Steamboats and the Mississippi River

The Mississippi River runs from northern Minnesota down through Louisiana to the Gulf. Spanning almost the entirety of the United States north to south, it is 2350 miles in length. Its name, which comes from the Native American Ojibwe language, means Big or Great River. As Americans moved westward in search of opportunity, land, and jobs, they settled along the Mississippi River. The Mississippi allowed farmers to move their produce and other goods down river to port cities like New Orleans. Prior to the 1810s, flatboats and keelboats, which averaged twenty miles per day, were the only mode of river transport available. “Rivermen” on these boats traveled hundreds or thousands of miles, depending on their destination, and upon arrival distributed the goods, sold the flatboat for lumber, and walked back home. Some rivermen’s journey home lasted for up to four months. The laborious and timely aspects of river trade were forever altered with the invention of the steamboat. This revolution in transportation led to easier trade and movement around the western part of the country, new jobs, and better means of communication.

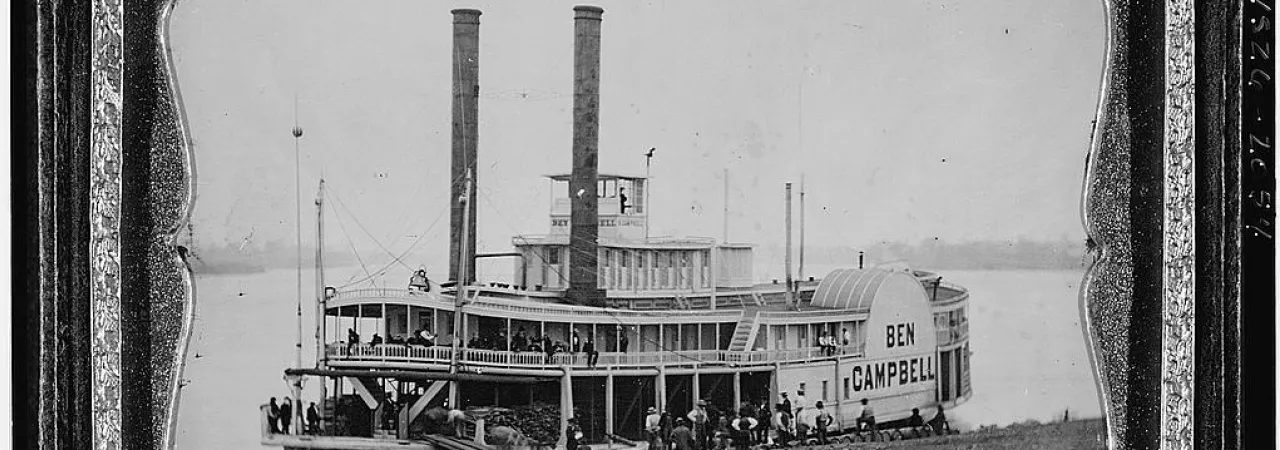

Robert Fulton created the first steamboat to travel down the Mississippi River. Named “New Orleans,” it departed from Pittsburgh for New Orleans via the Ohio and Mississippi Rivers, arriving in January 1812. Compared to flatboats and keelboats, steamboats could travel an average of fifty miles per day (in the 1810s) and one hundred miles per day (in the 1820s) due to their form allowing nimble navigation and power. Steamboats were narrow and had a shallow flat bottom, requiring a mere three feet of water to float. Their power came from paddle wheels moved by high-pressure steam engines. Because of their swiftness and capacity to move substantial amounts of cargo quickly, steamboats rapidly became a popular means of transport. In 1814, New Orleans recorded 21 steamboat arrivals, while in 1846, the city recorded 2770 steamboat arrivals and was the fourth busiest commercial port in the world. The increased use of steamboats led to many developments along the river.

Steamboats provided much easier and affordable movement for people. Numerous historians attribute the rapid growth of communities along the river to steamboats because it made travel to unsettled western territory easier. For example, from 1800 to 1860, the Mississippi white population grew from 5,179 to 353,901; the enslaved population also grew drastically. Likewise, the population of the city of New Orleans increased from 17,242 to 116,375 between 1810 to 1850.

