Philadelphia in 1793 was the yellow fever epidemic that would wipe out one-tenth of the city’s population. The entire federal government had to abandon the city by late summer and the sickness lingered into the late autumn. It would return again for several years, particularly in 1798, but never to the strength of its first appearance.

Lastly, Washington faced another crisis it seemed with the departure of Jefferson as his Secretary of State. Though replaced by his attorney general Edmund Randolph, the new cabinet official was no equal to the former nemesis of Hamilton. And worse for Washington, Jefferson now conducted a covert campaign of kneecapping every administrative move that he disagreed with. Using newspapers such as the Gazette and the Aurora, Jefferson pulled many strings acting as the chief propagandist, directing many attacks where the harshest criticism fell on Washington’s lap. Though never admitting to the deception, Jefferson was eventually called out by Washington in a letter in 1796 that went unanswered. The friendship would never be repaired.

The following year brought two new urgent crises that would largely define Washington’s tenure as president. The first had originated three years earlier in the backcountry of western Pennsylvania over uncollected taxes. Locals refused to pay the taxes on whiskey and an armed mob attacked the house of collector General John Neville. A former colleague and soldier under Washington, it appears the threat made on Neville set off a chain of emotions that provoked the president to act. A force of 13,000 militia was raised and Washington, along with Hamilton, traveled out to western Pennsylvania to meet Col. Henry Lee who had been given command. Washington had no intention of leading the assembled army; he only wanted to see it off before any bloodshed occurred. Fortunately, the tax evaders dispersed once the American forces approached, and Washington eventually pardoned the lone two men arrested. The show of force may have seemed excessive, but Washington, with Shays’ Rebellion still in his mind, wanted to make it clear the federal government had supreme authority. Among that authority was to collect taxes and see to it the laws were faithfully followed. Had the mobs continued to act out in a hostile matter, it threatened insurrection and the legitimacy of the government itself. Washington, remaining as president against his own wishes, knew he carried that legitimacy with whatever he did or did not do. No better situation further illustrates this than the crisis of 1794-95 that culminated in the Jay Treaty.

British policy had shifted once again in 1794. Facing a war with the French, Parliament passed the Provision Order that gave the British Navy full authority to seize any American ships at French ports or carrying French cargo. The outcry in America was swift and war fever once again broke out. Even many Federalists were quick to condemn the measures. Washington signed a temporary embargo on all trade with the British, but something more had to be done. The president proposed sending an envoy to London to smooth over tensions and work out a deal that kept the United States neutral in the European conflict. John Jay, then Chief Justice of the Supreme Court, was sent to negotiate. By year’s end, the Jay Treaty was signed, and became Washington’s most famous foreign policy initiative of his presidency. The United States had gained a few things, such as the removal of British outposts lingering on the frontier, among others. But it did not gain any compensation for lost goods on the high seas, and it did not end impressment by the British Navy of American seamen. The Jefferson-Republicans seized on the favorable terms granted to London and charged that it further showed the federal government was controlled by a pro-British faction. The treaty faced months of heated deliberations in Congress which took a major toll on Washington’s popularity. Ultimately it did pass, keeping with Washington’s long pledge for neutrality, but the next year saw him take a beating in the press that he was not accustomed to. Everything was thrown at him, including his war record and battlefield accomplishments. By the summer of 1796, George Washington was sure of one thing: he was done with being president.

Though he likely would have been elected a third time if he’d stayed on, Washington had no such thoughts by the time he started telling close friends he was stepping down. With drafts of Madison’s 1792 address, Washington leaned on his trusted friend Hamilton to write his Farewell Address, which first appeared in print in September 1796. This was Washington announcing to the world why he was stepping away from public service. He summed up his entire political career in the address, noting that he reluctantly took the position out of a sense of duty and that all of his decisions were made to uphold the republican vision of self-government under the Constitution. He also made clear how he felt about his foreign policy initiatives towards Europe. Warning that the United States should not entangle itself in foreign affairs, the address has become noted for its clarity and foreboding of how future administrations would make foreign policy decisions. George Washington would bow out of public life one last time on March 4, 1797.

After his death in December 1799, many of the age lamented what him presiding over the national affairs had meant to the young United States gaining its traction. Indeed, many were quite frank in how important his presidency had been. Noah Webster, famed for his Dictionary, wrote on February 5, 1800, “Washington, the great political cement dead.” John Jay would later add on March 29, 1811, “His administration raised the nation out of confusion into order, out of degradation and distress into reputation and prosperity. It found us withering—it left us flourishing.” Even Jefferson would write fondly of Washington’s cult of personality and ability to hold a room of wildly different opinions. Despite these postmortem reflections, it is not lost on us as Americans how vital George Washington was to the success of the young country.

As briefly demonstrated here, above everything and everyone else, it was simply Washington’s presence as the head of the government that made it succeed in its infancy. But the man was far from an empty suit or plain figurehead. Yes, the partisanship that grew in the 1790s grew under his watch. And it exploded in the elections of 1796 because of the unpopularity of the Jay Treaty. Yet Washington established precedents as the first president and made several key decisions that forever shaped the boundless success of the United States. Other decisions made during his tenure would have dire effects on the country in the following century, and those cannot be understated or overlooked either. In the opening years following the ratification of the Constitution, the country had been shaped and molded together by vastly different men of opinion. It was Washington’s opinion and leadership that carried the day and the country.

Further Reading

- George Washington’s 1791 Southern Tour: By Warren L. Bingham

- The First Congress: How James Madison, George Washington, and a Group of Extraordinary Men Invented the Government: By Fergus M. Bordewich

- His Excellency: George Washington: By Joseph J. Ellis

- The Ascent of George Washington: The Hidden Political Genius of an American Icon: By John Ferling

- Washington: The Indispensable Man: By James Thomas Flexner

- George Washington and Slavery: A Documentary Portrayal: By Fritz Hirschfeld

- The Founders on the Founders: Word Portraits from the American Revolutionary Era: By John P. Kaminski

- A Great and Good Man: George Washington in the Eyes of His Contemporaries: By John P. Kaminski and Jill Adair McCaughan

-

The Only Unavoidable Subject of Regret": George Washington, Slavery, and the Enslaved Community at Mount Vernon: By Mary V. Thompson

- An Imperfect God: George Washington, His Slaves, and the Creation of America: By Henry Wiencek