Magna Carta, Facts, Myths, and Legacies

The principles and ideologies upon which the American Revolution stood did not spring up fully formed upon the signing of the Declaration of Independence in July of 1776, but instead grew out of roots that stretched back for centuries of English history. Even at that point, concepts like democracy and republicanism were well over a thousand years old, and as educated individuals, most of the Founding Fathers were greatly familiar with the histories of Democratic Athens, the Roman Republic and several other ancient experiments in representative government. But though these examples exerted influence over the eventual structure of the United States government, the prime political theory motivating the revolution, that of individual rights and liberties, was more intertwined in a narrative of English history that begins over five hundred years prior, with a different rebellion, and the signing of a different famous document.

In 1215, King John of England faced several crises all compounded on top of one another. His elder brother and predecessor Richard the Lionheart had used England primarily as a piggy bank to finance his crusading in the Levant as well as his territorial conflicts in continental Europe. After Richard fell in battle in 1199, John inherited his massive debts which were difficult enough to pay off through the wealth generated in both England and his extensive territories on the continent, but soon into his reign, John only contributed further to this financial crisis as he tried unsuccessfully to defend his French territories from a resurgent France under King Philip II, placing even more of the burden on John’s English barons. To make matters worse, though administratively competent, John utterly lacked his brother’s and father’s charisma, gaining a reputation for pettiness and cruelty that led to him quarreling with not only his vassals but also the Church over the issue of appointing bishops within England, leading to his temporary ex-communication by Pope Innocent III in 1209, a matter only resolved when John begged Innocent for forgiveness and swore fealty to him as a vassal of the Papacy. As elsewhere in Medieval Europe, members of the English landowning class understood relations with their monarch to be one of reciprocity. In exchange for doing him homage and swearing to give him their loyalty and counsel, they expected the sovereign to grant them counsel and loyalty in return, usually in the form of certain favors, just as they did with their own sworn vassals. When John not only failed to live up to these expectations, such as appointing commoners to government office instead of more aristocratic candidates and heavily punishing those who refused to pay their taxes, coupled with his loss of legitimacy in military and spiritual matters, the barons decided they’d had enough and staged a revolt in 1215 against the King’s capricious government, seizing the city of London and forcing John to take refuge at Windsor Castle.