Beyond moving and resettling in new places, steamboats made personal travel easier. Three types of steamboat services were offered. The “Transient” was an ad-hoc freelance operation with no fixed schedule; this was often cheapest for passengers. The “Packet” and “Line” services made regularly scheduled trips, departing and arriving at specified dates and times. Passenger fare was based on whether travel was upriver or downriver as well as ticket type. Cabin passengers received an experience similar to a hotel, while deck passengers were situated among the cargo. Regardless, the experience was quicker and more comfortable than any travel before.

Though labor was no longer needed to move the boat, steamboats created numerous job opportunities. Depending on the boat’s size, they could require anywhere from five crew members to several dozen. The officers were typically white American men with the crew being made up of immigrants, slaves and freed people. These men kept the boilers running, loaded and unloaded cargo, cleaned the boat and served the passengers. Some steamboats had restaurants and lounges with star chefs and orchestras aboard. On land, steamboats required operations management, construction, insurance, supplying, repairs and refueling. Often steamboats were constructed along the Ohio River. Repair and refueling stations were located along the river at various landings, bolstering river port city and town economies.

In addition to creating jobs, steamboats drastically changed trade along the river. Before their invention, farmers in the West had few options to transport their produce aside from floating it down river on flatboats or keelboats, which were small and slow. Steamboats, on the other hand, transported fresh produce quickly, cheaply and in massive quantities. Rates for shipments continually changed based on the cargo offering, supply of tonnage, and depth of water. A 450-ton steamboat could carry around 280 tons of goods, hundreds of bales of cotton and around 100 passengers. For ease, plantations were often located near steamboat landings. As the use of steamboats increased, so did the output of cotton. Between 1820 and 1860, Mississippi cotton production went from twenty million pounds to 535 million pounds; the most in the country. On Tuesday, November 15, 1859, the New Orleans Crescent reported that over 4,500 bales of cotton arrived via steamboat from Vicksburg; during the Antebellum period, over half of all U.S. cotton passed through New Orleans. Beyond cotton, livestock, flour, grain, pork, timber, corn, sugar, tobacco, and molasses were the main products transported downriver. In exchange, manufactured and processed items were brought upriver such as glassware, soap, textiles and candles. Some planters found such value in steamboats that they bought one or invested in one to help facilitate the trade of their goods.

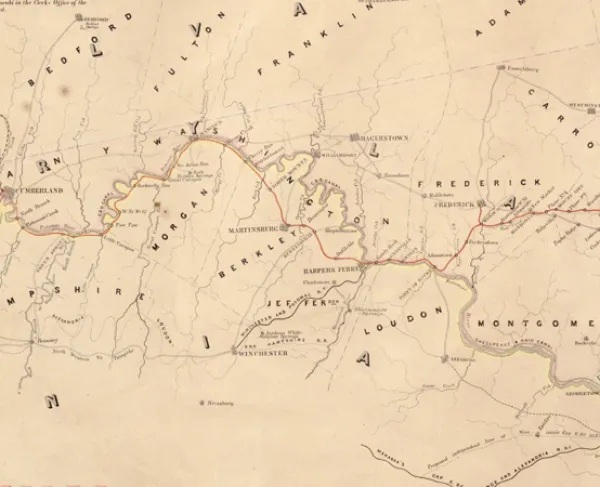

Steamboats also improved the means of communication for people in the West. They established a quick means of relaying information throughout the Mississippi Valley. Mail routes and contracts were established which operated on a regular schedule. Newspapers, letters and other forms of communication were delivered along these routes. Mail Route No. 5711 operated between New Orleans and Vicksburg daily for ten months of the year and provided “the only regular connection that the interior of Louisiana and Mississippi can have with New Orleans and the South.”

Despite the better communication, faster travel, and increased trade, steamboats had disadvantages as well. On any journey, a steamboat could become stuck on a sandbar, encounter fog or storms, catch on fire, snag, or collide with something in the water and experience boiler explosions. All were serious disasters and could not only cause unreliability and delays, but also injuries or even death. It is estimated that over 4,000 people died due to steamboat crashes on the Mississippi during the antebellum period. Nevertheless, steamboats remained a key mode of transportation for passengers and goods in the West until the improvement of rail networks and services in the area occurred in the 1850s.

Suggested Readings:

- Steamboats on the Western Rivers: An Economic and Technological History by Louis C. Hunter (Harvard University Press, 1949)

- The Western River Steamboat by Adam I. Kane (Texas A&M University Press, 2004)

- The Transportation Revolution, 1815-1860 by George Rogers Taylor (Harper Torchbooks, 1951)