“The immense valley has thrown down upon New Orleans wealth beyond comparison, and built up a city which will be indeed to the great Father of Rivers, ‘as London to the Thames, and Paris to the Seine.’” (J.D. B. De Bow, p. 44)

In the Antebellum period, New Orleans, as American publisher De Bow noted, had many advantages. The city’s climate and soil supported the growth of numerous crops. Its connections by rail and water made it well suited for domestic and international trade. Prior to the Louisiana Purchase in 1803 and joining the United States in 1812, New Orleans had been under the rule of the Spanish and French. The city’s population increased by over 500% from 1820 to the onset of the Civil War, making it the largest Southern (and Confederate) city. Both westward expansion and an increasing population of enslaved laborers created the rising number of residents. The population increase, transportation innovation and expansion, and crop development grew New Orleans’ import and export trade into the fourth largest in the world, following London, Liverpool and New York, in terms of scale and value.

In the early 19th century, New Orleans farmers and plantation owners commonly chose rice as a cash crop. Enslaved people had shown some plantation owners the process of harvesting rice since it was a crop commonly grown in the African Senegambe region. For cultivation, rice needed five to six months of warm temperatures and freshwater swampland. Louisiana was an ideal place for rice as diseases that affected the plant were rarer in Louisiana than in other states. However, by the late-1840s, no harvesting advancements had been made for the rice plant, and as such its importance dwindled in comparison to sugar and cotton.

There is some debate about when sugarcane arrived in Louisiana, and New Orleans more specifically. Because of its proximity to the Gulf and the islands in the Caribbean, sugarcane was brought to New Orleans from Santo Domingo. Planters started cultivating it in the area sometime in the latter half of the 1700s. Enslaved people and immigrants from the Caribbean brought with them the knowledge for planting and processing sugarcane.

Growing and processing sugarcane was a laborious process. The seeds were planted in the fall and grew from grass to something similar in appearance to bamboo. Stalks reached ten to fourteen feet tall. The stalks were then harvested in the autumn the following year. The greatest innovation for sugarcane occurred in 1795 when Antoine Morin, a skilled free Black chemist working for Étienne de Boré, produced granulated sugar on the plantation. This demonstrated that sugarcane could become sugar on a plantation. After the harvest, the lifecycle included crushing the sugarcane to release its juice and repeatedly boiling the juice to transform it into cane syrup. The latter step was extremely dangerous and caused many horrible injuries for the enslaved people managing it. Finally, the syrup became granules of sugar; first brown and then white if further processed.

Sugarcane became increasingly popular to grow over time. It was another crop where losses were less likely – only frost, excessive moisture, poor soil quality or human error could harm it. While it was costly to produce, it reaped large profits for the planters. Finally, with steam power added into the processing, crop production grew. In the 1820s, the amount of sugarcane plantations had tripled, and by the late 1840s, it was the leading crop in New Orleans.

In the years leading up to the Civil War, Louisiana produced nearly all the sugar in the country. This was mostly done by five-hundred sugar plantations where two-thirds of the entire state’s slave population worked. With such demanding and varied work, many sugar plantations held anywhere from fifty to even one-hundred slaves. Sugarcane production required a variety of farming equipment, causing the sugarcane plantations in Louisiana to be the most expensive farms in the country. Even with higher operating costs, “the average Louisiana sugar plantation was valued at roughly $200,000 and yielded a 10 percent annual return.”

Cotton—not native to New Orleans—still ranked as the biggest imported and exported cash crop. Though grown in northern Louisiana, New Orleans was considered “the city of cotton” because it could be seen everywhere. During the antebellum period, more than half of all cotton grown in the country passed through the city. Most cotton went to Europe, specifically to Great Britain. In the early 1850s, New Orleans sent over 120% more cotton to Europe than Mobile, the port that had the second largest number of bales. Of the exports, Great Britian received nearly 120% more than France. Overall, cotton made up over 80% of the exported goods to foreign countries.

This monumental harvest and exportation of cotton would not have existed without the institution of slavery and the slave markets in New Orleans. From the 1830s through the Civil War, there were over fifty slave markets in New Orleans in which 750,000 slaves were sold and bought. By 1860, 7% of New Orleans’ population was enslaved, and they were held in bondage by some of the 22,000 Louisiana slave owners. The significance of slavery to the New Orleans economy can be seen in the city’s newspapers. When reading about “sugar” and “cotton,” it was not filled with economic articles, but rather advertisements for the sale of skilled slaves or notices of runaways.

Equally as important to New Orleans’ success in trade was its access to transportation and innovations made in the industry. In 1812, the first steamboat arrived in New Orleans on the Mississippi River. The creation of steamboats allowed for easier and quicker transportation of exports from New Orleans upriver. Furthermore, steamboats were able to carry more cargo, so freight rates were reduced. In 1846, 2770 steamboats brought goods to New Orleans. While there was an improvement to flatboats and other ships, steamboats still had some issues. Their ability to travel the river depended upon whether the water was high or low; during a drought, trade could be significantly affected. Railroads offered a more reliable method of transportation to and from New Orleans; these were built out in the 1830s. Railroad expansion also improved New Orleans’ access to other regions and decreased the transportation time for goods. The network of railroads, the Mississippi River, and proximity to the Gulf made New Orleans a prime center for trade.

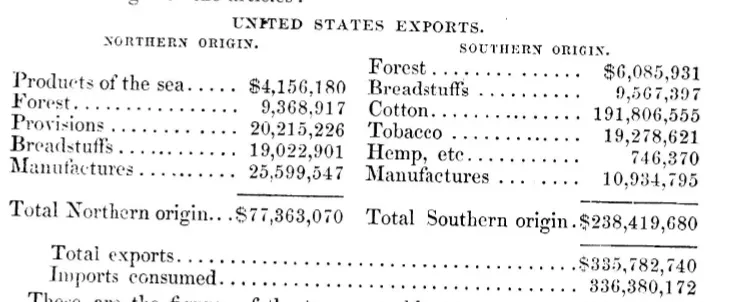

New Orleans slavery, crops and exports were threatened with the Civil War. In 1860 on the eve of that conflict, nearly $110 million worth of cotton passed through New Orleans. With cotton being a Southern crop and “king” in the foreign markets, it was especially important to the Confederacy, its economy and its war effort. For example, cotton was exchanged for army supplies. When the Union implemented its blockade on Confederate ports, it eventually stopped most imports and exports; the trading situation became especially dire when the Union overtook the Mississippi as well. In 1862, De Bow’s Review, a magazine examining “Agricultural, commercial, industrial progress and resources” published the following table:

It recognized that “Three-fourths of the national exports are embargoed by blockade. It is very important thoroughly to understand that fact, because on it hangs all the finance of the war.” Because of cotton’s worth, and the fear of the excess supply falling into Union hands, the Confederates began to transfer the cotton west of the Mississippi River. If they were unable to do that, they burned bales of cotton.

Following the conclusion of the Civil War, New Orleans particularly struggled to rebuild. Due to its reliance on slavery to cultivate its main crops and exports, the economy was significantly affected and the state changed.

Sources:

"New Orleans and Charleston [pp. 44-51]." In the digital collection Making of America Journal Articles. https://name.umdl.umich.edu/acg1336.1-01.001. University of Michigan Library Digital Collections. Accessed May 14, 2025.