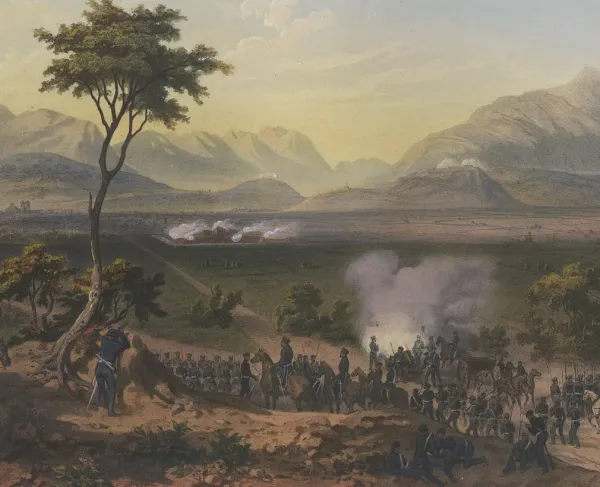

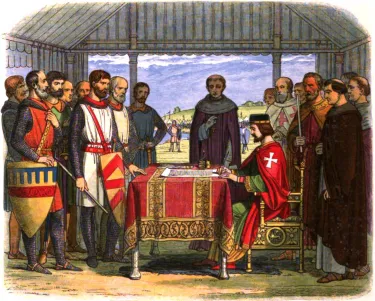

By the time the rebels arrived at Windsor, John had not yet had enough time to gather his loyalist forces, and so agreed to truce negotiations with the barons at a nearby meadow called Runnymede, mediated by Stephen Langton, Archbishop of Canterbury. They called the peace treaty they negotiated there Magna Carta Liberatum, Latin for “Great Charter of Liberties,” and it was hailed as such by many later figures like Thomas Jefferson. But we must make some important points here. The document, often referred to simply as Magna Carta, did indeed innumerate several various rights and liberties, as well as limitations on the King’s powers over his vassals, but when looking at the text of the document today, a modern reader might be confused at some of its content. Magna Carta does not proclaim any idea of universal human rights, as some of the texts that claim it as inspiration do. Though it states that it grants liberties “To all Free Men of Our Kingdom...for us and our heirs forever,” this referred almost exclusively to the feudal land-owning aristocracy, whereas the overwhelming majority of people living in England were unfree serfs bound to the land where they lived and in service to said landowners. Therefore, most of the clauses in Magna Carta deal with issues central to their concerns, such as the inheritance of land, the regulation of debts, and formally encoding the rights and privileges enjoyed by the aristocracy. Now, there are four clauses from the 1215 original document that still remain in effect as United Kingdom law, mainly referring to the freedom of the English Church, the “ancient liberties and free customs” of the City of London, and the right to due process that was later expanded to all citizens rather than just a minority, and no document before it had encapsulated the power-sharing nature of feudal politics into a written agreement, but if we argue that Magna Carta was the first step towards the representative and pluralistic government, then it was a very small step indeed. In addition, the 1215 agreement ultimately failed even at its original purpose, a peace treaty between King John and his barons. Almost immediately after attaching his royal seal, John convinced Pope Innocent of annulling Magna Carta and threatened to excommunicate anyone who tried to enforce it. Outraged, though not entirely surprised, the barons responded by marshaling their forces and inviting Prince Louis of France to claim the English throne for himself, while John gathered his remaining supporters and bolstered them with foreign mercenaries, sparking the First Barons’ War. John’s loyalist army under the famous knight William Marshall ultimately crushed baronial and French forces at the Battle of Lincoln in 1217 and ended Louis’ hopes of inheriting both the English and French crowns, but John’s death and ascension of his nine-year-old son Henry III to the throne proved a godsend to the ultimate survival of Magna Carta. As Henry’s regent, Marshall convinced the boy king to reissue the charter as a token of magnanimity to the defeated rebels, and though conflicts between the crown and nobility continued to erupt, Magna Carta continued to be reissued multiple times throughout the Middle Ages, until such an event became almost routine.

It was not until the 17th century that the myth of Magna Carta, which arguably had an even greater impact on the American Revolution, began to take hold, thanks largely to the writings of jurist Edward Coke, who wrote mostly in the decades leading up to the English Civil War (1642-1651) between the Royalist army of King Charles I and the supporters of Parliament. During this period, the decentralized nature of medieval feudalism in Europe had broken down, replaced in many cases by powerful centralized states headed by absolute monarchs, justified by a political theory which stated that a king was divinely appointed by God to rule, and therefore should be held accountable by no other men and no laws often called the Divine Right of Kings. This system of absolutism is often surmised by a statement from King Louis XIV of France, “L’État, c’est moi,” or “The state, it is I.” Proponents of Absolutism in England included none other than King James I and his son, King Charles I, which ideological opponents like Coke saw as severe threats to the authority of Parliament, the advisory body that had grown into something of a real counterweight to the king’s authority, as well as the rights of individual citizens, but in order to make his case, Coke needed a precedent to match Absolutism’s Biblically-inspired legitimacy. He settled on Magna Carta as his example of Universal Law, that which stood as a higher authority than both King and Parliament and going so far as to say that it also hearkened back to even more ancient liberties dating to the time of the Anglo-Saxons (whereas the vast majority of the men present at Runnymeade spoke Norman French rather than English). Many of Coke’s contemporaries, as well as modern historians, have correctly labeled his arguments as anachronistic, but this new perception of Magna Carta as a guarantor of civil liberties quickly took hold in the popular imagination. Coke’s rhetorical use of Magna Carta also helped him pass his own legislative masterwork, the 1628 Petition of Right, aimed at halting King Charles’ unaccountable behavior and unpopular policies by affirming the freedom from taxation not approved by Parliament, as well as reaffirming the freedoms from detention and imprisonment without charge or trial, also called Habeus Corpus, but now, these freedoms were extended to all English subjects.

Coke did not end England’s struggle against Absolutism within his lifetime, but his works continued to influence future generations as the 17th century continued to mark England with civil war, rebellion, and revolution in the name of preserving the constitutional character of England’s government. Following the Glorious Revolution of 1688, which overthrew the absolutist Catholic monarch James II in favor of the more constitutionally-minded couple William and Mary, Parliament took yet another step to ensure the protection of English individual rights with the passing of the 1689 Bill of Rights, which still remain in effect in all British Commonwealth. Like the United States' own later Bill of Rights, the bill protected the freedom of speech, the right to bear arms, and protection from cruel and unusual punishment. The most notable provision missing is any protection for freedom of religion, as all of these rights were extended only to Protestants. But the legacy of Coke’s rhetorical appropriation of Magna Carta did not just hold sway in Europe. This new perception proved especially popular in the fledgling English colonies in North America, where settlers chartered their new local governments (some of which, such as Virginia, Coke himself had a hand in writing) based on the principles laid out by Coke in his writings.

The men who came together in Philadelphia to sign the Declaration of Independence in 1776 were practically marinated in this English political tradition of the primacy of the Rule of Law and respect for individual liberties. Despite the artificial origins Coke created, it was a primary force in shaping the Founding Fathers’ view of their own rights and in pushing them to rebel against King George and Parliament.

Further Reading

- King John And the Road to Magna Carta By: Stephen Church

- 1215: The Year of Magna Carta By: Danny Danziger and John Gillingham